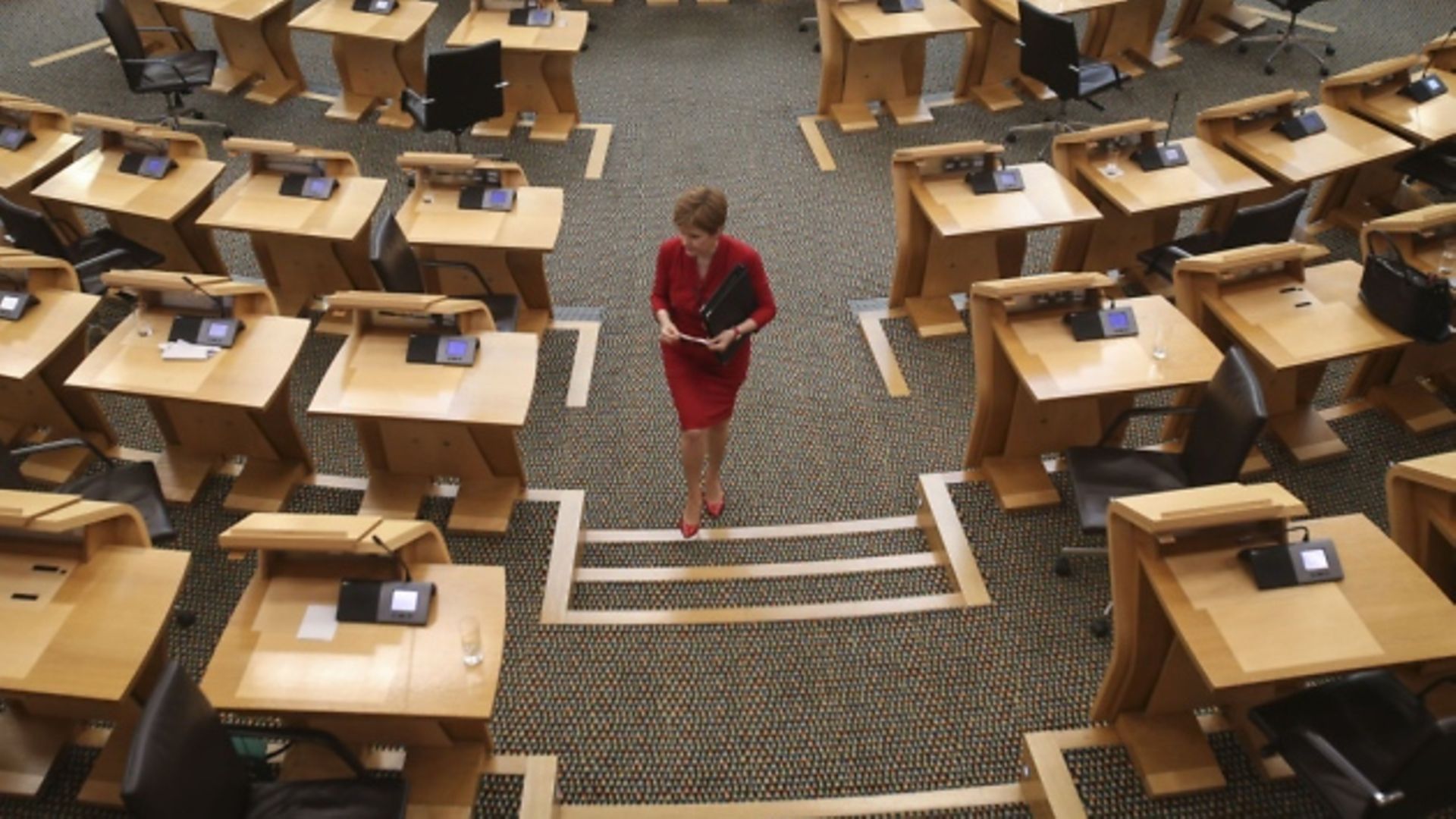

Scotland’s first minister is on a winning streak. Nicola Sturgeon’s personal approval rating is sky-high. Her party leads by miles in the polls, despite having been in power for more than 13 years.

Her Scottish National Party’s cherished dream and raison d’être – Scotland’s independence – now appears to be the choice of a majority of Scottish voters. Can she do no wrong?

It certainly appears that there is nothing that can stop the SNP. Whatever they mess up, and however they bungle, they come up smelling of roses.

Scotland’s coronavirus outbreak has been one of the worst in the developed world. With over 4,200 Covid-19 deaths which saw the virus mentioned on the death certificate, only a handful of states have done worse on a per capita basis. This would normally blow a hole in anyone’s reputation for competence: except, of course, that one of those countries suffering even more was England, grist to the nationalists’ goal of separation.

No-one can say that the Holyrood government did well during the coronavirus outbreak. That’s not a particularly harsh criticism, because the disaster came on suddenly and caused unique difficulties for any administration. But allegations of an early cover-up over a Nike conference in Edinburgh, a paltry testing effort and now a resurgence in case numbers are no hallmark of success either.

Scotland’s disastrous handling of its school leaving qualifications is another case in point. Anyone looking at a universal calculation of unique and individual grades should have got shivers running down their spine much faster than they did.

Yet the first minister and her education secretary, John Swinney, took nearly a week to see the writing on the wall and swerve rather than smash into it.

Their saviour? That’s obvious, because he sits in Downing Street and poses as an avuncular national figurehead, occasionally baring his teeth – as over devolved powers or a no-deal Brexit – only as a counterpoint to the jolly, bouncy character he’s invented.

That fictional simulacrum, of course, is called ‘Boris’, and in his guise as prime minister Johnson has come to signify almost everything that many Scots loathe about the Union.

It’s worth pausing at this stage to consider just how dominant Sturgeon’s party has become, and why. The last three opinion polls for next May’s Scottish election, all from different pollsters, have thrown up leads of 33%, 27% and 37% in the constituency part of the poll.

That’s a wide range of results, but they all would mean a large overall majority for the SNP on well over half the vote – quite a way up even on the 46.5% they gained in 2016.

What’s driving that? Well, it’s hard to conclude that it’s anything other than the vacuum of leadership on the other side of the aisle.

The last YouGov poll in Scotland gave Johnson a terrible score on whether he was doing ‘well’ or ‘badly’ (-54), while Sturgeon racked up a stratospheric approval rating (+50). One might suggest that lagging your main opponent by over a hundred points is a sub-optimal situation.

From the moment that Johnson eased hard lockdown in early May, and replaced his ‘Stay Home’ slogan with a message to ‘Stay Alert’, his stock has fallen: in Scotland and Wales, that means that the well-known rally-round-the-flag effect, which sees voters stand by their leaders in a real crisis, has transferred even more strongly to the just slightly more cautious governments in Edinburgh and Cardiff.

They can win the Scottish parliamentary elections next May very easily. The SNP’s Scottish opponents, as well as their London rival, are ineffective and invisible. The Scottish Tories’ new leader, Douglas Ross, is a fluent media performer, but has had little time to make an impression. His seat is also, as yet in the Westminster, and not the Edinburgh, parliament. Scottish Labour’s titular ‘leader’, Richard Leonard, is a living Invisible Man act most Scots would struggle to pick out of a lineup.

Even so, all of these gifts to the SNP should make them wary. Their apparently unquestionable dominance rests on parts of the political puzzle that could change, not the determined march to nationhood many imagine.

It is all too easy to appeal to this or that ‘structural’ reason why large-scale changes are happening, rather than understanding the proximate and immediate political context too. Johnson, coronavirus and the weakness of their opponents are supporting the SNP’s ratings right now.

But take away those factors – just as Brexit and Corbynism will no longer really help Johnson at the next UK election – and things might look very different.

It’s easy to imagine from the polls that there is a groundswell of Scottish national feeling. But whatever the short-term movements of opinion since the advent of the Johnson premiership and Brexit, there is little evidence of a really strong, long-term realignment of national feeling and self-perception.

There was a general move downwards, not upwards, of those voters feeling ‘wholly or mainly Scottish’ between devolution in 1999 and the first independence referendum in 2014: only thereafter did the number tick back up a little.

Even after that very divisive battle, YouGov found that ‘Scottish not British’ or ‘more Scottish than British’ went up from 51% in January 2012 to 57% in June 2018. All of this is hardly the earthquake you might expect from some of the numbers quoted in headlines.

Most Scots have long lived with the fact that they in general see themselves as Scottish, but might feel somewhat British as well; or (for fewer of them) that they feel British, but are definitely Scottish too.

There need not be any contradiction in that blurry framing, just as there wouldn’t be after independence either.

One could say the same of Brexit. One of the main drivers of the SNP’s success right now is the understandable feeling, on the part of many Scots, that they are being dragged out of the European Union against their will.

Polarisation around this issue seems to be one of the main drivers of pro-independence feeling: the last YouGov poll on that question showed that 53% of Scots favoured a Yes vote in a second referendum, a heavily Brexit-related choice that saw 60% of Remainers, but only 35% of Leavers, opting to abandon the UK.

There is a long way to go in this debate. A new referendum cannot possibly happen before 2022 at the earliest, and may be delayed for years by Conservative resistance or wrangling at Westminster. Any number of things can change in that time, as they have since the SNP’s relatively disappointing Westminster election performance in 2017.

What seems unlikely today can reappear as tomorrow’s received wisdom. Maybe the Westminster government will seal a trade deal with Brussels, drawing some of the sting from that issue. Rapid deployment of an effective vaccine could make coronavirus seem like a thing of the past, and, if the UK government has bought enough doses, begin (unjustly) to seem like a ‘British’ success story.

The Conservative government could be displaced in 2024 by a Labour-led administration under Keir Starmer – a prime minister Scots are likely to find much more acceptable, and who might be governing with the SNP’s approval.

The SNP is not a happy ship behind the scenes, and Sturgeon is their only really plausible leader right now: any scandal or really egregious policy disaster could change things. And so on.

Stugeon’s course forward is a tightrope, like all leadership – akin to John Major’s and David Cameron’s attempts to ride the Eurosceptic tiger without getting eaten by it, Tony Blair’s attempt to spend much more money on working class and low-income England without middle class voters minding, or Theresa May’s ill-fated efforts at Brexit compromise.

All of those examples show you, of course, that after riding high a spectacular fall may follow.

Scottish independence needs now to be taken very seriously indeed. Its likelihood is rising strongly.

But as ever, the winds and seasons and sands can shift very quickly. As in Shelley’s epic vision of Ozymandias, King of Kings, Sturgeon’s opponents look for now on her works and despair. But there are plenty of ways that the edifice could still turn into a colossal wreck.

Glen O’Hara is professor of modern and contemporary history at Oxford Brookes University. He is the author of a series of books and articles about modern Britain, including The Paradoxes of Progress: Governing Post-War Britain, 1951-1973 (2012) and The Politics of Water in Post-War Britain (2017). He is currently working on a history of the Blair government of 1997-2007

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37