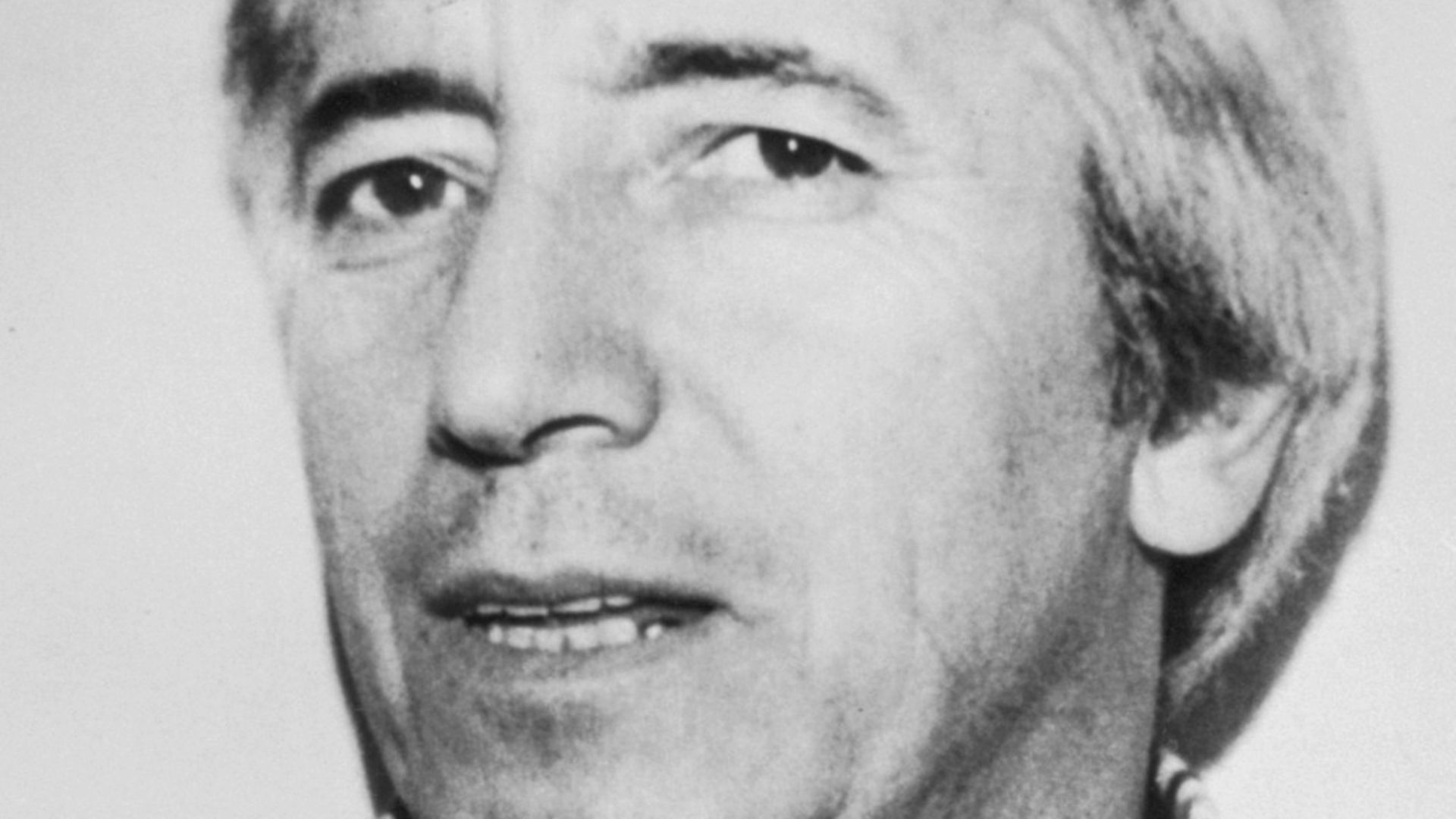

CHARLIE CONNELLY explores the life of Georgi Markov – the dissident Bulgarian writer who was assassinated in London.

At 10.30pm On September 7, 1978, Georgi Markov arrived at his home in Clapham, south London, after a long shift at the BBC World Service. He was due to return to work early the next morning and bedded down in his office for the night so as not to disturb his wife. At 2am however, Annabel Markov heard him being violently ill. When she took his temperature, the thermometer read 104 degrees.

Annabel phoned their doctor who advised her to keep Markov as cool as she could and to call again in the morning if there was no change. She sat up with her feverish husband for the rest of the night, dabbing his face with a cold flannel and listening to what he told her about the strange thing that happened to him that afternoon.

Markov had parked his small green van as usual close to the National Theatre, climbed the steps up to Waterloo Bridge and waited for a bus. He could have walked to Bush House from there but he was keen to get to work as quickly as possible to record his regular broadcast for the BBC’s Bulgarian service.

He liked to park near the National Theatre. It helped him feel close to the medium in which he’d found the most success, at least before he’d left Bulgaria nine years earlier. It was harder to break into British theatre, especially as a foreign playwright, but who knows, maybe one day he’d be parking at the National Theatre because one of his own plays was being staged there. He had high hopes for one he was working on, The Right Honourable Chimpanzee, and he was also tinkering with two novels. But for the moment the broadcast work paid the bills. It also gave him a voice.

As he craned his neck looking for his bus Markov was suddenly aware of a sharp pain in the back of his thigh. He flinched and looked round. A thick-set man was bending down to pick up an umbrella from the pavement. He turned his face away from Markov, mumbled an apology, scampered across the road into a black cab and disappeared into the London traffic.

Markov rubbed the back of his leg. It couldn’t be, could it? Surely it was just an accident, a man in a hurry, losing control of his umbrella. His bus drew up, he boarded and sat upstairs, not sure whether he could actually still feel the pain in his leg or whether he was just worried about what it might mean.

He twisted in his seat for another glimpse of the National Theatre and thought about how his last day in Bulgaria had begun at the theatre watching a performance of his own work, a day that had led directly to him now crossing Waterloo Bridge on a bus, worrying about a sting on the back of his thigh.

On the morning of June 15 1969 Markov’s play Az Biakh Toi, ‘The Man Who Was Me’, was being staged at Sofia’s Satirical Theatre for the first time in front of an audience, with its author in attendance. During the interval a senior figure in Bulgarian state security walked up to Markov and denounced the work loudly, deliberately and publicly as a ‘Czech play’. The events in Prague of the previous year were still fresh in the memory and Eastern Bloc governments were becoming ever more uneasy at the prospect of similar protests. It was at that moment that Markov knew he had to leave, and fast.

He already had travel papers for Italy, a planned visit to his brother, and realising his permission to travel would be revoked as soon as the grumpy security official made the necessary calls he went straight home, threw a few things into a bag, jumped into his car and hit the road, first for Belgrade then the Italian border beyond. A late summer shower had just passed over as he left Sofia and the capital was bathed in a warm, golden light, giving him a final view of his home city drenched in rich colours that were, he wrote later, ‘pitilessly beautiful’.

He would spend two years in Italy before settling in London in 1971. He joined the BBC working for its Bulgarian service, writing and presenting Georgi Markov Speaks, a weekly diary of British cultural life combined with a critique of the Bulgarian government. He also broadcast for the Deutsche Welle network and the American-backed Radio Free Europe, but still hankered to return full-time to his first love – writing plays and novels.

In 1974 his play Let’s Go Under the Rainbow had been staged in London’s West End, while the same year The Archangel Michael received an award from the Scotsman newspaper after a successful run at the Edinburgh Festival. He met Annabel that year and they married in 1975.

When he’d begun his broadcasts in 1972 – including a series of satires called Personal Meetings With Todor Zhivkov that lampooned the leader of the Bulgarian Communist Party – he was tried and convicted in absentia for disseminating propaganda hostile to the Bulgarian state. Zhivkov had led Bulgaria since 1954 and had once feted Markov as one of Bulgaria’s cultural heroes. No longer.

Georgi Markov was born in Sofia in 1929, the son of an officer in the Bulgarian army, and worked as an engineer between occasional spells in sanatoria having contracted tuberculosis while working in a brick factory. He spent much of his spare time writing, and after the cultural thaw sparked by Stalin’s death in 1953 and Zhivkov coming to power in Bulgaria the following year, Markov was able to publish the first of a handful of science fiction story collections in 1957 before his 1962 novel Muzhe (‘Men’), charting the worries and issues facing a Bulgarian youth as he prepared to undergo his national service, established him as a Bulgarian cultural heavyweight. Muzhe was selected as the novel of the year by the Union of Bulgarians Writers and Markov was inducted into the organisation without having to undergo the customary lengthy selection process.

His first play followed soon after, The Cheese Merchant’s Good Lady, and was a huge success. Others followed, subtle critiques of life in communist Bulgaria, but as the decade progressed Zhivkov’s cultural leniency was replaced by a distaste for dissent. Markov was sidelined, until the outburst by the bureaucrat in a Sofia theatre that morning in 1969 made it clear he had no future as a writer in Bulgaria.

The Markovs’ doctor called at their Clapham home early on the morning of September 8 and immediately sent the ailing playwright to the nearest hospital, St James’ in Balham. There specialists discovered Markov’s white blood cell count, which should have been somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000, had rocketed to more than 33,000. They also examined the wound on the back of his thigh and found a pellet just beneath the skin, no more than 1.5mm in diameter, with tiny holes bored through its centre. Government scientists at Porton Down found that it had contained ricin, a highly toxic poison from the castor oil plant, in a quantity more than sufficient to make Markov’s survival impossible.

Markov’s murder remains unsolved but was almost certainly the work of either the KGB or Durzhvana Sigurnost, the Bulgarian secret service. A number of journalistic investigations have pointed the finger at an Italian-born Danish citizen known as ‘Agent Piccadilly’ as the man who administered the pellet via the point of an umbrella. Durzhvana Sigurnost’s files relating to Markov were destroyed as the regime collapsed in 1990, but later a cache of umbrellas modified to fire tiny darts and pellets was found in the interior ministry building.

A clear motive for and the timing of the assassination both remain elusive. Bulgaria had warmer relations with the west than most other communist states and not long before Markov’s murder had agreed readily to a West German request to hand over two suspected terrorists. It could be that Bulgaria, as a relatively small nation, had fewer emigrés loudly critical of the regime and Markov just stood out. It could have been a warning designed to deter other leading Bulgarian figures from defecting. After all, Markov’s brother in Italy said he’d been warned the broadcasts had been blamed for the defection of another Bulgarian writer, Vladimir Kostov, who had himself survived a poisoning attempt in Paris the previous week. It can’t be a coincidence the attack on Waterloo Bridge took place on September 7, Todor Zhivkov’s 67th birthday.

Markov lingered in hospital for four days before succumbing to the poison coursing through his veins and organs. Meanwhile a small green van remained parked by the National Theatre, an unfinished script on the passenger seat.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37