STEVE RICHARDS, the veteran chronicler of prime ministers, pinpoints the deficiencies that doomed the man who enabled Brexit.

David Cameron is back and he returns after more than three years of near silence with his familiar public voice, the one that he deployed as leader and prime minister. In his autobiography and accompanying interviews he is conversational, self deprecating, humorous, partially apologetic and defiant.

In other words he follows the model of Tony Blair, as he did as a leader. Unique amongst modern prime ministers Cameron is a shallow impersonator of a previous occupant of Number 10. The shallowness is as illuminating as the attempt to emulate a genuinely authentic leader.

Cameron is in the spotlight again because he finally launches his memoirs, much postponed in the foolishly forlorn hope that the Brexit trauma might have passed by the date of publication. The timing is characteristically misjudged. The book is out at the latest unruly peak of the Brexit saga.

Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings rule chaotically, Tory MPs are kicked out of the party, and the question of whether and in what form the UK leaves the EU is still unresolved.

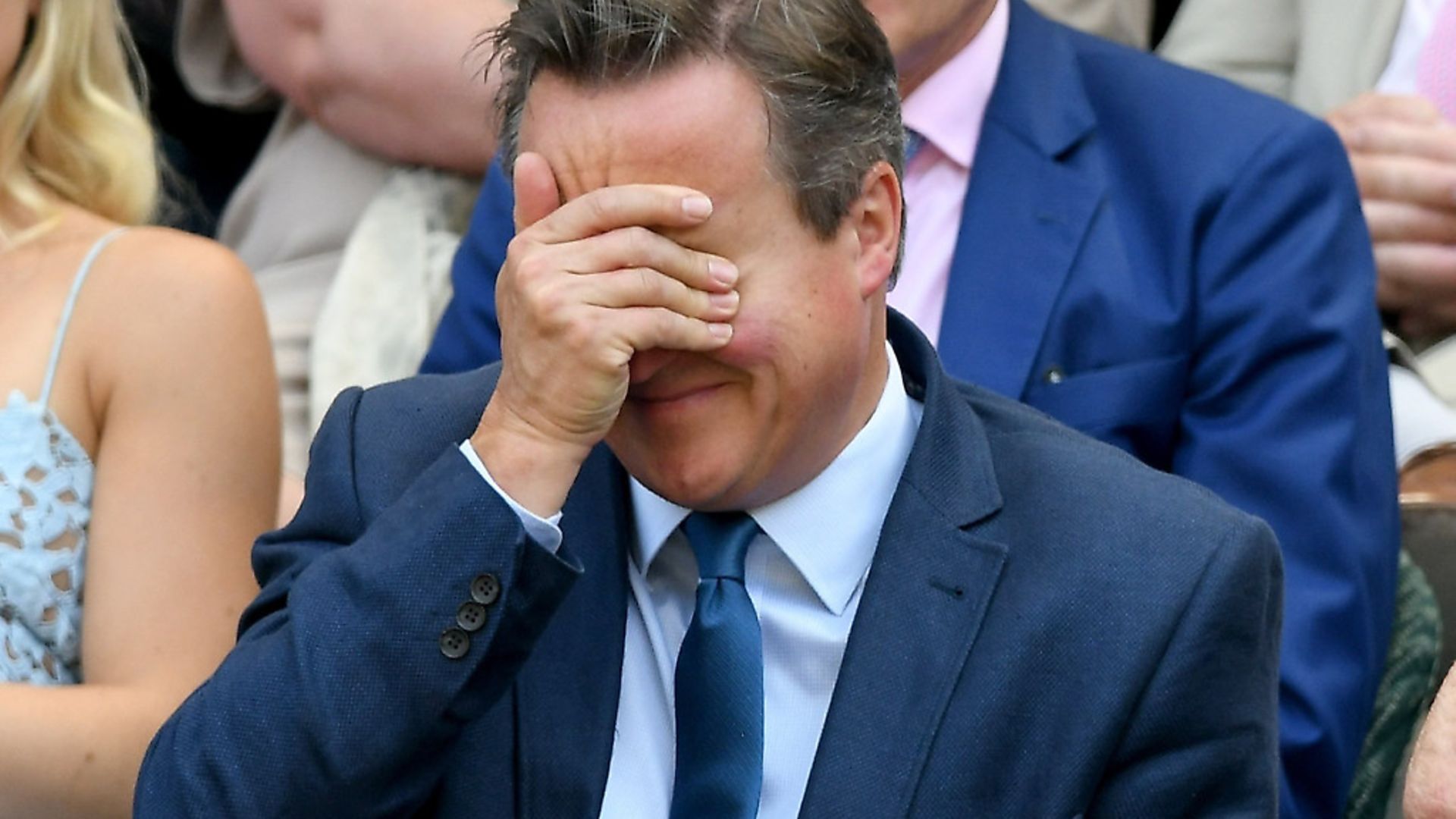

Like Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther films Cameron pops up in the midst of violent political storms, tempests that he triggered, to give his version of events. If he had hoped to unveil his book in an oasis of post-Brexit calm here is further confirmation that he is a poor reader of the political rhythms. Cameron should have waited until around 2030 for his publication date if he had wanted to escape the consequences of his own decisions.

There are precise echoes of Blair in Cameron’s handling of the new book. Blair gave the money for his autobiography to charity. Cameron is doing the same. When it comes to the calamitous, wrecking referendum Cameron tries to do what Blair did in relation to Iraq.

Blair argued before his book, in the book and subsequently that the invasion of Iraq was “the right thing to do” but accepted some mistakes were made in the execution of the war and in the aftermath. Cameron suggests in relation to the Brexit referendum “on the central question of whether it was right to renegotiate Great Britain’s position with the EU and give people the chance to have their say on it, my view remains that this was the right approach to take”. He apologises for several mistakes and miscalculations but the referendum was, in that Blairite phrase, the right thing to do. Above all, Cameron suggests that a plebiscite was inevitable at some point.

This is disingenuous nonsense. There was little clamour for a referendum when he called one in 2013. Indeed the EU was low down the concerns of most voters. Cameron offered the referendum because he was worried that a significant number of Conservative MPs would defect to UKIP and that large numbers of Tory supporters would vote for Nigel Farage’s party at a general election.

On the surface he had a case. UKIP was performing well in elections and two Tory MPs defected in 2014. But for solid reasons a more substantial leader would not have followed Cameron’s course. UKIP was flaky, wholly dependent on the charisma of its leader Nigel Farage.

When Farage resigned after the referendum the party came close to collapse, electing one wacky leader after another. Farage showed the limits of his depth by walking away after winning the referendum. Farage and UKIP could and should have been taken on.

In spite of Cameron’s contorted efforts there are no parallels with Blair and Iraq. In supporting the wildly divided US administration Blair took the wrong course with dark consequences, but the war would still have gone ahead if he had stepped away. In contrast there would have been no referendum but for Cameron.

In addition, the Remain campaign was always going to struggle to win over some Labour voters given the turbo-charged Thatcherism of Cameron’s economic policies. From 2010, there were substantial real terms spending cuts, a level of austerity that had never been considered by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

Partly as a result of his economic policies, far removed from the “compassionate Conservatism” he sought to personify, a significant number of voters felt ‘left behind’ and wanted more ‘control’ over their seemingly powerless lives. This had nothing to do with the UK’s membership of the EU, but Cameron gave them the chance to give him and ‘the elite’ a bashing and they took it.

Cameron’s attempts to be a Tory version of Blair were always shallow. He claimed to be a moderniser and yet on the issue of Europe, the policy area that had torn his party apart, he made no attempt to move on from the recent past.

Instead, during his victorious leadership campaign in 2005 he sowed the seeds of his terrible fall. In order to woo hardline Eurosceptics he pledged to withdraw his party from the centre-right grouping, the EPP, in the European parliament. His press secretary at the time, George Eustice, subsequently a Brexiteer, is convinced Cameron was sincere in his commitment, that Cameron was in many respects a Eurosceptic.

Conversely Ken Clarke is equally certain that Cameron made the pledge solely to secure more votes in the leadership contest and did not believe for one moment that leaving the EPP was the right move.

The conflicting interpretations are further evidence that Cameron was an ambiguous leader rather than one with a sense of modernising mission. He was not remotely Blair-like in his determination to challenge his party. On the contrary he sought to appease the hardline Eurosceptics from the beginning, either because he sometimes agreed with them or out of expedient timidity.

His course was set. The German chancellor Angela Merkel was furious with the decision to withdraw from the EPP. Cameron assumed he could charm her and other EU leaders. This was as much a miscalculation as his assumption that Michael Gove would back Remain in the referendum because they were good friends. The possibly that Gove might have unyielding convictions did not cross his mind.

Cameron was the least developed of modern prime ministers. Like Blair he had never been a minister. Unlike Blair he had limited experience of internal party battles. He had been shadow education secretary briefly and then became leader. He was sharp enough to know his party had to change to become a vote-winning force, but he failed to read the scale of the task when he became leader in 2005.

The party had been slaughtered in three elections and yet under William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard had not greatly changed. When Blair became Labour leader in 1994 there had already been significant internal reforms under Neil Kinnock and John Smith.

Blair and Gordon Brown went further but already Labour was virtually unrecognisable from the party that had been slaughtered in 1983 and 1987. The Conservative Party that Cameron inherited was more of less the same as the one that had been virtually wiped out by Blair in 1997.

If he had been a genuine moderniser he would have gone well beyond his socially liberal reforms and challenged his party over Europe and its obsession with a smaller state. Instead he sought to please his hardline Eurosceptics and was a greater believer in a smaller state than Thatcher had been. Brought up politically in the 1980s, he was not ready to change his party partly because he was not ready to reconsider his own views on economic policy and the role of the state.

Cameron’s memoirs reveal another dimension that is unexpected. He was unavoidably inexperienced as a prime minister but he did not appear to be naive. Yet his apparent surprise at the conduct of Boris Johnson and Michael Gove during the 2016 referendum is simplistic. He seems taken aback that Gove reneged on his pledge to keep a low profile during the campaign and that both pressed mendacious populist buttons. What did he expect? If a binary referendum is called the subsequent campaign is not going to be an objective adult education course.

Campaigns are brutal political battles. Gove could never keep a low profile once he declared in favour of Brexit. Both of them were bound to fight crudely and without great interest in the truth. They are not alone. This is what happens in campaigns and always has been. The mistake was to call a referendum on an issue of such multilayered complexity.

Cameron was and is a decent human being, a right-wing Conservative, socially liberal, with a streak of Euroscepticism, who also calculated that the way to win was to copy Blair and New Labour.

He tried to do so but without depth or ideological verve. As a result he did not win a majority in 2010 and only just secured one five years later. At some point the Conservatives will elect a genuine One Nation Tory. While Johnson is expelling Thatcherites like Philip Hammond and Oliver Letwin that moment is a long way off.

Steve Richards’ latest book The Prime Ministers: Reflections on Leadership From Wilson to May is published this month

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37