Remembering the world’s oldest mountain guide.

December 3, 1900 – June 14, 2004

One night in September 1921, as the Alpine climbing season wound down for the winter, a group of four young people filed out of a hut in the early hours of the morning. Two men and two women roped themselves together in pairs and set off into the night on the path leading up the mountain.

None of them had ever climbed a mountain before, the women were wearing long skirts and the candle lanterns they had brought to light their way kept going out. As Matterhorn expeditions go, this wasn’t the best-prepared.

At 4,478 metres there are higher mountains in the Swiss Alps but the Matterhorn is the most recognisable, its triangular peak standing out from the surrounding outcrops like a giant fin. “The most noble cliff in Europe,” John Ruskin called it, a challenge to climbers ever since Edward Whymper became the first to reach the summit in 1865. Four of his seven-man team died in a fall on the descent, a reminder that the Matterhorn might have been conquered but it was still a dangerous prospect for any climber, particularly an inexperienced one.

At the head of the four novices that night was Ulrich Inderbinen, three months shy of his 21st birthday. The ascent had been his idea, having seen in the route up the mountain a way out of the poverty of Alpine farming life. Having applied for a popular course in mountain guiding, Inderbinen was rejected on the reasonable grounds he’d never climbed a mountain in his life. The ascent with his sister Maria and two friends from their home village of Zermatt would put that right.

The climb had to be made at night because the quartet all had to work during the day, and without a guide of their own, or even a suitable map, they made their way up the dark slopes by following marks left by the boots and axes of previous climbers picked up in the dim light of their lanterns. “None of us knew what we were doing,” recalled an incredulous Inderbinen in later life. “The girls wore ground-length skirts and their everyday shoes.”

Somehow all four returned safely, Inderbinen made it onto the course and began in earnest one of the most remarkable mountain lives ever lived.

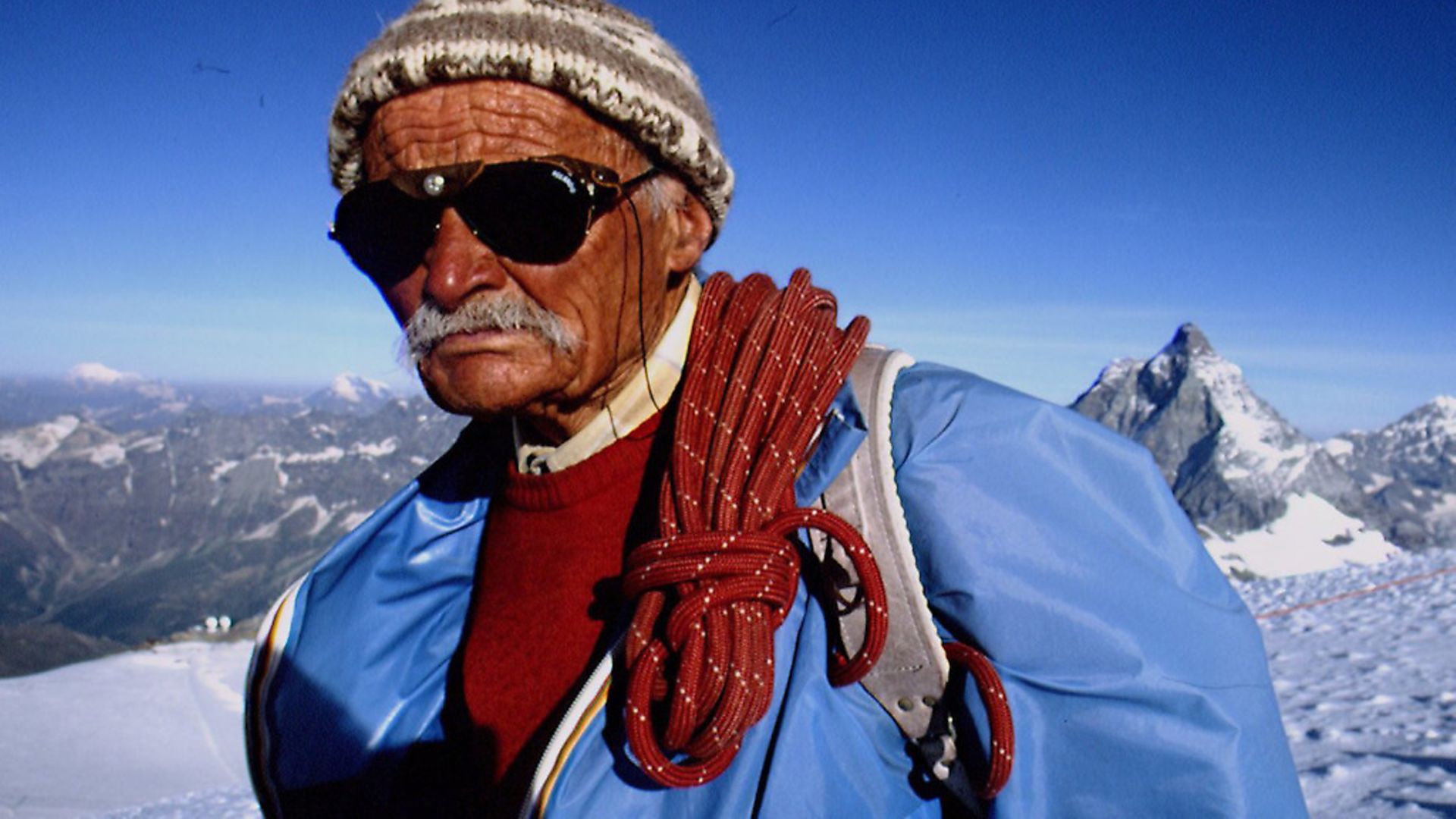

In the summer of 1990 a commemorative expedition climbed the Matterhorn to mark the 125th anniversary of Whymper’s first ascent. Video footage shows the group at the summit, a clutch of men and women with the shiny red faces of a life outdoors, all smiles beneath mirrored sunglasses and bandanas. Some of the party were arriving as the camera panned round, including one figure in a bright blue padded jacket with a rope looped over his shoulder, a dark hat that flopped to one side like a beret, sunglasses and a long white moustache.

Nearly 70 years after that first ascent and a few months short of his 90th birthday Ulrich Inderbinen was still climbing the Matterhorn. He’d just done it in four hours. A bottle was handed round, Ulrich raised it in toast and drank long and deep. “It’s simply a fascinating mountain,” he said, “still as appealing to me on my last climb as it was on my first.”

He’d lost count of the number of times he’d been at the Matterhorn summit but it wasn’t far short of 400. On that clear, sunny day in 1990 Inderbinen still had a good few years of guiding ahead of him, retiring at the age of 97 only when he realised he’d taken ten minutes longer to descend the Breithorn than usual. Pace was always the criterion by which he judged his expeditions. “I am never bored,” he told an interviewer as he turned 90, “as long as my clients don’t walk too slowly.”

One of the favourite Inderbinen stories was the occasion when some German climbers were alarmed to learn their guide would be a man in his late seventies. They registered their disquiet at the climb office but were told Inderbinen was the only guide available.

At the end of their day in the mountains before going their separate ways a sprightly Inderbinen turned to face the group, all of them breathing hard and leaning on their poles, and asked how they’d found their day. It was fine, they gasped, but they could have done with a few more rest stops given the pace they were going. “Ah, is that so?” replied the veteran guide. “Hmm, maybe you’d have been better off with an older guide.”

Inderbinen’s longevity was down to his extraordinarily good health. The only time he missed work through illness or injury was in 1958 after a client had slipped and fallen from an icy path while descending the Matterhorn. Inderbinen, in his late fifties at the time, held on to the rope to prevent what might have turned into a fatal incident until others could assist, dislocating his shoulder with the effort.

He didn’t visit a dentist until he was 74 and took up competitive skiing at the age of 80 (because, he’d admit with a chuckle, he knew he would be the only entrant in his age group so couldn’t lose). He rarely took holidays, but when he turned 92 his family forbade him to travel to Kenya where he’d planned to climb Mount Kilimanjaro. “I’ve no idea why they were so against it,” he grumbled.

The inner strength that would keep him skipping happily around the mountain tops as a nonagenarian had manifested itself at birth. Far from the modern winter sports resort of today, Zermatt in 1900 was a small village of around 700 people where during the first winter of the 20th century temperatures plummeted to -27. Even a hard-bitten Alpine community used to tough conditions found themselves struggling.

It wasn’t the ideal time for Frau Inderbinen to be giving birth – there was no doctor in the village and with deep snowdrifts cutting off the rest of the world no chance of fetching one either. Against the odds – Alpine infant mortality rates were high at the best of times – baby Ulrich not only survived but thrived.

By the age of four Inderbinen was spending his summers moving between tiny settlements up in the high Alpine pastures with his parents and siblings, tending cattle and collecting firewood, returning to Zermatt in the winters to attend school. Alpine farming was little more than a subsistence existence, hence his decision to try mountain guiding for the increasing numbers of visitors arriving in the area hoping to scale a peak or two.

He’d worked briefly as part of a tunnelling gang, dangerous work involving a long commute, where he realised his future lay on the mountains rather than inside them.

He qualified at 25 and his first client was a German doctor whom he escorted up the Matterhorn. In the book of references every guide kept the doctor wrote, “Herr Inderbinen showed himself to be thoroughly safe and reliable and I hope to climb with him again”.

Without connections to the hotel trade Inderbinen had to work hard initially to find clients, climbing the 5,000 feet to the station high above Zermatt every morning to meet new arrivals as they got off the train. When he’d finally established himself, the Second World War put a stop to tourism and brought military service for Inderbinen on solo ski patrols around the Theodul glacier at night, with a rifle over his shoulder but no torch or lantern. If his time in the Swiss army had one benefit, the nocturnal excursions gave him an uncannily accurate sense of direction, something that proved useful in later years whenever the mountain weather closed in.

He married Anna Aufdenblatten in 1933 after a five-year courtship, the marriage service taking place, as was customary, at 6am so everybody, bride and groom included, could go straight to work afterwards. Inderbinen built a wooden cabin close to the church in Zermatt – he was deeply religious and attended Mass every day – where he and Anna raised their family and where Inderbinen lived quietly and simply for the rest of his life. He retained his independence after Anna’s death in 1984 and was still chopping his own firewood into his nineties. As Zermatt became a busy tourism town and expanded beyond all recognition, Inderbinen’s life carried on as it always had, an oasis of contentment and calm. He never installed a telephone – prospective clients would find him in the town square every evening – and never owned a bicycle, let alone a car. The only time he left the region was to meet the Pope in Rome when he was 93.

Ulrich Inderbinen was a man of his time and out of time. His world was dictated by the rhythms of the seasons and the majesty of the mountains. He always knew nature was in charge, acceptance of which allowed him a long and rewarding life.

“Stress and haste are unknown to me,” he said in the last interview before his death at the age of 103. “I live as I climb mountains: at a pace that is slow and deliberate but also purposeful and regular.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37