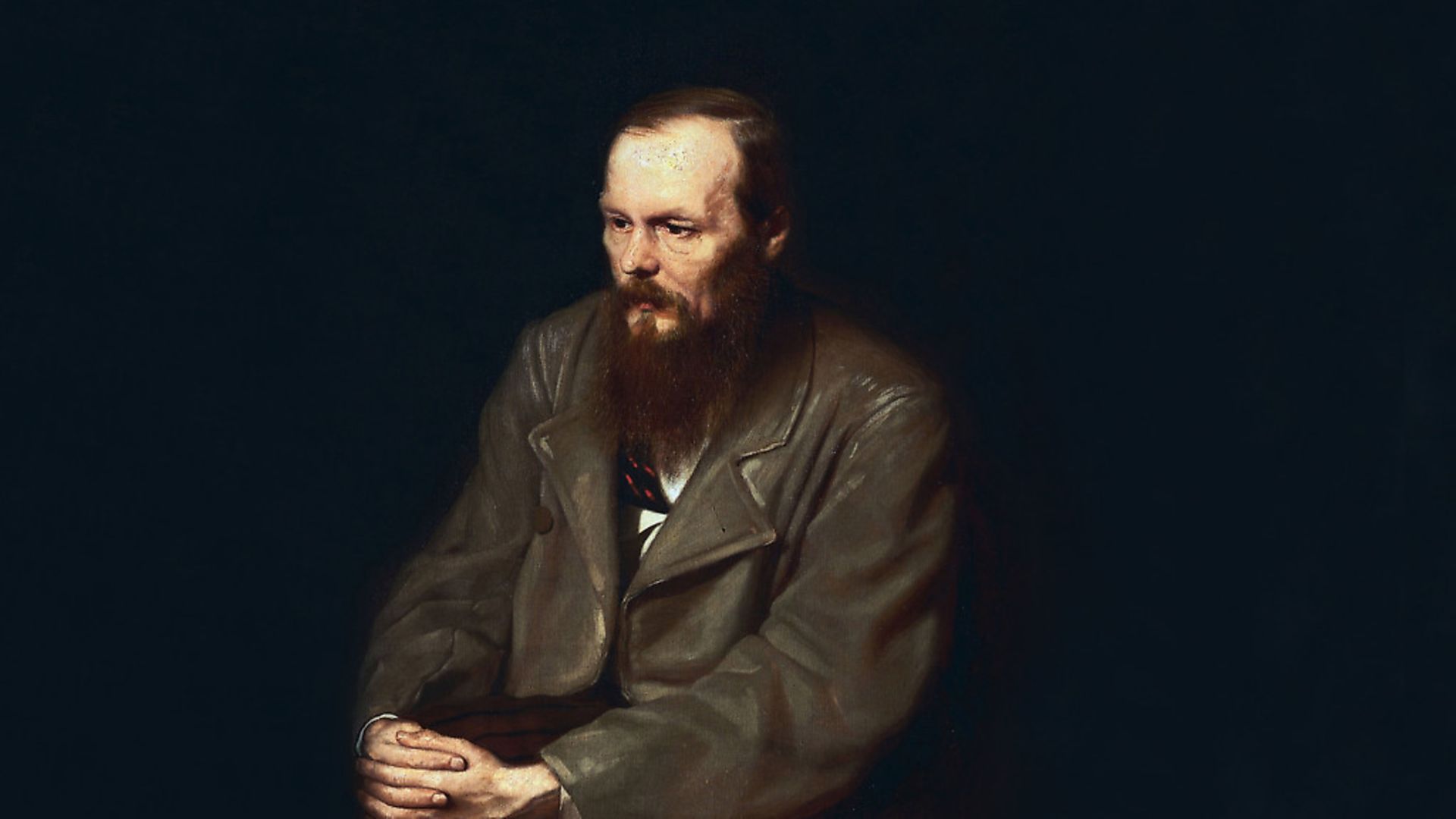

On the anniversary of his death CHARLIE CONNELLY takes a look at novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky in this week’s Great European Lives.

By December 22, 1849, 28-year-old Fyodor Dostoevsky had been imprisoned inside St Petersburg’s Peter and Paul Fortress for eight months. Charged with membership of utopian-socialist discussion group the Petrashevsky Circle by a Tsarist regime determined to avoid the wave of revolutions that had swept Europe the previous year, not to mention still jumpy from the failed 1825 Decembrist Uprising, on that cold morning the novelist and his co-conspirators found themselves being loaded in silence into carts and driven out through the fortress gates.

After crossing the Fontanka River, the procession halted at Semyonovsky Square where the men saw three thick wooden stakes had been driven into the ground. Nearby stood a group of soldiers preparing their rifles and a priest in full robes. A terrible truth began to dawn.

When they were taken down from the carts the men were read a proclamation confirming that a sentence of death had been passed upon them and would be carried out immediately. The prisoners were lined up three abreast and ordered to change into long white garments as the priest called upon them to make a final confession.

The first line, including the group’s leader Petrashevsky, were marched to the posts, had their hands tied behind them and were offered hoods. Men around Dostoevsky, who was in the second line, started to weep; some grew angry and were silenced with rifle butts. The author himself, meanwhile, wrestled with the realisation he had minutes to live.

The firing squad lined up and the square fell silent but for the wind blowing along the river. The captain of the squad raised his cutlass ready to give the order to fire when suddenly in a thunder of hooves and rattle of wheels another cart pulled up in the square. Out jumped an officious-looking military man with a document in his hand which was presented to the captain then read to the convicts.

The document was, he said, from the Tsar himself showing clemency by commuting the men’s death sentences. The whole execution scene had been an act of mental cruelty so harsh that Dostoevsky later said it drove one of his fellow captives insane. Instead of facing a firing squad the author would be sent to a prison camp in Omsk, Siberia, for four years during which, as the highest category of prisoner, his wrists and ankles would be permanently shackled. After that he would be conscripted into the army for an indefinite period.

‘In summer, intolerable closeness; in winter, unendurable cold,’ he wrote of his Siberian experience. ‘There was no room to turn around. From dusk to dawn it was impossible not to behave like pigs.’

Dostoevsky’s 1861 novel The House of the Dead drew directly on his Siberian experiences: brutality and wanton cruelty at the hands of the guards, the inherent evil of some of the inmates yet also incidents of goodness and kindness even in the dreadful conditions in which they lived. Considered by Tolstoy to be Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, The House of the Dead also served as a thought-provoking manifesto for individual freedom.

Having faced his own death (in his novel The Idiot he would describe a condemned man and how, ‘his uncertainty and repulsion before the unknown, which was going to overtake him immediately, was terrible’) and endured extraordinary hardship and privation, not to mention the escalation of his epilepsy, it’s no wonder that Dostoevsky’s subsequent work was psychologically profound and wrestled with deep and eternal questions concerning the human condition. In his four great novels Crime And Punishment, The Idiot, The Possessed and The Brothers Karamazov in particular he explores the psychology behind rage, humiliation, murder, suicide and insanity that make them not only great novels but also works of insightful and iconoclastic philosophy.

Crime And Punishment, for example, follows its protagonist Raskolnikov who, fully prepared to gamble with destiny, decides the solution to his various problems and challenges lies in murdering an elderly pawnbroker. He mulls over justifications and motivations, that killing the woman would be morally acceptable because her money could then be put to better use helping others and that she is expendable because the nature of her business relies upon the exploitation of the vulnerable. He attempts to convince himself that good and evil are artificial constructs based in religion and that stripping them away from basic human morality means crime doesn’t actually exist.

For all its considered philosophical profundity, like most of his novels Crime And Punishment was written in a hurry. Released from prison and military service in 1854, Dostoevsky spent much of the next decade outside Russia, travelling widely in Europe in order to stay ahead of his creditors while running up higher gambling debts at card tables across the continent.

By 1864 he had lost both his wife and his older brother, taking on a stepson from the former and financial responsibility for the family of the latter. Deprived of the luxury of time by debts and poverty Crime And Punishment was written in haste, originally published in 12 monthly instalments from January 1866 in The Russian Messenger. The Idiot would appear the same way two years later.

In between, in 1867 Dostoevsky wrote his semi-autobiographical novella The Gambler in less than a month. Forced by an unscrupulous publisher to take on a book contract that came with a much-needed advance but also a penalty clause that saw the rights to all his previous works revert to the publisher for nine years should he deliver the manuscript late, he somehow managed to conceive and write the book alongside his monthly Crime And Punishment instalments for The Russian Messenger inside an all but impossible deadline.

Many if not most of Russia’s great writers prior to the 20th century were born into privilege if not the nobility itself: Pushkin came from a noble family, while Tolstoy was a count. Such status bought them time to think and write. While Dostoevsky wasn’t born into absolute poverty he was no noble: his father had been a military surgeon who became a doctor at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in Moscow.

By 1831 Dostoevsky senior, an alcoholic with a violent temper, had managed to work his way up to purchase a relatively modest estate but died in 1839, murdered by his own serfs according to some accounts. With his mother having succumbed to tuberculosis two years earlier, Dostoevsky found himself orphaned in his teens. Even then he was demonstrating the combination of philosophical inquisitiveness and innate self-confidence that would fire his fiction.

‘I believe in myself,’ he wrote to his elder brother Mikhail shortly after their father’s death. ‘Man is a mystery, a riddle to be solved, and if you spend your whole life trying to solve it you won’t have wasted your time. This mystery is my chief concern, for I wish to be a man.’

Such self-belief almost proved to be his undoing when he came to take up the pen. In 1846 Dostoevsky completed his debut Poor Folk. He’d shown the manuscript to friends who were so excited by its potential they took it straight to the noted literary critic Vissarion Belinsky, who immediately declared Dostoevsky both a genius and the natural heir to Nikolai Gogol. Belinsky’s high praise went straight to the author’s head and even his friends began to find him absolutely insufferable, so much so that when his second novel The Double appeared later the same year it was roundly trashed.

It would take that freezing morning in Semyonovsky Square, when he was suddenly faced with the yawning, fathomless unknown, to unlock the moral and philosophical depths of one of the greatest writers in the history of world literature and prompt a return to his writing.

Dostoevsky came to represent a particular Russia and Russianness in which the very essence of humanity, with all its triumphs and especially its flaws, is enmeshed with the landscape and people, giving form and unity to a tangible national consciousness.

To this day Dostoevsky’s work distils that Russianness. When, in the summer of 2013, the American whistleblower Edward Snowden was confined to a Moscow airport transit lounge waiting for his emergency asylum application to make its glacial passage through the Russian system, his lawyer handed him a copy of Crime And Punishment to pass the time.

‘He needs to know the Russian mindset,’ said Anatoly Kucherena. ‘The reality of life’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37