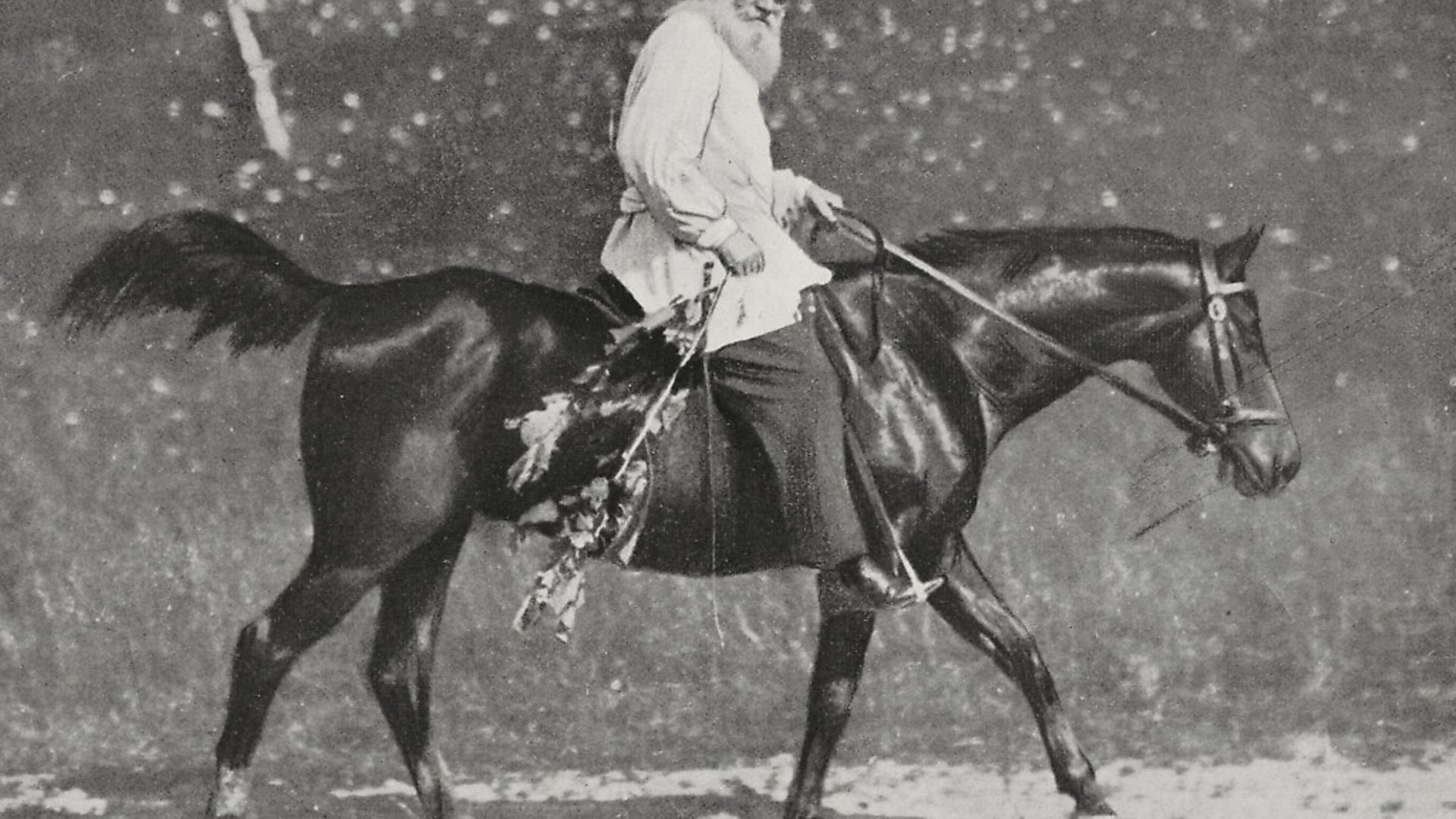

#76 Leo Tolstoy. September 9, 1828 – November 20, 1910

The station building is incongruously large for its rural setting. An imposing two-storey red brick construction, it looks out of place serving a backwater 230 miles south-east of Moscow where a regional passenger shuttle trundles in and out a few times a day and the odd clanking freight train rumbles heavily through. The station at Astapovo is immaculately kept, its pointing perfect and guttering freshly painted, the only apparent blemish being the stopped platform clock. For 108 years now it has shown five minutes past six, marking the moment when Leo Tolstoy died in a room at the stationmaster’s house early in the morning of November 20, 1910, at the age of 82.

A few days earlier Tolstoy had snuck out of the family estate at Yasnaya Polyana before dawn accompanied by his personal physician. His vague, ill-formed plan was to become a wandering teacher spreading the ascetic brand of Christian mysticism he had been espousing for the last years of his life. More prosaically, the octogenarian was leaving his wife.

Dressing in peasant garb and wearing a long beard, Tolstoy spent his last three decades turning out voluminous tracts on morality and religion that earned him both excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church and a band of dedicated disciples, many of whom took to living in the grounds at Yasnaya Polyana.

His wife Sophia, who had endured the transformation of her husband from rakish, aristocratic novelist to abstemious mystic, had reached the end of her tether.

Tolstoy – and by extension his entire household – had become a strict vegetarian who also abstained from alcohol and tobacco while preaching a nonviolent yet nihilistic form of political anarchism. In 1889 he’d written the novella The Kreutzer Sonata, practically a misogynists’ charter in which a man on a train pontificates on love and marriage, condemns married women as whores and asserts that married love inevitably turns to hatred, especially when the woman stops being able to have children.

Eventually the man, suspecting adultery, murders his wife. The book was immediately censored by the Russian authorities and the ever loyal Sophia had pleaded with them to release it.

It was the constant presence of Vladimir Chertkov that truly pushed her to the limits. Like Tolstoy, Chertkov was a former soldier from an aristocratic family, and when he met the author in Moscow in 1883 became an immediate and zealous convert to Tolstoy’s manifesto of strict abstinence and moral self-improvement. He established himself as the writer’s confidant, becoming an ever-present figure and constant thorn in Sophia’s side, not least when he encouraged Tolstoy to sign over the copyright to his work and deprive the family of their income.

Sophia came to regard Chertkov as the devil, even calling in a priest to exorcise his presence from the house, and the years of emotional abuse she received from her husband led to repeated threats of suicide.

‘Your overexcited state, anger and illness, your present mood, your desire for and attempts at suicide, show more than anything else your loss of self-control,’ Tolstoy wrote in the letter he left for his wife of nearly 50 years on the morning he crept away under cover of darkness. ‘As long as you don’t have that, life with you is senseless for me.’

Adding that he was doing what men of his age usually do, ‘leaving worldly life to spend my last days in solitude and quiet’, Tolstoy took his physician’s arm and vanished into the pre-dawn. He would never see Yasnaya Polyana, where he was born and where he’d spent almost his entire life, again.

After four days of travelling on crowded, draughty trains fogged with tobacco smoke the elderly Tolstoy developed breathing difficulties that turned into pneumonia. Taken off the train at Astapovo the ailing writer was recognised by the station master who offered a room in his house where Tolstoy was put to bed.

As the station had its own telegraph office it wasn’t long before news of Tolstoy’s condition spread across Russia and beyond: bulletins appeared in the world’s newspapers detailing every improvement and every decline. It was a live news event; Pathé even despatched a film crew from Paris. Chertkov arrived as quickly as he could with a select group of Tolstoyans and took control of the situation, meaning that when Sophia arrived she was refused permission to see her dying husband.

Pathé even shot footage of her stepping from her train carriage and walking unsteadily between two friends to the window of Tolstoy’s room, peering in, in an effort to catch a glimpse of her ailing spouse. It’s an affecting piece of footage even if it does look rehearsed.

There were two main reasons the world hung on the updates tapped out from the little telegraph room at Astapovo station: War and Peace and Anna Karenina. Not just two of the greatest Russian novels of all time but two of the greatest works of fiction the world has ever seen. On the face of it neither book should work, both being vast, sprawling and complex with huge rosters of characters, but such is the power and insight of Tolstoy’s writing the reader is drawn into the complex narratives.

Isaac Babel said that if the world itself could write it would write like Tolstoy, while for Chekhov, ‘our short stories, or even our novels, all are child’s play in comparison with his works’.

Tolstoy spent four years in the late 1860s writing War and Peace and completed Anna Karenina in 1877 after three years’ work. It was on finishing the latter that he fell into an existential crisis and experienced a religious awakening born out of a profound fear of death, a period that would lead him to describe Anna Karenina as ‘an abomination that no longer exists for me’.

Death had played a major part in Tolstoy’s life almost from the beginning. Born into the nobility as a count, he lost his mother before he was two and his father when he was nine. His grandmother followed a year later and his guardian a year after that. As an army officer he fought in the Crimean War, witnessing first-hand the gory carnage of 19th century battle, and when visiting Paris in 1857 attended a public execution where the sight and sound of the guillotine affected him deeply.

Tolstoy’s preoccupation with death never left him. Before his final illness, he had instructed friends and followers to record his impressions of his own passing as it happened, even devising a glossary of eye movements to answer questions in the event he couldn’t speak. Such was the chaos at Astapovo that nobody remembered the arrangement and Tolstoy’s death went un-analysed by its protagonist. He slipped into a coma and, barely a quarter of an hour before the end, Sophia was finally allowed into the room.

Tolstoy was a nobleman who aspired to peasantry, a bacchanalian who preached abstinence, an ascetic who lived comfortably, a soldier who espoused peaceful non-resistance and a man blessed with a profound insight into the human condition blind to the damage he caused to those closest to him. He wrote millions of words during his lifetime with many more written about him by people close to him, yet as a human being he remained distant and opaque.

‘He was very calm, with the calmness of one whose time of struggle is past,’ wrote the Guardian’s St Petersburg correspondent Harold Williams of a 1905 visit to Yasnaya Polyana, ‘and though he talked freely about current events and was kind and courteous after the gracious manner of Russian noblemen of the old school, one knew that his real life was hidden in some remote world of quiet contemplation.’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37