CHARLIE CONNELLY takes you through the fascinating life of environmentalist, Petra Kelly.

It was almost three weeks before the bodies were discovered.

Petra Kelly, 44, was found in bed, killed by a bullet through her left temple, at the home she shared with her 69-year-old partner Gert Bastian who was himself lying outside the bedroom door, a bullet wound in the top of his head from the Derringer pistol in his hand.

A raft of theories was put forward in the aftermath – an intruder disturbed, a politically-motivated assassination – but the most likely explanation remains that Bastian killed Kelly and then himself.

The reason why has never been established, one popular hypothesis being that his soon-to-be-opened Stasi file contained material he’d rather not see published.

Either way, the drama and mystery surrounding their deaths couldn’t detract from how the world had been deprived of one of its most tireless, passionate and effective environmental campaigners.

Kelly was, appropriately for a committed environmentalist, a force of nature. Green issues are a key aspect of political discourse today but this wasn’t always so: it was Kelly and her generation who battled to place the environment at the forefront of politics and she battled harder than most.

As a campaigner she was noisy, uncompromising and full of zeal, keen to get her hands dirty, far happier with a loudhailer in her hand at a public rally than in the stilted, ritualised talking shop of the Bundestag, where she served as one of the world’s first Green members of parliament.

She was a global face, travelling to demonstrations in the US, Australia, South Africa and the USSR as well as across Europe, giving passionate speeches against nuclear power and the arms race. She asked uncomfortable questions of the political elite with a refreshingly-brash approach that brooked no compromise.

By 1983 she was everywhere. In the West German elections of that year the Green Party, of which Kelly had been a founder member four years earlier and its most prominent public face, enjoyed their first electoral success: 5.6% of the vote and 27 seats in the Bundestag. As one of the first members of parliament from a specifically environmentalist party anywhere in the world, Kelly’s new position only increased her passionate activism.

Two months after her election she was arrested on Alexanderplatz in East Berlin after unfurling an anti-nuclear banner with the slogan ‘Swords into Ploughshares’. In July she turned up in Washington railing against the NATO resolution to place American mid-range nuclear missiles in Western Europe and in September she was at the heart of a blockade at an American military base in Baden-Wurttemberg.

In the autumn she appeared at an anti-missile rally in the West German capital Bonn, addressing a crowd estimated at 200,000. A trip to Moscow for a risky demonstration in Red Square, against Soviet SS-20 missiles and in solidarity with dissident nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, followed before a return to the Bundestag for the parliamentary vote on the US missile deployment.

The vote was lost and, although nobody realised it at the time, the slow death of the Green Party had begun. Formed from a federation of campaigning groups and activists the organisation had been riven by bickering over strategy from the start, with many members unhappy at what they saw as the personality cult developing around Kelly.

The Chernobyl disaster distracted from the infighting, its reverberations helping the Greens to almost double their presence in the Bundestag to 46 seats in 1987. It was a short-lived success, however. Reunification in 1990 came as a surprise to Kelly and her party; it was something they had opposed and in the upsurge of euphoria that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall the Greens’ open reticence saw them lose every seat at that year’s election.

By then, Kelly’s high profile and abrasive style had seen her fall out of favour in an increasingly-bureaucratic party anyway. Unwilling to make the deals and compromises seen as vital to increasing the party’s political influence, Kelly was to some extent spared the 1990 humiliation at the ballot box as she’d been deselected as a candidate anyway. She was left without a party, without an office and without an income. What remained were her global fame, irrepressible determination – and Gert Bastian.

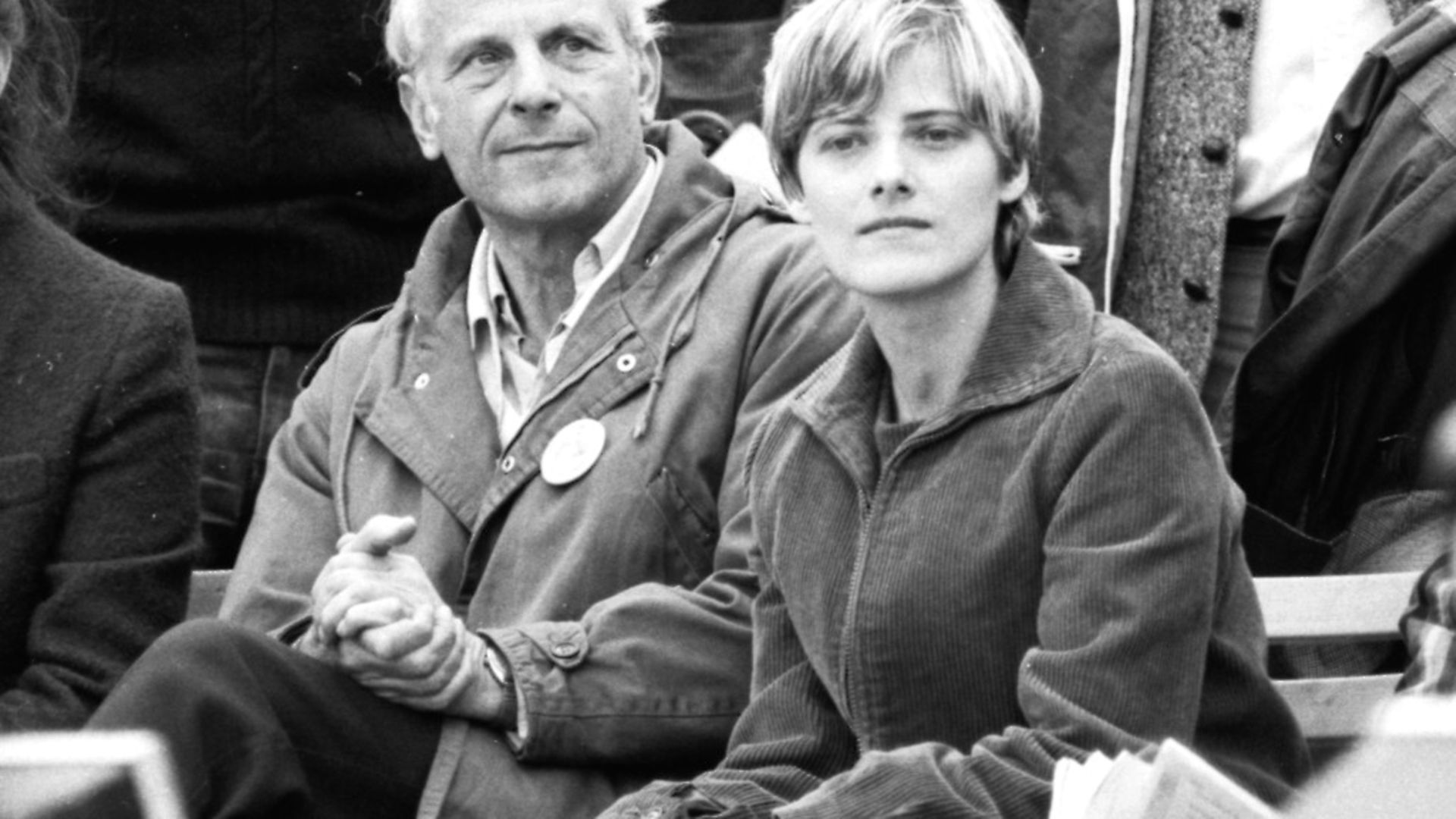

The couple had met at an anti-nuclear rally in 1980 and made an unlikely pairing, the fiery young woman and the white-haired former army general. The different eras that produced them were exemplified by how, on being introduced, Bastian without irony took Kelly’s hand and kissed it.

A former member of the Hitler Youth, Bastian had joined the Wehrmacht and seen action on the Russian front. When West Germany was permitted to form an army in 1954 he was among the first to sign up, but when, in 1979, Helmut Schmidt’s government agreed to site American missiles on German soil the man who by then was in charge of 18,000 troops resigned his commission.

Instantly he became a leading light in the anti-nuclear movement, one of that first batch of Green MPs as well as the protector, confidant and lover of Petra Kelly.

Most of Kelly’s romantic partners had been men much older than herself, and amateur psychologists don’t take long to note that her father abandoned the family at the age of six. For five happy years she was effectively raised by her grandmother before her mother met John Kelly, an Irish-American soldier, and the family moved across the Atlantic to Georgia.

While studying at the American University in Washington Kelly volunteered as part of Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential run and was voted the Outstanding Woman of the Year by fellow students on her graduation in 1970 – the same year as the personal tragedy that provided the catalyst for her political career.

Kelly’s half-sister Grace was nine years old when she died of cancer after three gruelling years of treatment in the US and Germany that had cost her an eye. Devastated by the loss, Kelly threw herself into investigating possible links between child cancer and nuclear power, convinced that excessive doses of radiation treatment at a clinic in Heidelberg had exacerbated Grace’s condition rather than treated it.

Returning to Europe for postgraduate study in Amsterdam, Kelly continued her campaigning and research and took a job at the European Council. There she embarked on a relationship with its 65-year-old president Sicco Mansholt, became appalled at the sexism she found (of the 1,600 staff at the Council, less than 100 were women) and exposed how Council money was being channelled into right-wing political groups across the continent.

This burning sense of injustice combined with the grief for her sister to forge in Kelly an unquenchable desire for truth and justice, a calling that led to her regularly working 20-hour days despite suffering with a persistent kidney complaint (she twice required emergency first aid during her time in the West German parliament).

It wasn’t that nobody missed her that led to Kelly’s body lying undiscovered for so long. Quite the opposite. Everyone just assumed she was out there somewhere, working, protesting, campaigning, seeking justice wherever it might take her.

‘In a world struggling in violence and dishonesty the further development of non-violence not only as a philosophy but as a way of life, as a force on the streets, in the market squares, outside the missile bases, inside the chemical plants and inside the war industry becomes one of the most urgent priorities,’ she’d said.

That she’d devoted her life to spreading a message of peace only exacerbated the tragedy of her violent end.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37