Ahead of the return to London of arguably his greatest work, Glengarry Glen Ross, Charlie Connelly considers the craft of polymath and playwright David Mamet.

In the mid-1960s Carol Stoll would sit smoking at the cash register in the window of the Oak Street Book Shop in Chicago and watch a teenage David Mamet saunter up the street, open the door with a tinkle of the bell, nod a greeting and walk to a small room at the back of the shop where the plays were kept. There he would pull out a Grove Press edition of Samuel Beckett or Harold Pinter and settle down to read.

Stoll was used to young actors and playwrights using the shop as a library – the Esquire Theater was two doors along the street – and she was happy to indulge them; suggesting books, even assigning coffee mugs to her favourite regulars which were kept behind the counter.

It was there, immersing himself in Beckett and Pinter under Stott’s indulgent eye, that Mamet received arguably the most important part of his theatrical education. ‘This was my first exposure to drama as literature,’ he would later recall, ‘drama as a living expression of things that people felt. It was kind of a revelation.’

That Pinter and Beckett would open up a world of possibility for Mamet was no surprise, having grown up in Chicago with a labour union lawyer father with a short temper, and who was a stickler for verbal accuracy and economy.

‘From the earliest age, one had to think, be careful about what one was going to say, and also how the other person was going to respond,’ recalled Mamet.

His mother would frequently demand, ‘Oh David, why must you dramatise everything?’ She didn’t intend it as a compliment, let alone career advice.

Discovering Beckett and Pinter, not to mention Chekhov, and studying their every line and nuance in the silence of a Chicago bookshop was a profoundly formative experience for Mamet, who learned how to strip down the mechanics of play writing and retain only what was absolutely necessary.

‘Chekov removed the plot,’ he’d say, ‘Pinter removed the history and narrative, Beckett the characterisation.’

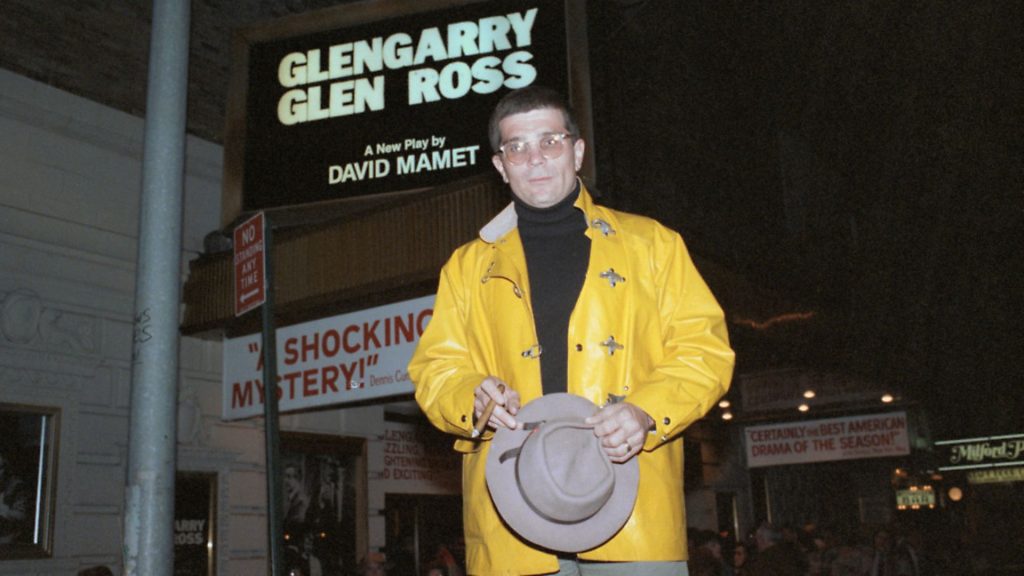

In 1983, with a string of theatrical successes already behind him, there emerged arguably the finest distillation of everything he’d learned.

Glengarry Glen Ross, which opens at London’s Playhouse Theatre on October 26 with a cast including Christian Slater, Kris Marshall and Don Warrington, follows a group of increasingly desperate Chicago real estate agents as they try to shift some unspectacular property by fair means or foul in order to win a Cadillac and, more importantly, avoid being fired.

This hard-bitten, survival-of-the-fittest narrative earned Mamet a Pulitzer Prize, a Tony and an Olivier Award, while his screenplay for the film adaptation that starred Jack Lemmon and Al Pacino was nominated for an Academy Award.

The fact that Mamet’s most famous work should be revived with a London run, not to mention one that straddles the writer’s 70th birthday at the end of November, is wholly appropriate. As while the play itself is steeped in Mametian Chicago, London played a crucial role in its birth.

When he wasn’t holed up in the Oak Street Book Shop Mamet was working a string of jobs to support himself until he could make a living from writing, including one as an office assistant at a real estate company that he stuck at for a year. As the months passed he found himself growing in admiration for the fast-talking hard-sellers with whom he shared an office.

‘Those guys could sell cancer,’ he said. ‘They were amazing, a force of nature. These men had spent their whole life in sales, always working for a commission, never working for a salary, dependent for their living on their wits and their charm.’

By the time he wrote the play in the early 1980s Mamet had honed a terse, almost minimalist style in a prolific output of works such as The Duck Variations, Sexual Perversity in Chicago and American Buffalo. There are few actors in a David Mamet play, next to no stage directions and he prefers his sets to contain the bare minimum of props.

‘I always thought that the trick was to be able to do it on a bare stage, with nothing but one or two actors,’ he said. ‘If one could do it like that, then one has done something to keep the audience’s attention, make it pay off over an hour and a half.’

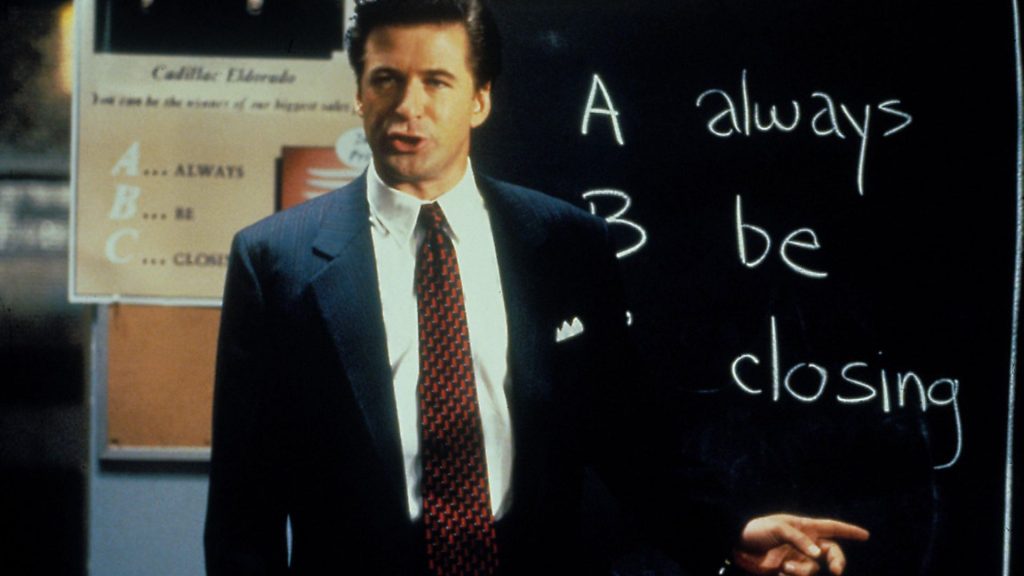

The true essence of Mamet’s craft lies in his dialogue, which has a staccato, everyday feel, far closer to the language of the street than the language of the stage. That’s not to say it’s simplistic: every word has been honed and shaped to fit a sentence, a rhythm, a character and a scene. There’s not a spare syllable in a Mamet script and his plays are almost as much about what is left unsaid than what is. It’s a craft that even has its own name: Mametese.

Glengarry Glen Ross represents the apotheosis of Mametese. Blunt, uncompromising and frequently peppered with swearwords, its vivid vernacular is about as far from the traditional view of American theatrical culture as you could find.

Indeed, a joke popular during the 1980s ran: a down-and-out approaches a smartly-dressed man in a suit and asks for money. The man refuses, saying, ‘Neither a borrower or a lender be. That’s William Shakespeare.’ The down-and-out replies, ‘Go fuck yourself. David Mamet’.

Mamet had found writing Glengarry Glen Ross more of a struggle than usual. Still unsure, he sent it to Harold Pinter and asked him what the script lacked. Pinter read it, loved it, and forwarded it straight to Peter Hall at the National Theatre in London, who immediately arranged for it to be staged at the Cottesloe in the autumn of 1983. The following year Glengarry Glen Ross won the Pulitzer.

‘Pinter was always a hero of mine who was responsible to a large extent for me starting to write,’ said Mamet, who often cites the plays such as A Night Out and The Birthday Party that he read cross-legged on the floor of a Chicago bookshop as key influences. ‘He was my first encounter with modern drama. His work sounded real to me in a way that no drama ever had. It was stuff you heard in the street. It was the stuff you overheard in the taxicab. It wasn’t writerly.’

Through Pinter, Mamet learned the power of the pause and its ability to engage the audience with the spaces in between as much as the words spoken by the actors.

In 1993, the British playwright directed the first British production of Mamet’s controversial Oleanna at the Royal Court in London, the story of a professor accused by a student of sexual exploitation. Scattering the play with even more pauses than those written by Mamet, Pinter’s production ran for a full half-hour longer than usual.

Hero he may have been to Mamet but Pinter’s decision to reinstate the ending of an earlier draft of Oleanna caused a rift between the two writers.

‘There can be no tougher or more unflinching play than Oleanna,’ wrote Pinter in a letter to Mamet explaining his decision. ‘The original ending is, brilliantly, ‘the last twist of the knife’. The last line seems to me the perfect summation of the play. It’s dramatic ice.’

The rift was healed by the end of the decade when Pinter, Mamet and Mamet’s other major influence Samuel Beckett all combined for a production of Beckett’s Catastrophe.

Part of a project staged around the turn of the millennium to film all of Beckett’s plays, Mamet’s Catastrophe featured Pinter playing a brusque theatrical director (who, perhaps in a wry nod to the Oleanna incident, sweeps in, changes everything about a production and sweeps out again), Mamet’s wife Rebecca Pidgeon as the put-upon assistant and Sir John Gielgud, just a few weeks before his death, as the actor dehumanised by Pinter’s vision of performance.

Beckett wrote Catastrophe in 1982 and dedicated it to Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright who would eventually become President of the Czech Republic. At the end of the play the actor, whose face remains invisible as the director and assistant speak and behave as if he’s merely a mannequin, defies instruction and looks up into the spotlight in a bold statement about the repression of humanity and creativity.

Filmed at Wilton’s Music Hall in the East End of London, the play runs for a shade under six minutes, bringing together in that short time all the Beckettian and Pinteresque influences that shaped Mamet as a writer and director in the first place.

Aside from Pinter himself, in fur coat strutting up and down the stalls barking orders, there are the characteristic silences, not least from Gielgud who never utters a word, lurking motionless at the edge or in the background of the shot until the starkly-lit close-up finale of his steely, watery eye rising into the spotlight in a bold and brave affirmation of his humanity.

Beckett’s economy of dialogue provides the conduit to Mamet’s production here too, and it’s clear the director is immersed in his hero’s terse lines.

‘He blew the top of it off,’ said Mamet. ‘Beckett was kind of a demigod to me.’

Indeed at one point the director character, responding to a suggestion from his assistant, explodes, ‘For God’s sake! This craze for explication! Every ‘i’ dotted to death!’ could stand alone as a summary of all three men’s approach to writing drama. Even the choice of venue feels significant: a Victorian music hall, a place built on raucous, demanding audiences with little tolerance for the indulgent or the phoney. It was almost a nod to Mamet’s early years in Chicago, of which he said, ‘People went to the theatre just like they went to the ball game: they wanted to see a show. If it was a drama it had to be dramatic and if it was a comedy it had to funny, period. If it was those things they’d come back. If it wasn’t those things, they wouldn’t come back’.

It’s a philosophy that has served him well, not least in his forays into other outlets, especially cinema. As well as Glengarry Glen Ross, Mamet has enjoyed considerable success as a screenwriter and director.

His adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice in 1981 received wide plaudits, while his directorial debut House of Games, for which he also wrote the screenplay, won Best Film and Best Screenplay at the Venice Film Festival in 1987. Add in his screenplays for The Untouchables and Hannibal, to name just two and it’s clear Mamet’s talents extend way beyond the stage.

There have been novels, books of essays and even children’s stories: a quick tot-up lists 36 plays, 29 screenplays, 17 books and 11 film directing credits, an extraordinary legacy of polymathy by one of the most prolific writers of any generation. He even wrote an episode of Hill Street Blues.

While there have been few indications of his powers waning as he approaches 70, Mamet did raise a few eyebrows in 2008 when he announced in a newspaper article he was no longer a ‘braindead liberal’ and embraced conservative thinkers and thinking.

A book followed in 2011, The Secret Knowledge: On The Dismantling of American Culture that seemed the antithesis of everything that had gone before, brimming with rambling, unsupported generalisations that sounded more barstool ideologue than one of the most incisive minds of the modern era.

Mamet was in the news again this summer when it emerged licences for performing his plays were being issued only with the caveat that there be no post-show debates, talks or Q&A sessions within two hours of the performance on pain of a $25,000 fine. Many theatrical hands flew to cheeks at the news, but it’s an affirmation of what Mamet has always tried to achieve, even with The Secret Knowledge: making the audience think for themselves. ‘For me, to talk to the audience is like the audience wanting to know how a magician does the trick,’ he once said in an interview. ‘The magician can’t tell them because if he does it ruins the trick.’

It’s something he learned sitting in the Oak Street Book Shop, losing himself in Beckett and Pinter.

There were no discussions there, no panels of experts and blowhards among the shelves, just the words and their effect on the imagination of one of the modern era’s most extraordinary writers.

In the online masterclass in dramatic writing he unveiled earlier this summer Mamet reveals arguably the key to his success and longevity, characteristically in just five words.

‘One rule,’ he says. ‘Don’t be boring.’

• MAMET IN HIS OWN WORDS

There’s nothing in the world more silent than the telephone the morning after everybody pans your play. It won’t ring from room service; your mother won’t be calling you. If the phone has not rung by 8 in the morning, you’re dead.

Here’s what happens in a play. You get involved in a situation where something is unbalanced. If nothing’s unbalanced, there’s no reason to have a play. If Hamlet comes home from school and his dad’s not dead and asks him if he’s had a good time, it’s boring.

I like mass entertainment. I’ve written mass entertainment. But it’s the opposite of art because the job of mass entertainment is to cajole, seduce and flatter consumers to let them know that what they thought was right is right, and that their tastes and their immediate gratification are of the utmost concern of the purveyor. The job of the artist, on the other hand, is to say, wait a second, to the contrary, everything that we have thought is wrong. Let’s re-examine it.

The main question in drama, the way I was taught, is always what does the protagonist want? That’s what drama is. It comes down to that. It’s not about theme, it’s not about ideas, it’s not about setting, but what the protagonist wants.

A stage play is basically a form of uber-schizophrenia. You split yourself into two minds—one being the protagonist and the other being the antagonist. The playwright also splits himself into two other minds: the mind of the writer and the mind of the audience. The question is, how do you lure the audience in, so they use their reasoning power to jump to their own conclusion so that at the end of the play, as Aristotle said, they’re surprised?

I’ve been making a living writing for close to 50 years and I’ve never met a stupid audience.

It’s not the actor’s job to embellish the play but to do something more worthwhile and difficult: to resist embellishing it. It’s when one resists the impulse to help that the truth emerges. The great actors I’ve seen in movies or on stage are capable of being quite still, and letting their uncertainty, fear and conflicting desires emerge rather than trying to cover them up with their ideas.

(Jean-Luc) Godard said every movie has to have a beginning, middle and end but not necessarily in that order. And that’s why French movies are so boring.

A movie is a juxtaposition of images. We don’t need dialogue in a movie. Never. How do we know? Because when we’re on the airplane we’re looking across at the other guy in the next seat watching a movie and we get fascinated. We can’t hear the dialogue, so what good is dialogue? Not very much good at all.

The first time I met Tennessee Williams he showed up at a party in Chicago with two beautiful young boys who were obviously rough trade. He looked at them and then he looked at me and he said, ‘Expensive habit’. So that’s kind of how I feel about liberalism. It’s a damned expensive habit.

My idea of perfect happiness is a healthy family, peace between nations and all the critics die.

Somebody said that the reason that we all have a school dream – I’ve forgotten to do my paper! I’ve forgotten to study! – is that it’s the first time that the child runs up against the expectations of the world: the world has expectations of me and I’m going to have to meet them or starve, meet them or die. And I’m unprepared.

We live in an illiterate country. The mass media – the commercial theatre included – pander to the low and the lowest of the low in human experience. They, finally, debase us through the sheer weight of their mindlessness.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37