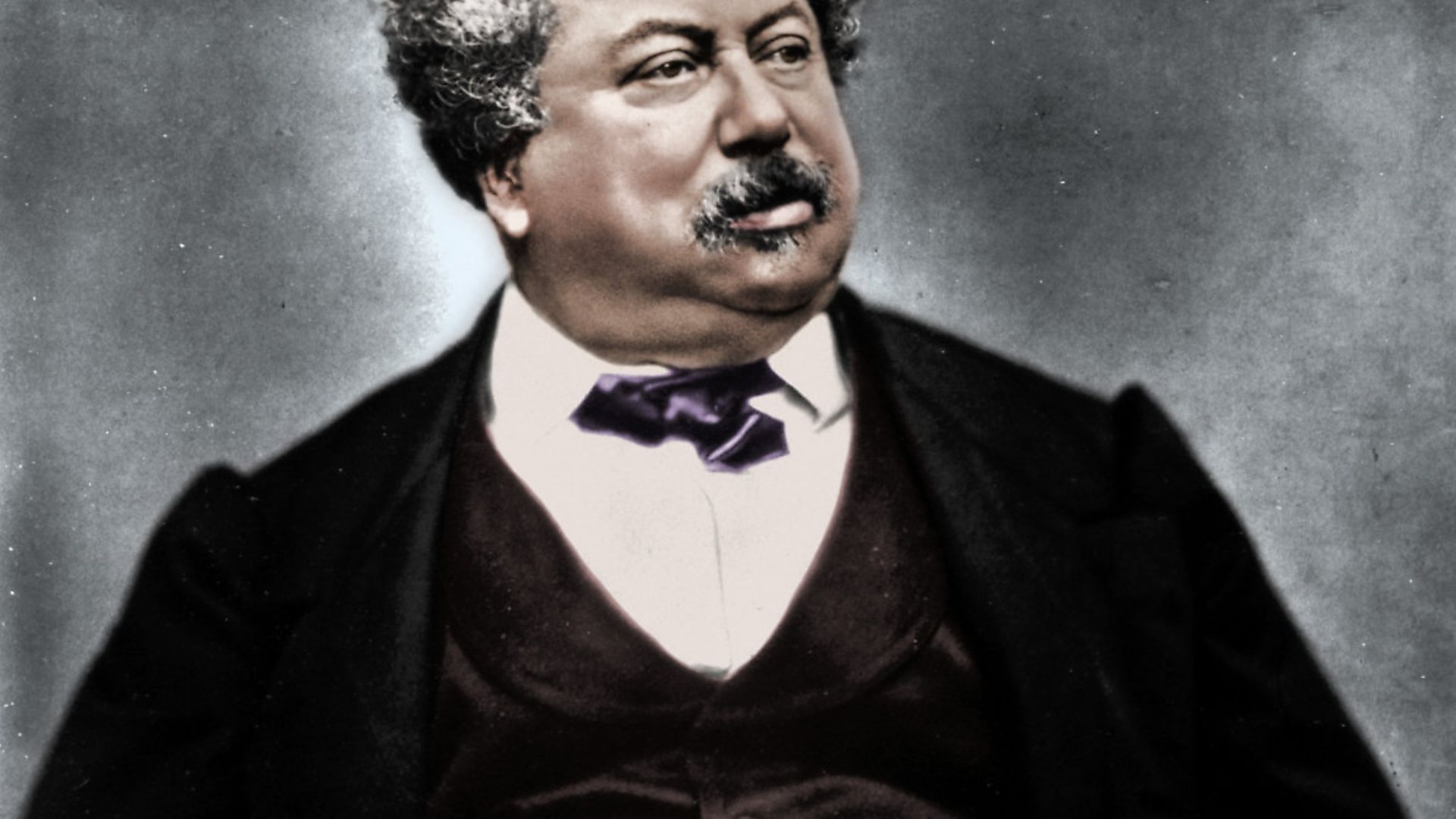

#78 Alexandre Dumas, July 24, 1802 – December 5, 1870.

At the height of his fame in the late 1850s, Alexandre Dumas was caricatured in the magazine La Vie Parisienne by Émile Marcelin. The leading French cartoonist of the day, pictured him holding two pens in each hand while scribbling on four pieces of paper at once as a waiter ladles soup into his open mouth.

Nobody can say with absolute certainty just how much work Dumas published in his lifetime but he was certainly one of the most prolific writers ever to put ink to paper. More than 650 books is one reliable estimate of his oeuvre, while the venerable set that makes the grand claim to be his complete works runs to 301 volumes containing some 37 million words, an output which if spread over the 40-odd years of his literary career works out at a shade under 18,000 words per week, every week.

These startling numbers are blurred slightly by the supposition that not everything published as Dumas’ work actually came from his pen. Theories range from him agreeing to put his name to a few manuscripts by struggling writers knowing that the resulting sales would ease their financial burden, to Dumas employing a disciplined team of ghostwriters churning out works the man himself never even saw, let alone wrote.

He wasn’t above a bit of plagiarism here and there either: a chunk of his early play Henri III And His Court, a major work in the canon of French Romantic drama, was lifted almost intact from a translation of Schiller’s Don Carlos.

Whatever the truth behind his remarkable productivity it was just another extraordinary aspect of the Dumas phenomenon, a man whose life was as dynamic and adventurous as his two enduring works The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo.

Dumas was a combination of immense talent, irresistible charisma and enormous ego. After holding court at a dinner for government ministers one evening, for example, he told a friend he would have been ‘bored to death had I not been there myself’, while one biographer identified as many as 40 women with whom he had extra-marital affairs. When the French government lent him La Véloce, a ship of the line, for a journey to North Africa Dumas awarded himself a 21-gun salute as they sailed into Tunis harbour.

‘Tunis, courteous as always, returned our salute,’ he wrote, ‘perhaps not as promptly or correctly as we would have wished.’

He lived his life at breakneck speed to the point where he had trouble keeping up with himself, especially financially. His literary prolificacy was due in no small part to a lifelong struggle to keep his massive income ahead of the equally massive expenditure that fed his enormous appetites and enthusiasms.

Dumas didn’t just settle for writing plays, for example, he built his own theatre, and when he’d set off on one of his epic journeys around Europe or North Africa he’d take what amounted to an entire mobile household with him (usually leaving lucrative newspaper and magazine serialisations dangling mid-story until his return, much to the horror of the publications forking out huge sums for them).

‘He was the most generous, big-hearted being in the world,’ wrote the Paris-based English illustrator Watts Phillips. ‘He was also the most delightfully amusing and egotistical creature on the face of the earth. His tongue was like a windmill: once set in motion you never knew when he would stop, especially if the theme was himself.’

Although known almost exclusively today for his novels, Dumas was as versatile a writer as he was prolific. He possessed a keen eye for the main chance, turning his hand to almost any genre that proved popular while identifying the subject matter he considered most likely to maximise his revenue. One of his early successes was a series of accounts of high-profile sensational crimes which the public lapped up, while his first bestselling book was En Suisse, a rollicking 1837 travel narrative about a journey he made through Switzerland. He went on to publish more travel narratives, memoirs and histories on top of his fiction. He even produced a multi-volume Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine.

Somehow Dumas also found the time to be politically active. His father Thomas-Alexandre, the son of a French aristocrat and Haitian slave (many contemporary caricatures of Alexandre were openly racist in their depiction of the writer), was a distinguished general under Napoleon but died when Alexandre was four years old.

As his mother subsequently struggled to make ends meet, Dumas grew up in a paradoxical mixture of poverty with an aristocratic name. As a young man his name earned him a job in law offices attached to Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, and in 1830 Dumas was an enthusiastic participant in the July revolution that ousted Charles X and placed Louis-Philippe on the throne.

He helped with the construction of barricades, found himself commanding a ragged detachment of 50 revolutionaries and managed to single-handedly persuade an entire garrison at Soissons to vacate the gunpowder store they were guarding.

In 1859 Dumas met Garibaldi who asked him to rework and translate his memoirs in order to publicise the Italian general’s campaign for national unification. Dumas became such an ardent supporter that he took to gun-running for Garibaldi in his schooner, the Emma. Political zeal never quite eclipsed his innate Dumas-ness, however: he missed the fall of Palermo because he stayed on in Marseille after picking up a shipment of weapons to throw a huge party, then called in at Sardinia to go hunting wild boar for a couple of days.

When Naples fell Dumas was moored in the bay where he’d been churning out revolutionary pamphlets. He organised a celebratory firework display, was feted as a hero and spent a year living in a Neapolitan palace where he founded a newspaper that he wrote almost entirely himself in Italian.

It was this kind of ceaseless zeal that helped establish Dumas as one of the first celebrities in the modern sense of the word. His fame was extraordinary. During two years he spent in Russia in the late 1850s Dumas travelled to the vast Lake Lagoda, Europe’s largest lake, close to the modern border with Finland, and endured a long, storm-tossed voyage to the remote monastery on the island of Valaam. After a journey of several nauseous hours Dumas was greeted by the abbot, who immediately pronounced himself delighted to meet the esteemed author of The Three Musketeers. He was even recognised in the street in Saratov, a Russian town on the Volga not far from Kazakhstan.

It’s a level of fame that remains undiminished. In 2005, The Knight of Sainte-Hermine, a novel left uncompleted at his death in 1870, was finally published in France where it immediately sold a quarter of a million copies.

In 2002 as part of the celebrations marking the bicentenary of his birth Dumas’ ashes were interred at Le Panthéon in a ceremony presided over by the French president Jacques Chirac and broadcast live on television. Chirac praised how Dumas had ‘helped to construct our national identity’ and in a frequently candid oration expressed sorrow for the prejudice Dumas had faced during his lifetime as a result of his mixed race origins, hoping the interment was ‘making right an injustice’.

‘With you we have been alongside d’Artagnan, Monte Cristo and Balsamo,’ he said, ‘travelling the highways and byways of France, traversing the battlefields and visiting palaces and fortresses. With you we explored, torch in hand, dark corridors, secret compartments and underground passages. With you, we dreamed. With you, we will dream again.’

Dumas’ enduring success wasn’t just down to being prolific, he was a born storyteller who knew instinctively how to lead his reader to an escape from everyday drudgery and how to author their dreams. His wide travels betrayed a natural curiosity (even if many of his adventures were designed to stay one step ahead of creditors) that gave his work a grand European scope in a tumultuous European century.

As Victor Hugo put in 1872, two years after Dumas’ death: ‘The name of Alexandre Dumas is more than French, it is European. It is more than European, it is universal.’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37