After years under a brutal dictatorship, Uzbekistan is trying to open up to the world. GARTH CARTWRIGHT went there to find out how it is going.

A vast, landlocked desert at the heart of the Silk Road, Uzbekistan’s aura of exoticism and brutality has enchanted and repelled Anglo minds across the centuries.

Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine The Great, Parts I and II ensured the 14th century Uzbek warlord would forever be known in the West as a terrifying despot. In the 19th century these arid lands gained a degree of intrigue as Britain and Russia engaged in the Great Game, both attempting to wrestle the Uzbeks into their empires.

James Elroy Flecker’s poem The Golden Road To Samarkand scored with Edwardian readers, while Jimi Hendrix’s death at Hotel Samarkand (in Notting Hill Gate) reinforced the Mystic East connotations hippies harboured about the region. The destruction of the Aral Sea (shared by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan) due to intensive cotton farming in the 1980s demonstrated the callous behaviour of Soviet politicians and their servile apparatchiks towards Central Asia.

Craig Murray, the British ambassador to Uzbekistan, upset both Tony Blair and George W. Bush’s governments when he insisted on speaking out about the appalling human rights record of president, Islam Karimov. Murray lost his job but considerably raised Uzbekistan’s profile – his heated allegations on how Karimov had political prisoners tortured then boiled alive (alongside many other nefarious activities – including narco-state activities) was not what Blair-Bush wanted publicised about an ‘ally’ in the War on Terror.

In 2005 Karimov ordered the massacre of several hundred peaceful protesters in the south eastern city of Andijan. This provoked Western governments to complain. Karimov responded by declaring the protestors were Islamists (a lie), then ordering the closure of the US air base in Karshi-Khanabad. He also set about improving ties with China and Russia – both of whom supported the regime’s response in Andijan. Not a nation welcoming Western visitors then. Except Uzbekistan now is.

Since February this year, travellers from more than 50 nations – including the UK – no longer need visas to visit Uzbekistan. Karimov’s death in 2016 saw his prime minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev become president and, in true Khrushchev-style, he has set about thawing relations with the wider world. Removing visas for independent travellers – and exit visas for Uzbeks who wish to travel abroad – are part of a package of reforms Mirziyoyev has embarked upon. The changes encouraged me to take a trip there in late April.

As luck would have it we landed in a bitterly cold and wet Samarkand. For an ancient city with a mythic reputation, Samarkand resembles many other post-Soviet settlements: wide boulevards, neat parks, ugly buildings. Statues of Lenin have been replaced with statues of Amir Timur (or Marlowe’s Tamburlaine), the warlord now being hailed as Uzbekistan’s founder.

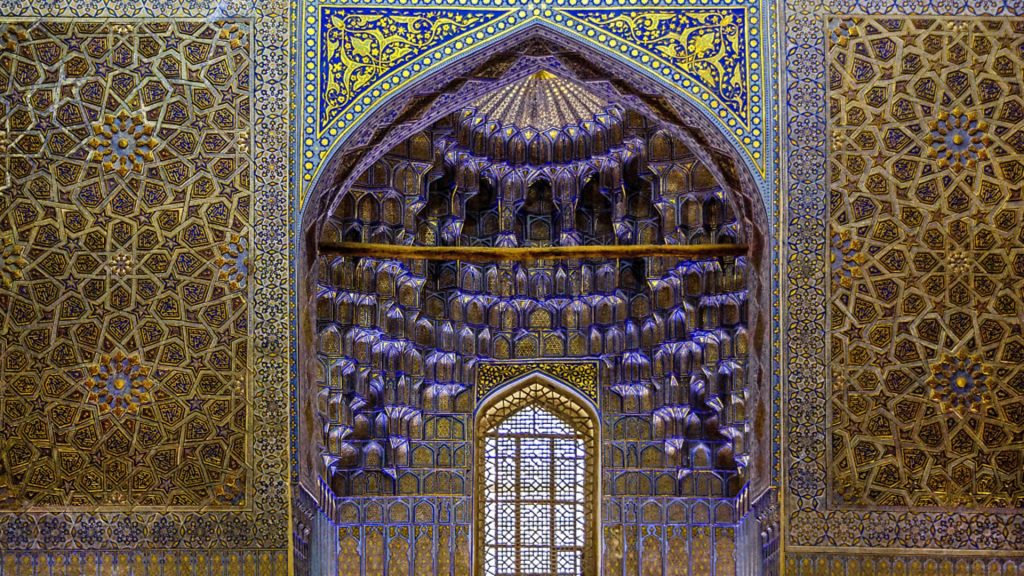

At the city’s historic heart is Registan, a gathering of three madrassas from the 14th to the 16th century when the Silk Road enjoyed its most glorious epoch. These huge structures, beautifully decorated with ceramic tiles, were once where the best and brightest came to study, an Islamic Oxford of sorts. Now all three exist as monuments from a bygone age for both western and eastern tourists – on a damp afternoon the pilgrims far outnumber the European visitors: Uzbekistan is home to some of the holiest sites in Islam and the relaxation of visas has encouraged large numbers from Turkey, neighbouring states and other Muslim nations to visit.

While nominally secular, the Uzbek government is spending large sums re-opening mosques and madrassas that were closed or neglected during the Soviet era: Emphasising a commitment to Islam pulls in the pilgrims while acting as a pressure valve in a nation with a large peasant population.

Paradoxically, the tomb of Islam Karimov (in Samarkand) is now treated as a shrine by some Uzbeks who, when we visited, came to pray, kiss the tomb and take selfies. Stalinist tyrant as Father of the Nation? Some believe so. There’s even a strict dress code (no shorts on men, no short dresses for women, no uncovered shoulders for either sex) here that’s absent from Registan.

A rapid transit train line took us to Bukhara, a historic city that lacks Samarkand’s mythic status but is far more enchanting – thus its pedestrianised centre is jostling with tourists. A huge amount of building is under way here and many a historic mosque and madrassa appears to have been refitted with new brick and tile work.

Stalin designated that Bukhara serve as the centre for Central Asian Islam; its huge Kalyan Mosque, magnificent minaret and madrassa were allowed to operate when most religious institutions were forcibly closed. Today they continue to do so, ensuring the city remains a hub for Sufism.

Bukhara is also home to a functioning synagogue – Uzbekistan was, until the collapse of the Soviet Union, home to a sizeable Jewish populace. Today few remain and Bukhara’s Jewish quarter is now almost entirely transformed into luxury guesthouses, but the synagogue remains open as a testament to tolerance and diversity.

Central Bukhara is akin to visiting tourist towns in Turkey – hawkers speak several languages while attempting to entice visitors into shops full of carpets, jewellery and ceramics. Tourism is so new the Uzbeks are not yet cynical in their greetings: right now everything feels fresh and Bukhara’s architectural beauty, ranking alongside Isfahan in Iran as the Islamic Florence, ensures many more will come to visit.

A six-hour taxi ride north took us to Khiva, a city whose old town resembles the kind of frontier settlement the likes of Star Wars and Game of Thrones employ as sets. Surrounded by 10-metre high mud brick walls – the houses and buildings behind these walls are almost entirely built from the same materials – Khiva is a dusty spectacle.

Turkmenistan’s border is nearby and one senses just how harsh these lands once were; Khiva being home to the Silk Road’s most lucrative slave market until the mid-1800s (when Anglo-Russian cooperation forced its closure). Back then a Russian male fetched the highest price. Today a more secretive mode of slavery seemingly continues to exist in Uzbekistan: Considerable numbers of peasant children and adults are forced to pick cotton come harvest time.

Not that Khiva needs slaves today: it is packed with tourists. So much so the authorities are considering making entry to the old town by ticket only. I’m unsure what has made Khiva suddenly so popular – especially with young Japanese women – but this isolated, unrefined city’s old town is already filling close to capacity. Not that the Uzbek authorities have given a great deal of thought to what tourists experience here (beyond the wild ambience): An £18 ticket guarantees entry into all historic structures, yet most operate as inept ‘museums’, the few photos and ornaments detailed only in Uzbek (with the occasional Russian translation).

Further north to Nukus found us entering what was, during the Soviet Union, a closed city: Nukus being where chemical weapons were created (including Novichok, which was used in the poisonings of Sergei and Yulia Skirpal in Salisbury last year). Today it is a boom town as a result of the huge deposits of natural gas and oil that have been discovered recently in the surrounding desert. These, combined with large resources of gold and uranium, have ensured Uzbekistan now has one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Nukus has a vivid, sprawling outdoor market – Uzbek markets are predominantly food oriented but pretty much everything the household needs is available – and the Savitsky Collection, a vast marble museum complex based around the collection of the late Igor Savitsky (1915-84). He was a Russian anthropologist and Sunday painter who collected Uzbek nomad blankets, jewellery and weaving alongside paintings from across the Soviet Union.

I was initially under the impression he collected the modernists Stalin banned (constructivists, Chagall, Kandinsky) but it is obvious Savitsky preferred landscapes and portraits in a late-19th century style. Few of the paintings here are of note but they are historically fascinating – that these gentle canvases refuted the socialist realist style Stalin prescribed and thus were considered illicit is bizarre. Somehow Savitsky convinced the authorities to build a museum to house his collection, so gifting Nukus Central Asia’s oddest tourist attraction.

Surrounding the museum is a building boom: Nukus’s newfound wealth is rapidly transforming the city centre. Another building boom is also underway in Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital, where the old town is rapidly being demolished - protests against this briefly attracted international attention – and a mega-mosque complex of the kind normally seen in the Gulf states is being built.

Tashkent is a big city (three million residents) and its best architecture is from the Soviet era: a huge earthquake in 1966 flattened many structures and its rebuilding engaged exceptional architects. This has left lush Art Deco subway stations and an array of beautiful brutalist buildings that are internationally celebrated, none more so than Hotel Uzbekistan, a stunning structure that is in danger of demolition. Nation building has seen almost all traces of the USSR removed – not simply statues of Lenin but any reference to the 70 years of Soviet rule. War memorials now feature only a bronze statue of a weeping woman and the names of fallen soldiers, alongside their birth and death dates – the last entries are from 1988 (as Russia withdrew from Afghanistan). In their silence they speak volumes as to why the Uzbeks are determined to create their own history.

Are they succeeding? Any time we tried to discuss how things are today (in Russian) with taxi drivers or hotel employees we received either positive – “there’s no war. We got rid of the men with beards. Business is good!” – or elusive answers. Considering how brutally Karimov’s regime treated those who showed even the slightest dissent, it is understandable people keep their thoughts private. Right now Uzbekistan feels akin to the Syria I travelled through in 1999: people are friendly, it is safe and inexpensive, alcohol is widely available, women are free to dress as they please, the music – traditional and pop – is exceptional and there is plenty to see and do.

Will Uzbekistan go forward in prosperity and peace? Or will long-repressed forces burst through to upset a regime that has changed only slightly since Soviet times?

On our first afternoon in Tashkent we noticed the city’s main thoroughfare – three lanes each way – closed to all traffic travelling north, while uniformed policemen stood on the pavement at 10-metre intervals. I guessed what was about to happen as Craig Murray had detailed such in his memoir: the president and his entourage were soon to travel this road and no one else is allowed to share it. And so they did, a fleet of gleaming black limousines rushing past. Uzbekistan is opening up – exactly how open we will have to wait and see.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37