As another Manson movie hits cinemas, JAMES OLIVER examines why this Hollywood story continues to beguile film-makers.

Fifty years ago, a couple of weeks after the first moon landing, a few days before Woodstock, came events that would, in their own awful way, become as emblematic of their era as the two peaks that bracketed them.

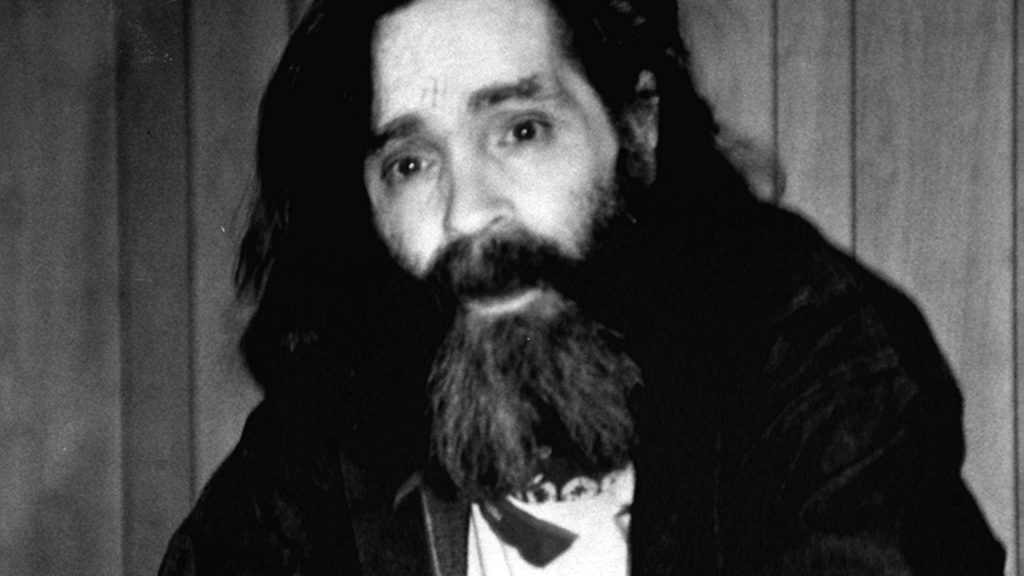

On the nights of 5th and 6th August, 1969, a hippy chieftain called Charles Manson sent members of his Los Angeles commune – they called themselves ‘the Family’ – out on killing sprees. The second night, they murdered supermarket owner Leno La Bianca and his wife Rosemary.

Terrible though this undoubtedly was, it’s sadly doubtful that their deaths would be so vividly remembered were it not for the first set of murders committed by the Family. These were in a house on Cielo Drive in the Hollywood hills, then being rented by Roman Polanski (who was in London that night) and his wife Sharon Tate. She was slaughtered, as were her three houseguests Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger and Wojciech Frykowski, and Steven Parent, a young lad who’d been visiting the caretaker.

The fascination with the Manson killings (as they came to be known) has many strands, but celebrity is a significant one. Beautiful young starlets are not supposed to die, and not like that (they stabbed Sharon 16 times; she was eight months pregnant).

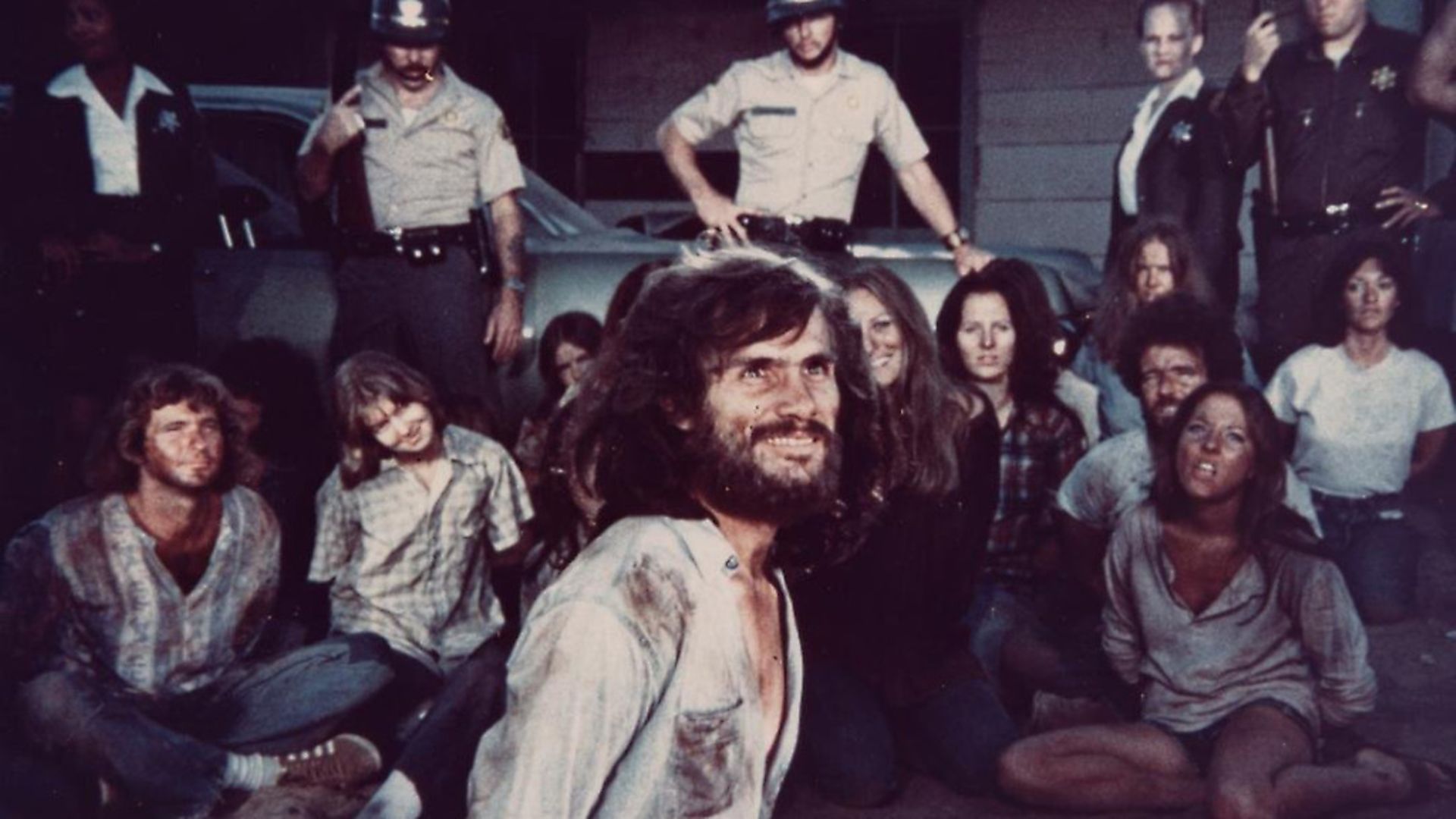

When the culprits were finally apprehended in December of that year, it became clear that the links to the entertainment world went even further. Manson was a failed singer-songwriter at the periphery of showbusiness; spiralling outwards, his story includes walk-ons for The Beach Boys, Neil Young, Doris Day, even Angela Lansbury. As if to provide ready-made symbolism, the family even lived on a ‘movie ranch’, an old set where episodes of The Lone Ranger were once shot.

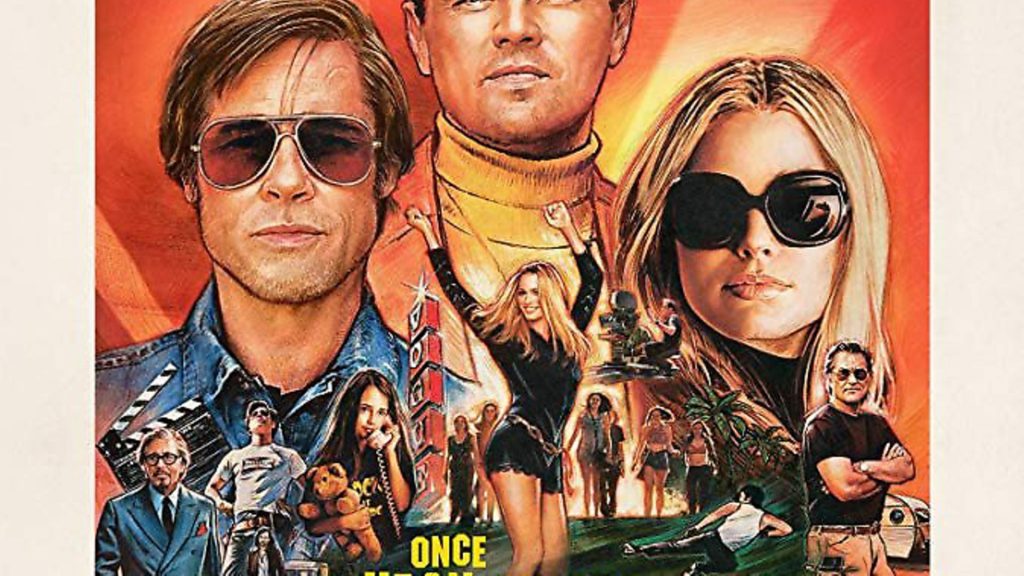

These were Hollywood crimes and it’s no surprise that the aftershocks have reverberated through Hollywood ever since. Quentin Tarantino has decided to use the summer of 1969 as the backdrop of his latest odyssey, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood; for those who prefer a more orthodox version, this year also sees the release of Mary Harron’s Charlie Says. Beyond the unfortunate connotations that title has for anyone who remembers British public information films of the early 1970s, this casts Matt Smith as Manson, although the real focus is on the young women who served as his groupies.

These are only the latest in a long line of productions informed by the cult leader and the killings, the most obvious of which simply tell the tale. The best of those reconstructions are two Made-For-TV movies, both called Helter Skelter, after Manson’s mad eschatology (briefly: he believed The Beatles had predicted a race war called ‘Helter Skelter’ on the White Album and the murders were his attempt to precipitate this. Many drugs had been taken by this point.)

The first Helter Skelter (1976) concentrates on the trial (it’s based on a book by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi) and Steve Railsback plays the accused. The second (2004) rewinds to show more of the backstory; Jeremy Davies takes the lead here and could be said to be definitive, getting as close to the twitchy zealot as most of us would want to be. The only trouble is he’s too tall: the real Manson was only a notch over five feet.

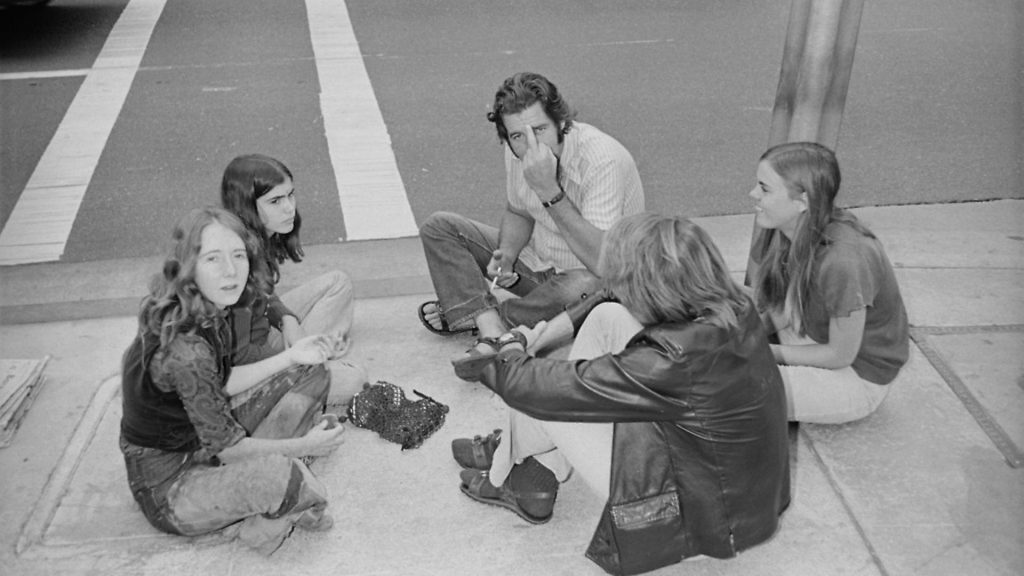

Like most true crime inspired work, the Helter Skelters are an attempt to understand what happened. Only, the Manson killings are more inexplicable than most: it’s not just celebrity that makes them so notorious, nor even the savagery with which they were committed. There’s a strange group dynamic that most of us cannot begin to fathom – Manson himself only gave the orders; his acolytes held the knives, and willingly.

It’s this that’s most fascinated filmmakers. In the last year alone we’ve had Bad Times at the El Royale – where a barely disguised Family makes bad times even worse – and Mandy, in which a failed folk musician, cult leader and LSD enthusiast – the visuals are awash with lysergic madness – bothers Nicolas Cage.

Best of all is Martha Marcy May Marlene, from 2011. As with Emma Cline’s much-liked The Girls, a novel from a couple of years back, it’s a fictionalised representation of the family, with particular attention paid to the young women. The main character is Elizabeth Olsen’s Martha, and it follows her dealings with a commune under the spell of an oddball guru (played by John Hawkes). We’re asked to consider the power relationships of this environment, and its attraction for fragile souls like Martha (and, by extension, the Manson ‘girls’).

But the subject isn’t always treated so respectfully. In mid-1970, before Manson and his followers had even come to trial, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls was released. It had little to do with the film it was notionally a sequel to (that’s Valley of the Dolls) and instead plays out as a parody of a cautionary tale about the dangers of Hollywood, indulging every last fear conservative midwesterners might have held about Sodom-by-the-Sea, complete with drugs, perversion and exploitation.

Naturally it concludes with a massacre that can only be inspired by the then-still-recent murders (something that’s more than a little tasteless, given Sharon Tate had appeared in Valley of the Dolls).

Further proof Charles Manson had become the bogeyman of choice and a lightning rod for hippy haters came in The Omega Man, in which Charlton Heston faced down a vampire cult called ‘The Family’.

Maybe the most lasting influence that Charles Manson had on Hollywood is the hardest to observe.

Whether or not everyone who claimed they had been invited to the Tate residence were telling the truth – “If all the people who were supposed to have been there that night, it would have rivalled [the] Jonestown [massacre],” deadpanned humourist Buck Henry – everyone in the biz began spending small fortunes on security they’d never thought to bother with before.

The shutters came down and the movies reflected this. As has often been remarked, the dominant mood of American cinema in the early 1970s is paranoia. It would be wrong to ascribe that to Manson alone; he struck as the first flakes of what became a blizzard of cocaine – a substance not conducive to a calm, well-balanced worldview – were wafting into Hollywood. That, though, merely amplified what was already there; people were looking over their shoulder, a climate that gave birth to things like Klute and The Long Goodbye and many – many – others.

The highest point of this was Chinatown, one of the great accomplishments of 1970s film and an intimate, if discreet, response to the Manson killings; it was written by Robert Towne but directed by Polanski, back in Los Angeles for the first time since 1969. The script was reworked, the happy ending ditched. Darkness wins, a man’s shot at happiness gets snuffed out. A beautiful blonde dies senselessly.

The Manson killings have impacted pop culture more than any other crime except those of Jack the Ripper. For a man like Manson – who, after all, came to LA pursuing fame – it must have been profoundly satisfying; he might not have been bigger than The Beatles but his death in 2017 was still front page news. Depressingly, a Hollywood story to

the last.

– Charlie Says is available to buy now on YouTube; Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood is released on August 15

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37