There is one sure fire way to tell if a problem is a politically impossible one in the United Kingdom: count how many times the government has commissioned a consultation – or worse yet, an independent review – into it.

According to the BASW union, successive UK governments have, since 1996, commissioned seven policy papers, five consultations, and four independent reviews into social care.

Cynics might suggest the UK has kicked the can down the field for 24 years, but surely all those reviews and consultations have at least one thing going for them: the current government, which was elected with a pledge to fix social care, must have a programme to do so…

That plan was revealed in last week’s Queen’s Speech. On social care, a manifesto pledge and one of the major long-term challenges facing the nation, Her Majesty announced: “Proposals on social care reform will be brought forward.”

Any hopes that the monarch had skipped the key details by missing a paragraph or some such were dashed. When it comes to deciding how to fix the system that’s supposed to care for us in our old age, or as a result of disability or long-term sickness, we still have nothing more than vague promises, for the moment, after 24 years of letting things get worse.

All four nations of the UK are facing similar challenges with social care, but the systems in each are devolved and the details different. The overall ‘problem’ is, in a sense, one of prosperity – more people are living for much longer than they used to.

One issue is that on average quite a lot of those ‘extra’ years are lived in poor health, needing either help and home, to live in residential care, regular hospitalisation, or some combination of the three. All of these are expensive, especially if we want to pay the people delivering it better, as polls suggest we do.

Compounding this is that there are fewer working age adults per pensioner than there used to be, thanks to falling birth rates – meaning that there are fewer people paying into the system for each pensioner.

As with pensions, there is no ‘pot’ of savings to fund social care – today’s taxpayers cover the cost of the state pension and of social care. The tax current pensioners paid in was spent long ago.

Exacerbating the problem still further is a disconnect between the NHS and the providers of social care – who are generally funded by local government, rather than by the health service. That can create awkward incentives for both, especially when they are under sustained financial crisis after years of cuts or restricted budgets.

The result in England at least is a social care system that only has the state stepping in for people with very little in the way of assets – certainly not anyone who owns their home – with quite a strict taper on sharing the payment. The result is people selling cherished homes to pay for care.

But so toxic is the issue that when Theresa May proposed a mechanism to fix it – a policy to shift the sale of the house until after the death of the person needing care – the plan was immediately dubbed the “granny tax” and is widely credited with costing May her majority in the 2017 general election.

The UK, though, is hardly the only nation facing a social care crisis: most of the global north is confronted with the exact same set of problems – of an aging population, a comparatively smaller ‘adult’ population, and less in the way of informal care networks from extended family. So are there lessons to be learned from overseas?

To those who enjoy uniquely British stories of failure, or particularly easy answers, the evidence seems to suggest nowhere has entirely solved the problems of social care – but lots of places try to manage things very differently to the UK.

But some of the similarities are striking: a recent study across several major economies looked into the idea that families in the UK provide less informal care than our European neighbours do – a common explanation presented for the UK’s problems, and one that handily shifts the blame onto families, especially women. But this turned out to be a myth – British families provide about the same amount of informal care to their loved ones as our international counterparts.

Perhaps surprisingly, the study also found that UK public spend on social care was not especially low by international standards. Despite it requiring large payments from many families to contribute to the costs, the UK still spends slightly above the OECD average.

So, neither the explanations of our government trying to do it on the cheap nor our younger generations being unwilling to do their bit explains our problems – at least not in full.

What was very different, from country to country, was how social care was paid for and what the services look like once they’re delivered.

Some countries work like the UK, with the public funding portion of social care coming from general taxation.

This is the case in Italy, where social care is funded from local or regional taxes, with a measure of top-up from central government. Italy’s system is much more relaxed and much more decentralised than ours – often simply handing out cash to the families of elderly people in need of care, and doing very little to check up on what they do with it.

Many families choose to directly hire in unqualified home help, who have no training requirements. The result is a simple system that often provides a key lifeline to families – especially in Italy’s poorer regions – but with little to no visibility on the quality of actual care provided to the people who need it.

Spain similarly funds its system from general taxation and provides a lot of its services in the form of a cash contribution – but does provide some services too, albeit with a co-payment assessed on income. Safeguards, of modest effect, include making the transfer in the name of the person needing care, rather than their relatives, but the social care system has been chronically underfunded for more than a decade following post-2008 cuts.

Other countries have systems of social insurance – which create specific earmarked funds to pay for social care, insulating the system from general government spending cuts. While the UK has National Insurance, in practice in modern times this just enters general taxation, and is not earmarked or protected in any way.

Germany has a small national insurance-type tax – split between the employee and employer – that charges a premium for childless adults who are likelier to have more social care needs, and unlike the UK also requires pensioners to pay a contribution.

This spending is earmarked for social care, which then requires a means-tested co-payment, albeit on a smaller scale than in England. Unlike virtually every other system, Germany’s seems sustainable: it has run surpluses in multiple recent years.

France also has an insurance scheme, but requires smaller co-payments on average, with analysis showing it has one of the most progressive social care systems of many major economies – but it isn’t in the same financial good health as Germany’s, facing shortfalls of its own. The richest pay 90% of the cost of their care out of pocket – the poorest pay nothing.

For a country with a notoriously aging population, Japan’s social care system is not years ahead of the rest of the world – in fact, it had to cut any support for accommodation costs as far back as 2005, because it had simply become unaffordable.

Japan funds its system from a mixture of general taxation, a social insurance contribution from older working age adults, and requires a small co-payment from everyone, regardless of income.

Overall though, no study of countries seems to find one true model or one true fix – paying for social care is a problem facing almost every wealthy country, and none of them seem to be rushing to fix it.

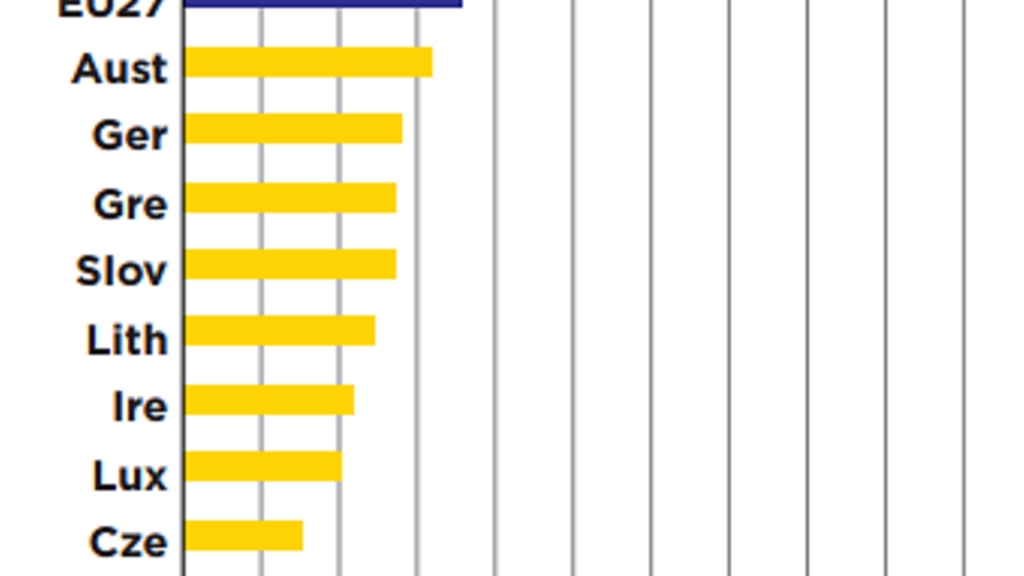

Inevitably – as is so often the case with public services – the best of the bunch seem to come from the Scandinavian countries, notably Sweden. But there doesn’t seem to be any particular trick that the country has discovered that others haven’t – rather than having some magic fix, Sweden quite simply spends more than other countries. Much more: Sweden spends roughly twice as much of its GDP on social care as we do in the UK.

Boris Johnson has promised to tackle social care this year. But this isn’t an issue that’s prone to waffle, or clever tricks – it needs serious money. Is his Conservative Party capable of taking serious action?

POLITICS’ INTRACTABLE PROBLEM

If everyone wants to know that their relatives will have social care if they need it – and don’t want to lose their own house when they retire – then why is solving this conundrum such a nightmare issue in British politics?

The main trouble comes from the fact that any solution will have losers in the short-term, and will also serve to spotlight how bad the status quo is to people who might not be aware of it.

This second problem is what brought Theresa May to grief when she introduced the “granny tax”. Her proposals gave people a way to make sure they wouldn’t lose their home until they died. But for many people not familiar with the status quo – who didn’t know many have to sell their house while still alive under the current system – it seemed like a bid to steal the homes of the nation’s pensioners.

The simplest way to fix the problem might be just to increase tax: higher income tax, capital gains tax or national insurance would all help tackle the problem without creating any new strange incentives – but most Conservative manifestoes are premised on not raising these taxes, and any change to this would face a swift internal revolt.

Similarly, introducing a new tax becomes something of a non-starter for a Conservative government. But even the organisational fixes are hard: it is easy to suggest we should have a united health and social care system, managed by the NHS.

Councils might even be happy to shed this responsibility, though NHS managers might be less enthusiastic about taking it on. But the numerous private care home owners across the country might be resistant to quite a lot of changes. Every choice has a lot of stakeholders, and every choice will have unpopular aspects.

The result has been every government has punted it to their successor – and so here we are.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37