Charlotte Salomon’s short life was characterised by persecution and family suicides and ended at Auschwitz. FLORENCE HALLETT reports on the remarkable artwork with which she chronicled her tragic existence.

In the winter months of 1941, the German-Jewish artist Charlotte Salomon holed herself up in a hotel on the French Riviera, and worked. She worked as if her life depended on it, and to all intents and purposes, it did.

In hiding from the Nazis, and responsible still for the care of her grandfather, whose apparently predatory behaviour had led to the suicide of every female member of her family, the 24-year-old Charlotte had presented herself with a question: “Whether to commit suicide, or to undertake something quite insanely extraordinary.”

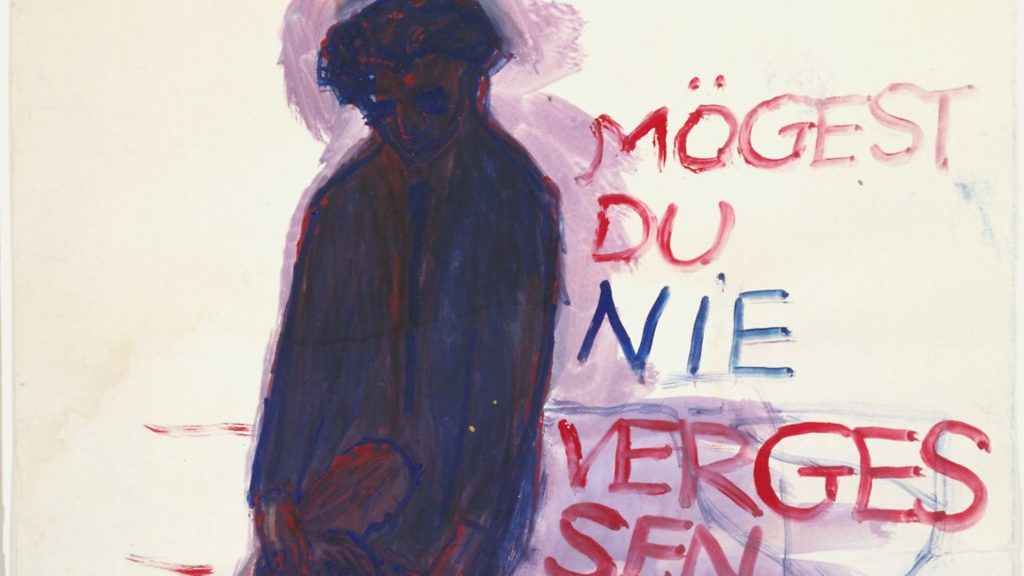

The something quite insanely extraordinary would be Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?), a loosely autobiographical work comprising well over 700 painted sheets, accompanied by texts and directions for music.

By the summer of 1942 this vast project was complete, but it was only months later that Salomon made her final edit, discarding several hundred gouache paintings and compiling an unbound, but carefully ordered series.

Now, 236 sheets from the series are on display at the Jewish Museum London in the first major UK exhibition of the work for two decades, with 50 sheets in this country for the first time.

Though it remained unknown until the 1960s, today Life? or Theatre? is recognised as one of the outstanding works of 20th century art.

In 1971, Salomon’s father and stepmother donated it to the Joods Historisch Museum, Amsterdam’s museum of Jewish history (JHM), which a year later staged the first major exhibition of the series.

That it survived at all seems hardly less than a miracle. In 1943, the German occupation of France extended to the south of the country, and the arrest and detention of Jews was pursued with new zeal. Realising the danger she was in, Salomon wrapped Life? or Theatre? in brown paper and gave it to her friend, the doctor Georges Moridis, entreating him to “take good care of it, it is my entire life.” A few months later, newly married and five months pregnant, Charlotte Salomon was arrested and transported to Auschwitz where on October 10, 1943, she was murdered, aged 26, her life contained and perpetuated in this unique and perplexing feat of creation.

Salomon called her series of gouache paintings a “singspiel” – a play with music – and her characters are introduced in a preliminary section much like a theatre programme. Salomon, her immediate family, and family friends remain easily recognisable, though their names have been altered to evoke something of their individual qualities and characteristics, while also weaving humour and warmth through an unimaginably bleak story.

Something of the author’s own character is revealed by the surname she gives to her own character, Charlotte Kann. Judith C E Belinfante, a former director of the JHM, and co-author of one of the more recent books on Life? or Theatre? suggests that Kanne, the German word for a lidded jug, is used to symbolise Charlotte’s withdrawn personality. Kann is also a form of the verb können (‘to be able to’), so that ‘Charlotte can’ becomes a mantra for the marshalling of resolve and self determination, a reminder that this was a project undertaken as a conscious alternative to suicide.

Alfred Wolfsohn, a down-at-heel First World War veteran, shell-shocked and unemployed, is renamed Amadeus Daberlohn. He is a singing teacher who joins the household as a voice coach to Salomon’s stepmother, the contralto Paula Lindberg-Salomon, the reference to Mozart implying a touch of genius, and Charlotte’s infatuation with him. Paula Lindberg-Salomon becomes Paulinka Bimbam, a name that is fittingly musical in its rhythm and range of sounds.

This deceptively jolly beginning gives way to a shock: on the first page the suicide of Salomon’s aunt Charlotte – her mother’s sister after whom she was named – is depicted in the blue-tinged half-light of a winter’s day. The accompanying text offers no explanation, but states: “On a November day, Charlotte Knarre left her parents’ home and threw herself into the water.” The tone is set, with death and female anguish at centre stage.

The suicides of Salomon’s female relatives occurred with chilling inevitability, as first her aunt, then her mother and then her grandmother took their own lives.

Both her mother and grandmother threw themselves from windows, and in recounting the suicide of her mother in each of the work’s three sections, she not only gives shape to her loss, but grapples with her sense of her own preordained fate.

Windows appear repeatedly: At times they resemble altars, but they are always portals to a different place, offering the possibility of reunion with the dead, or escape through one’s own suicide.

Just as the paintings switch between styles, mixing cartoon strips and dream sequences with close-cropped, cinematic frames, so too does the text.

Sometimes integral to the painted sheet, sometimes inscribed on a tracing paper overlay, the text offers a magpie collection of voices and styles that range from newspaper reports to short, sing-song rhymes, or direct quotes that mimic the speech of her characters.

For all that it looks in many ways rather like a storyboard for a film, or a script for a play, the piece was never intended to be performed, but functions instead as a private, internalised performance – an act of remembrance – to be carried out within one’s own head, complete with musical accompaniment.

Salomon was 15 on January 30, 1933, when the Nazis came to power, the moment marked in the prologue by a painting that pulses orange with the sinister dynamism of a Nazi rally.

With its high viewpoint and cropped composition it evokes the film reels that were shot and broadcasted in quantity, and is a rare example of Charlotte’s focus moving beyond the confines of the family circle, and in the following sheets she zooms back in on a series of family members and close friends so that we “see how this affects the different human-Jewish souls!”

As we embark on the main section and epilogue, where the impact of Nazi persecution intrudes ever more insistently, a compressed time frame introduces a mounting sense of claustrophobia, as death looms ever closer.

As the lives of Salomon and her circle become ever more circumscribed, the imaginative element of her narrative takes flight. In the main section, Salomon’s devotion to Wolfsohn – whose ideas about the redemptive power of art inspired Salomon to create Life? or Theatre? rather than killing herself – finds some resolution in the affair between Charlotte Kann and Amadeus Daberlohn.

The membrane between life and art is at its most porous in the sections concerning Daberlohn, and in one of the work’s more meta moments, he says to Charlotte: “One day people will be looking at us two.”

Salomon’s entire adult life was spent severely restricted by the Nazis, and when she was finally admitted to art school in 1935 she was the only Jew in her class, allowed in, it was explained, because her non-Jewish appearance and withdrawn character posed no threat to Aryans.

The last straw came in 1937 when Salomon entered a competition and discovered that her pen and ink drawing Death and the Maiden would not be awarded first prize since Jewish students were not permitted to win prizes.

Despite such restrictions, Life? or Theatre? shows a wide knowledge of art and visual culture from Munch, Matisse, and Van Gogh to Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling, seen on a trip to Rome in 1934.

Her knowledge of music, from Bach and Schubert, to folk songs and music hall hits, is surprisingly broad, and indicates perhaps the levels of education expected among the Berlin upper middle class at this time.

Life? or Theatre? is dedicated to Ottilie Moore, an American living in France who gave shelter to Salomon and her grandparents as well as countless others fleeing Nazi persecution.

Moore recognised Salomon’s talent, and bought paintings from her, provided her with materials, and in 1941 paid for her to retreat to the Hotel La Belle Aurore, at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat.

The epilogue reveals the state of profound distress that afflicted Salomon by the time she came to make her series. Her relationship with her grandfather deteriorated following the suicide of her grandmother, which she herself witnessed, and Salomon’s depiction of her grandfather as multiple talking heads, giving her the shocking news that in fact her mother, too, had killed herself, makes clear his insistent, bullying manner.

In fact, the epilogue, and a letter previously withheld by the family, reveal that Salomon’s grandfather was far more than a bully. The final sheets of Life? or Theatre? show Salomon and her grandfather in a dispute over sleeping arrangements, her grandfather ignoring her distress and saying “You can lie down in a bed with me just like that… I’m always for what’s natural”.

As Griselda Pollock points out in her book Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory, “The phrasing chillingly alerts particularly those who work with the victims of incest to the real possibility that, in addition to a legacy of feminine melancholia, this young woman was left prey to a sexually abusive grandfather”.

The letter, believed to have been addressed to Amadeus Daberlohn, was partially destroyed by Salomon’s stepmother, but seems to have included a confession to the murder of her grandfather, who collapsed in the street in February 1943, having eaten an omelette laced with barbiturates.

Separate from the main work, but addressing the fictional character Daberlohn rather than his real-life counterpart Wolfsohn, Salomon’s letter offers a final, perplexing twist to her story. Disturbingly autobiographical, but a consummate work of art, Life? or Theatre? stands as a testimony to the redemptive power of art and the courage of a woman whose vile death cannot detract from the beauty she created.

Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre? is at the Jewish Museum London, until March 1, 2020

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37