In the 1940s, the Santa Monica house of the Austrian actress and screenwriter Salka Viertel and her screenwriter and director husband Berthold, became a literary and artistic salon for a community of exiled writers, artists, thinkers and scientists, who had all fled from the Nazis.

Visitors to the house included many of Weimar Germany’s leading cultural and intellectual figure; Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, F.W. Murnau, Schoenberg, Billy Wilder, Adorno and Bertolt Brecht were all visitors to the Viertels’ Sunday afternoon salons. As Europe tore itself apart, Los Angeles, out on the edge of the Western world, became one of the last outposts of Weimar culture.

Germany’s Weimar Republic was born in August 1919 amidst the fall-out of defeat in the First World War and the subsequent failed communist revolution. It ended in January 1933 with the appointment of Hitler as Germany’s Chancellor. Between these two dates was a period of catastrophic political instability, in which a succession of 14 chancellors, and the 20 governments they formed, were unable to deal with the terrible economic stagnation, the absurd levels of inflation, the violent political extremism and the ideological consequences of Germany’s defeat in 1918.

The political disaster of Weimar is as familiar a story as the contrasting tale of the period’s cultural life. In literature, cinema, art, philosophy, academic political theory, music, theatre, in sexual politics and in the demi-monde world of night-clubs and cabaret, Weimar was an extraordinary age. During these years, Germany – and Berlin in particular – became the centre of the avant-garde. Writers, artists and thinkers tore into the question of what it was to be modern, and what modernity meant.

It wasn’t a ‘flowering’ or a ‘Golden Age’ as such; these phrases suggest something wholesome and healthy. It was the antithesis of those qualities; something more associated with weeds and rust perhaps. It was a culture that was born out of what was essentially civilisation’s collapse during the First World War. As such, it was a culture that confronted alienation, fragmentation, psychological sickness, damage, defeat, loss and violence. (It was also a culture that got stuck into sexual freedom, hedonism and a robust individuality – so it wasn’t all bad).

And then in April 1933, this high-point of artistic modernism, was smashed to pieces. When, after the Enabling Act of April 1933, the Nazis seized absolute power they wasted no time is eradicating the art and the literature they despised. The first book burning by the Nazis, of Marxist books, took place on April 8. It was followed by the burning of books written by Jews, by liberal critics and by writers the Nazis considered degenerate.

The party had been banning the art they considered degenerate from as early as 1930, when the prominent Nazi Wilhelm Frick, who was serving as the Minister for Culture and Education, ordered the removal of Expressionist art from the Schlossmuseum in Weimar itself, the central city which had been a focal point of the German enlightenment and where the doomed constitution had been drafted after the First World War. After the Enabling Act, this process was intensified. Artists whose work the Nazi considered degenerate were unable to get their work displayed, curators sympathetic to modernism were replaced by Nazi functionaries. Hitler, who had failed as an artist, turned his personal opinions about art into state policy.

And as the functionaries were removing art from galleries, and removing academics from their posts, and while Nazi thugs were burning books in town squares, many of the writers, artists and intellectuals fled. The Weimar culture – this high-point of European artistic modernity – simply shattered. The exiles fled to wherever they could be safe, with many ending up in the USA. Both New York and Los Angeles became the last outposts of Weimar culture; Weimar on the Hudson and Weimar on the Pacific.

One of these exiles was the artist Josef Scharl who left Germany in 1935 and is currently the subject of a retrospective at Bremen’s Paula Modersohn-Becker Gallery.

Much of this Weimar ‘weeds and rust’ culture can be seen most clearly in Weimar art, especially in the style of art known as the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a school of art that included. This art grew out of German Expressionism, but it was also, simultaneously, a reaction against it.

German Expressionism originated with two groups of artists: Die Brucke (‘the Bridge’), based in Dresden and Berlin, and Der Blaue Reiter (‘the Blue Rider’), based in Bavaria. Establishing themselves in the years before the First World War, these two groups did so much to place German art in the avant-garde. Their art of simplified forms and vivid colours reflected their place in what they saw as a troubled age, an age where a younger generation wanted to cut through dull, tired bourgeois certainties. They wanted something more heroic and honest and radical.

Except, of course, it wasn’t that troubled an age, especially compared to what came next in the killing fields of Flanders. The romantic radicalism of Die Brucke and Der Blaue Reiter seemed a bit absurd and self-absorbed after that conflict. (Artists involved in both groups served during the war. Some were killed, others experienced terrible psychological traumas). And then, in the years after 1918, the political upheavals, the violence of political street fighting, the economic chaos and social inequality did their part in convincing these artists that self-absorption was self-indulgence. And that’s why it was replaced by the Neue Sachlichkeit. Many of the artists, most of whom had started out as expressionists, rejected that expressive romanticism and instead committed themselves to trying to describe this new shattered, broken, Germany.

Sharl is typical of the German artists of this generation. The starting point with his work is his indebtedness to Van Gogh (a bit too indebted some might argue). It is very clear in his earlier work, in paintings such as Vertreibung aus dem Paradies (‘Expulsion from Paradise’) and Landschaft mit drei Sonne (‘Landscape with Three Suns’) and is concerned with a romantic search for metaphysical or spiritual truth. But this expressionism in Scharl’s work is gradually replaced with portraiture of the rural and urban poor and the marginalised. His art goes from something romantic and spiritual to something engaged with the difficulties of the times in which he lived.

Two works stand out in this exhibition. The first is the Blinder Soldat (‘Blind Soldier’) of 1928. This painting is of the legacy of militarism and the brutal affront to human dignity that war brings. It is also a painting of an unseeing and lost individual. It is a painting that carries so much of the spirit of Weimar Germany – the legacy of the war, the damaged individuals, and the inexplicable – unseeable – nature of modernity.

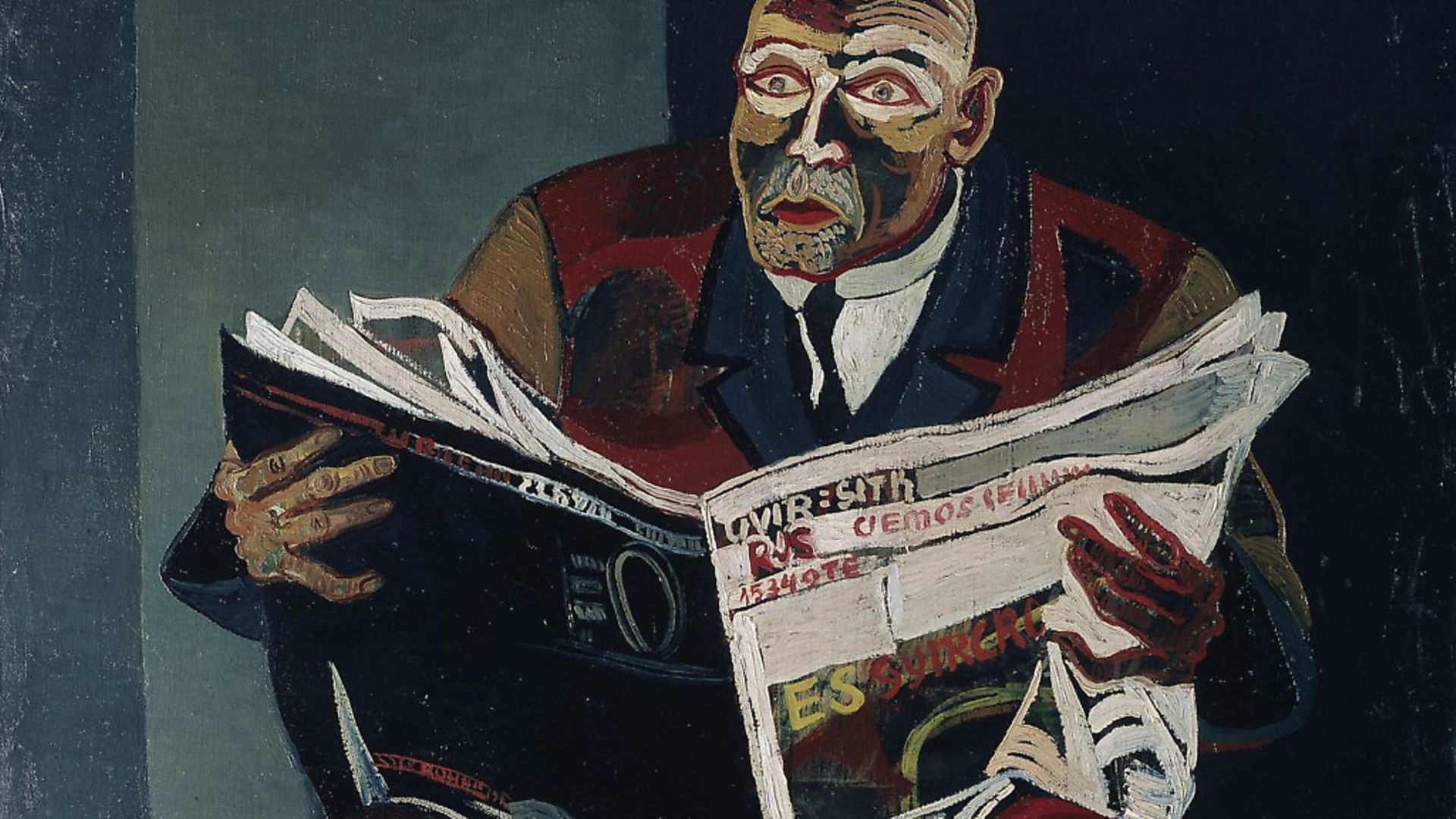

The second is Der Zeitungsleser (‘the Newspaper Reader’) of 1935. Painted after the Nazis took power, it shows a man terrified of what the world has become. It oozes fear. In this painting, this inexplicable nature of Weimar modernity has become the terror of fascism.

Alongside this terror, Scharl’s post-1933 art descends into the grotesque; we see skinned animals with their feet chopped off, corpses, bloated hairless nude figures. Something emotionally expressive had returned to his work and what it was expressing was the horror of fascism.

Scharl is a largely forgotten figure in German art, and his career has always been overshadowed by the giants of the Neue Sachlichkeit; Otto Dix, George Grosz and Max Beckmann. In 1935 Scharl escaped Germany using a connection he had with Albert Einstein – he had painted him in 1927. Einstein vouched for him, and Scharl got to New York. In America his art lost its focus somewhat, and whilst he did get some commissions (and became friends with Einstein) his career faded. He died in anonymity in 1954.

However, this exhibition succeeds in showing how Scharl mapped so much of the psychological terrain and social dynamics of the Weimar years and its usurpation by the Third Reich. This exhibition charts a world of fear, alienation and violence. It shows us the legacy of militarism, the brutality of class differences and the role of the press as part of mass culture.

And this brings us back to that California outpost of Weimar culture – because all of these things were at the centre of so much of what was discussed in those Santa Monica salons.

This Weimar exile culture was most concerned with two questions. The first was why the communist revolution in 1919 had failed. The First World War was widely understood as being a capitalist war in which the working classes had been slaughtered in their tens of thousands. If communism was ever going to seem like a viable alternative to capitalism, and to the interests of the industrialists and the imperialists in Germany, then 1919 was when that was going happen. But it hadn’t. Moreover, the communists and the socialists were unable to gain enough votes or political traction to provide any stability in the Weimar years. Finally, the German people (though never with an overall democratic majority) had turned to the fascists, rather than the left, for salvation from capitalism’s chaotic excesses.

Between 1914 and 1945, history felt as though it was something that was imposed on the mass of ordinary German people. This image, of the ordinary man and woman as a bewildered victim of things beyond their control, is something that you can see in so much of Scharl’s art. His portraits feature people who, in their resigned, worn out gaze, seem to carry the weight of an indifferent world.

Marxism is essentially an argument that the working classes should no longer be subjected to history – that the world stops being something that imposes itself, often unfairly and occasionally violently, on their lives. The question for German Marxist intellectuals in Weimar Germany was why the working class had failed to seize their moment in 1919.

This was the question that the Frankfurt School was confronted with. This was the name given to the group of neo-Marxist intellectuals, who were initially connected with the Institute of Social Research at Frankfurt’s Goethe University. Key figures associated were Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse and Walter Benjamin.

When the Nazis seized control, their first sustained assault was on the left. Socialists, communists, trade-unionists and liberals were rounded up and held in Dachau – the prototype of what became the Nazi concentration camps. At this point, Dachau wasn’t a death camp – though people were beaten to death as scores were settled – but it was clear that Nazi Germany held no future for left-wing activists and Marxist intellectuals.

Using connections in academia, and support where they could find it, the various intellectuals associated with the Frankfurt School, along with thousands of other Jewish or left-wing academics, all fled Germany. Most of the Frankfurt School made it to the USA. Tragically, Walter Benjamin failed.

Benjamin was the most original of all the thinkers and writers associated with the Frankfurt School. His worldview was a mixture of Marxism, Judaism and modernism. His dense and complex prose style, carried within it the force of history and the full scope of experience, whilst simultaneously questioning what history and experience meant. As such it is almost impossible to categorise his writing and his life’s work – there is something almost poetic in the way he teased out the contradictions in his philosophy and his critical thinking. This can be seen in what is probably his most famous aphorism: ‘There is no document of civilisation that is not also a document of barbarism.’

He was everything the Nazis hated, not just because he was Jewish, Marxist, and an intellectual, but also because he was someone who existed beyond the Nazi imagination. His inner life and his imagination – fluid, critical, contradictory – meant nothing to the dull-witted thugs unable to conceive of anything beyond their desire for order, and for power over life – and death.

Benjamin got as far as Spain, but was informed by the Spanish authorities that he was to be returned to Germany. He committed suicide (the people he was travelling with were allowed to leave the next day). His brother Georg would be murdered in the Mauthausen–Gusen concentration camp in 1942.

Adorno, Horkheimer and Marcuse all made their way to the USA, where they continued their work at trying to make sense of why the revolution of 1919 had failed and why fascism had triumphed. It is impossible to summarise their arguments in this article in anything other than in the broadest way, but much of their thinking comes down to them trying to understand the ideological methods by which capitalism legitimised its control.

Perhaps the most graspable concept associated with the Frankfurt School comes in the book Dialectic of Enlightenment, written by Adorno and Horkheimer and published in 1944, in which it is argued that mass culture – film, radio, magazines – works to keep the masses docile. Depending on how you see the masses, this insight is either a brilliant critique of how power works in a modern industrialised nation or a sneering elitist view of the masses as idiots.

The other question that confronted the exiled Weimar community was the question of whether the evil at the heart of fascism was somehow an inherent part of German culture. The argument took place between two of the most high profile of the exiles: Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht.

Mann was Germany’s best-known novelist; he had won the Nobel Prize in 1929. His success began with his 1901 novel Buddenbrooks, which traces the decline of a powerful Hanseatic merchant family from Lübeck between 1835 to 1877. It was a publishing sensation in Germany, its success having much to do with its being an intimate description of how the country came into being in the 19th century. It was a beloved novel that became tied up with Germany’s sense of itself.

There is much more to Mann than his being the great literary chronicler of Germany – but this is a big part of his reputation. Somewhat effusively, he has sometimes been called the guardian of Germany’s soul. His novel, The Magic Mountain, is one of the major literary works of Weimar literature. It is a novel about the collapse of both reason and of European civilisation; it is also about time and history, and raises fundamental questions about how fiction and reading work. (It is a tough read).

Mann escaped the Nazis in 1933. Warned by his children not to return from France where he was staying, he made his way to Switzerland. In 1939 he travelled to the US where he taught at Princeton (Einstein was there at the same time). In 1942 he moved to Los Angeles, where he remained until 1952. He was one of the most high profile German figures outside of Nazi Germany – his role, at times, seemed almost leader-like among the exiles.

Despite this vaulted status as the voice of Germany’s conscience, Mann was not prepared to let Germany off the hook. He saw the Nazis as something inherently German; as being a product of Germany. That excess of emotion, of will, of drama that characterised so much of the Nazi’s sense of themselves, was something he traced back through various German intellectual traditions; through Wagner and romanticism and back to Goethe and Schiller. Mann saw the Nazis not as being evil Germans who had defeated good Germans. He saw them as being essentially German.

Bertolt Brecht disagreed.

He was a Marxist playwright and poet (and closely associated with the Frankfurt School; Walter Benjamin was a friend). In 1925 he had arrived in Weimar Berlin and immediately saw how the Neue Sachlichkeit could be applied to theatre. He developed a theatrical language that emphasised the function of theatre production. There is nothing immersive or distracting in Brecht’s theatre – you really can see the working of drama. As such it was an approach that made the audience hyper-conscious of what they were seeing and, therefore, thinking.

In 1927, he began his collaboration with the composer Kurt Weill. They wrote a series of successful musical dramas, the best known of which was Die Dreigroschenoper (‘The Threepenny Opera’).

In 1933, Brecht fled Germany, making his way first to Scandinavia (where lots of the German left escaped to) and then, in 1941, to California. Brecht’s disagreement with Mann, which became quite vitriolic, had much to do with his Marxism.

Brecht saw fascism as being an extension of the interests of capitalists, industrialists, the Junker Prussian aristocracy and imperialists; and these interests came at the expense of those of the working class. In other words, you have good Germans – the proletariat – defeated by bad Germans – the fascists. Brecht’s position in this argument was that of the Soviet Union’s.

The USSR had allowed German exiles who had fled to the east to establish the National Committee for a Free Germany. By ‘Free Germany’ the Soviets meant the German working class liberated from fascism. It can be assumed, because of what happened after 1945, that this liberated Germany would then fall under Soviet control.

Brecht could be myopic when it came to Stalinism and the USSR – after the war he settled in East Berlin (as did a lot of people from the theatre and the arts; they were heavily subsidised and could enjoy a privileged position). But this pro-Soviet myopia does not mean that his good Germans/bad Germans thesis was erroneous. It is obvious to state that the Nazis could only gain control in Germany through the violent coercion of their enemies. Lots of Germans died because they stood up against the Nazis. There were good Germans. Brecht was correct about that.

But Mann was not alone in thinking that there was something inherently rotten in Germany, which fascism grew out of. Mann’s last novel, Doktor Faustus, was concerned with that very subject.

This work owes so much of its existence to exile Weimar culture in California. As the title suggests, it is a reworking of that ancient German Faust myth which was also the basis of Goethe’s work Faust. It is the story of a composer, Adrian Leverkühn, and his search for artistic greatness, in which he embraces madness (he deliberately contracts syphilis). This is Leverkühn’s pact with the Devil.

To write the novel Mann relied on Adorno’s help in making sense of modern avant-garde classical music – something that Adorno understood and had written on. This was the 12-tone technique as invented by fellow LA exile Arnold Schoenberg. This music was a shift away from the traditional use of tonal harmony that was central to the Western Classical tradition. Harmony suggests resolution; the 12-tone system suggests atonal dissonance and something fragmented.

Leverkühn is driven to go beyond harmony and beyond reason and beyond the human in pursuit of genius. This places him in the tradition of the romantics: of Goethe and Schiller, Beethoven, Wagner, Nietzsche and perhaps of Mann himself. In this view of German art, the human is denied, in the pursuit of greatness. This, according to Mann, is the inherently German thing and that allows for fascism.

And this brings us back to the exhibition of Scharl’s work. There is, in Scharl’s later paintings, something monstrous and deformed. His reaction to fascism is that the human becomes lost. Something monstrous replaces it. Scharl’s painting echoes Mann’s novel.

The legacy of Weimar in exile is almost impossible to measure. As the true horror of the war become clear, it became obvious that humanity now had a secular measure of absolute evil, a measure that didn’t need to find its gauge in metaphysics or myth or spirituality, but could instead be seen in the buildings and railways lines of Auschwitz, in the burnt remains of the dead in Hamburg and Dresden and the mushroom clouds at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The first people to describe that secular measure of absolute evil were the Weimar exiles.

But in post-war Germany, this horror was greeted with what was almost silence. Few of the Weimar exiles returned and very few artists and writers appeared in post-war Germany to take their place. Scharl’s story – of his drift into silence, is not atypical. Mann’s vision, that the Nazis came out of something inherent in German culture, was something that was felt throughout the country in the post-war period. As such, in many ways, huge parts of German culture just shut down. Confronting what happened between 1933 and 1945 would not really occur until the 21st century.

However, the Frankfurt School’s influence on the post-war political imagination was massive. The books of Adorno, Horkheimer and Marcuse formed much of the basis of the politics of the New Left – those baby boomers, whose anger at their parent’s generation for what happened between 1939 and 1945 found a focus in the anti-Vietnam War demos of the 1960s. (These activists also raged at Adorno who infamously always put theory over practice. In the 1968 protests he refused to leave his classroom).

And their political analysis is still relevant today in a world of fake news, where it is argued by some that Facebook memes can influence elections. How the world is and how we see it continues to be one of the central questions at the heart of politics.

It is hard to think of any other time in history when a whole artistic and intellectual culture, as rich and complex as that of Weimar Germany’s, just decamped to somewhere else. What it then did, whilst in exile, was to act as the conscience of a world that was plunged into horror. Mann and Brecht, Benjamin and Adorno – and the largely forgotten Scharl – were all part of this process. They constituted, at least at the level of ideas, a profound counterpoint to the Final Solution and the Third Reich.

The Josef Scharl exhibition runs at Bremen’s Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum until June 3

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37