As a new collection of films by Jacques Demy is released, JAMES OLIVER shows how his colourful and passionate works also reflected shades of grey.

The world would surely be a better place if it was more like the movies. Things would be tidier and more conclusive for a start. And who knows? Maybe people would even burst into spontaneous song and dance routines. When measured against Technicolor fantasias, real life is so often a disappointment, where people who deserve happy endings don’t always get them.

Most of us simply accept this with a shrug, but Jacques Demy found it harder to move on. He was a filmmaker himself and this tension, between fiction and reality, was a theme he explored again and again in his work. Demy was no theoretician: his major films – newly gathered in an essential blu-ray boxset – brim with colour and passion. But look closer and you see a man preoccupied with the gulf between the world as it was and as we might want it to be.

He emerged as part of what became known as the French New Wave (‘nouvelle vague’), a grouping of film lovers turned filmmakers who electrified cinema in the 1960s. Hindsight, though, shows that Demy was an uneasy fit with the movement. While most of the figureheads and leading lights (Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard) had emerged from film criticism, Demy’s background was practical – he’d studied photography, then worked as an animator and assistant director.

Moreover, most of the New Wavers were thoroughly metropolitan. Demy lived in Paris but he was a hayseed next to a former street kid like Truffaut or the upper-crust Godard; he came from Nantes, an unremarkable city on the unfashionable Atlantic coast, where his father had been a mechanic and his mother a hairdresser. His love of movies was born visiting his local picture palace and, despite his later association with Parisian intellectuals, he never quite forgot the giddy rush he got when the lights went down and the main feature started.

Still, it was easy enough to place his debut – Lola (1961) – within the New Wave. As with Truffaut and Godard, Demy did not wear his cinephilia lightly: Lola is dedicated to Max Ophuls (a celebrated director of heartbreaking romances) and its title and plot nods to Ophuls’ final masterpiece Lola Montès. But while Lola Montès was a 19th century courtesan who hobnobbed with composers and kings, Demy’s Lola (Anouk Aimee) dances in a low-rent bar in Nantes, entertaining sailors and breaking hearts while waiting – yearning – for her lover to return and carry her off into the sunset.

It’s full of moments that remind us of other movies – a young man, for instance, a hopeless dreamer called Roland (Marc Michel), becomes infatuated with Lola and gets involved in a criminal scheme that any B-movie gangster would be proud of. But that’s undercut by the sense of regret and loss that pulses through the film that shows us lives messier than the movies usually allow.

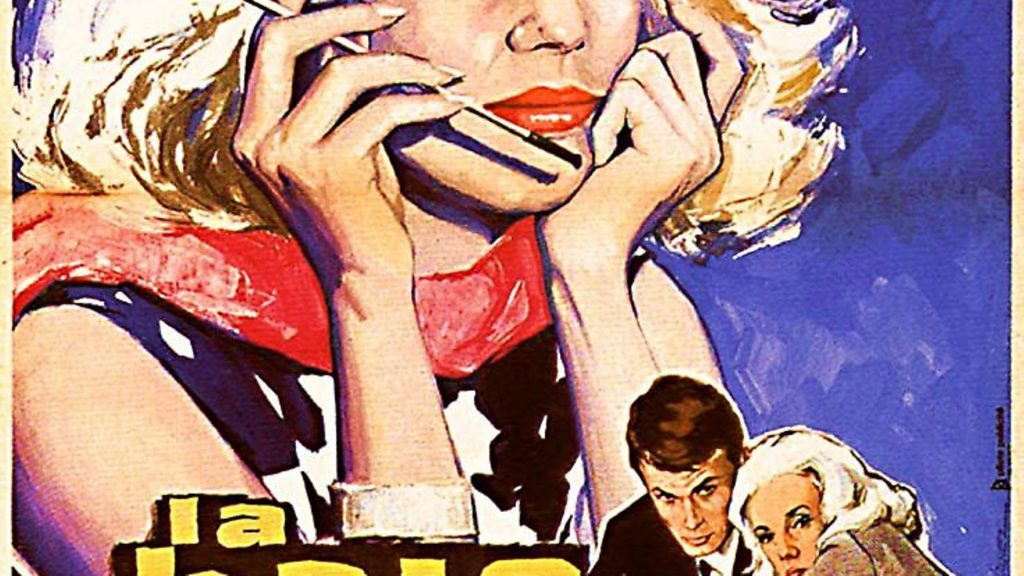

Demy’s next film was also set by the seaside, albeit in more salubrious surroundings. La baie des anges (Bay of Angels) plays out in the casinos of Nice and Monte Carlo. Again, a callow young man falls for a worldly woman – and who cam blame him when she’s played by Jeanne Moreau at her peak? She is a high-rolling gambler and, as the young man brings her luck, he’s welcome in her world until he doesn’t. This is not a realist’s depiction of gambling addiction, but it captures the highs – the hit of a big score – better than anything else and Demy, unlike his characters, knows what the odds of long-term success really are.

Both Lola and La baie des anges were critical favourites and modest financial successes too, but it was his next film that really made his name. When Lola was released, Demy described it as “a musical without music” but he decided he wanted to go further. Working with composer Michel Legrand – a vital collaborator on many films – the director devised a full-length homage to the Hollywood musicals he so loved, with the story told in song not dialogue. Moreover, Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (‘The Umbrellas of Cherbourg’) would not be shot in elegant monochrome but in magnificently gaudy colour.

All this made it a more commercial proposition (that, and the actress Demy cast in the lead: Catherine Deneuve, at the start of a remarkable career). But don’t think Demy was selling out: although the film works – quite perfectly – as melodrama, it’s also his most probing work. No matter that he drew on the conventions of Hollywood cinema – the music, the production design – it’s rooted in a real place: Cherbourg isn’t usually thought of as romantic but Demy’s camera makes it seem as beautiful as it would be to any first-time lover.

Despite all this artifice there’s nothing phoney about the emotions. Deneuve plays Geneviève, a young woman who works in her mother’s umbrella shop and who falls in love with Guy (Nino Castelnuovo). But they are to be parted, in what was then the cruellest way possible. This might be a candy-coloured entertainment but it touches a subject virtually no other French film of the time dared do; Guy gets called up to fight in Algeria, part of the – well, “savage” hardly does it justice – French response to the Algerian independence movement. To mention it in an ostensibly escapist romance was audacious indeed.

But life goes on in Cherbourg. Geneviève meets someone else, a nice chap, and when Guy returns, he discovers that she is married. Once he gets over his broken heart, he marries someone else too. Both relationships are solid (strong enough to survive the brief moment when the former lovers inevitably meet one last time) and everyone is happy enough. It’s just that things aren’t quite as wonderful as once they were. But isn’t that how things usually shake down? It might be as far from “realism” as it is possible to get but no one (except a few lucky souls) can say it isn’t true to life.

(By the way, if anything mentioned above reminds you of recent Oscar winner La La Land then that isn’t a coincidence; Damien Chazelle, director of that film, has called The Umbrellas of Cherbourg “the greatest movie ever made”.)

Demy followed The Umbrellas of Cherbourg with a companion piece, Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (The Young Girls of Rochefort), another musical that finds unexpected glamour in an unloved Atlantic port. But it’s bigger and brighter – to star alongside Catherine Deneuve and her sister Françoise Dorléac, Demy recruited Gene Kelly, star of his favourite musicals. The melancholy of the previous film has dissipated and the mood is more frivolous, gloriously so.

These days, there are many who’ll tell you it’s a masterpiece but it was more coldly received at the time. This was 1967; the mood in France was turning more political and here was Demy making a confection. Things weren’t helped when it was revealed that Demy was off to make a film in America. For all his generation loved American cinema, the US itself was rather less loved in the age of Vietnam.

Still, Demy was determined to go and relocated with his family (he’d married Agnes Varda – a formidable filmmaker in her own right – in 1962). The film he made there was called Model Shop. A more naturalistic film than he had made thus far, it continues the story of Lola, from his first film; she’s washed up in Los Angeles, working as a model for amateur pornographers when she catches the eye of a young man called George (Gary Lockwood), another of Demy’s daydreamers. Lola wants to return to France while George has been drafted to Vietnam; neither is happy but somehow they convince each other to keep going.

A failure on first release (Demy called it “Model Flop”), it’s only grown in stature since; it was a major influence on Once Upon A Time in Hollywood, for instance, and it’s one of the great films about LA. But that appreciation came later: at the time, he returned home to make a fairy tale adaptation called Peau d’Âne (Donkey Skin), a film that even admirers describe as “kitsch”. It was his biggest commercial hit, allowing Demy to indulge his taste for make-believe in subsequent films. Perhaps indulge it too much, in fact: the later work has its admirers but rather more detractors, who find the films lightweight and slightly laboured. Only Une chambre en ville (A Room in Town) (1982), a tale of murder and abuse that’s both a return to musicals and the darkest thing he ever made, captures some of the old magic.

He died aged 59 in 1990, of leukaemia, so it was first announced. Later on, Agnes Varda revealed, actually, it was complications from Aids. Demy was bisexual and had apparently contracted the virus during a brief separation from Varda in the mid-1980s.

But let’s not dwell on his end; he should be remembered and celebrated for the work, which seems greater than ever. For all the moments of sadness in his work, few filmmakers knew how much joy was part of life, and fewer still who could put it on screen so well.

The Essential Jacques Demy is released on February 17 on The Criterion Collection; Model Shop is available on Arrow Academy

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37