Shane MacGowan is a challenging subject for a new documentary film. JASON SOLOMONS talks to its director about a hard to love character and staying the right side of romanticism

With his rotten-looking mouth, pallid grey skin and slurred speech, Shane MacGowan is the alternative face of Christmas.

The Pogues singer and drunken Anglo-Irish poet is widely acknowledged to have written and sung the most popular yet most controversial festive song. No, it’s not All I Want for Christmas (Is My Two Front Teeth) but his pugnacious duet with Kirsty MacColl, Fairytale of New York in which two Irish actors and former lovers wassail late on Christmas Eve, off Broadway, in New York, wallowing in resentment, broken dreams and recriminations but feeling the warmth and romance of Christmas celebrations all around. Before getting arrested.

Just as traditional as its popularity every December – it is officially the most played Christmas song of the 21st century, according to music licensing company PPL, and has been in the UK Top 20 17 times since its first release in 1987 – is the annual controversy around the song’s lyrics, particularly the use of “old slut on junk” and the word “faggot”, which the BBC seem to re-edit or ban on a regular basis, only to partly retract. This year, the song is allowed to be played on certain BBC stations in its original unexpurgated version, while younger-skewing music stations play a less offensive version. On 6 Music, it is being left up to individual DJs to choose.

It’s timely, then, to be bringing out a documentary about the man behind the song, a film called Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan, a film in which he admits he hates Fairytale of New York and wishes he’d never written it. The film, by director Julien Temple, fails to counter that without the song, the Pogues frontman would be around £20 million poorer.

Still, making a documentary about MacGowan doesn’t look easy. “No, it’s bloody difficult,” agrees Temple. “He wasn’t happy about it and the first thing he said to me is: ‘I’m not doing any fucking interviews’.”

But then you wouldn’t want MacGowan to be any other way. You want him inebriated, intoxicated, combative, looking like he’s about to topple over and off the sofa, or collapse down from the bar stool, or even flop out of his wheel chair.

“Frankly, he’s looked like that for years,” says Temple. “People have always wondered if Shane will make it to the next sentence without dying, or finish the next drink. And he always does, until he’s last man standing. Or sitting.”

There’s a scene in Temple’s new film Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan in which the film’s executive producer, Johnny Depp gets to interview Shane. The mere appearance of Depp might offend some viewers, given the recent failure of the star’s libel case and the very public revelations of his own copious drug and alcohol intake, relating to his now-tarnished reputation for domestic abuse. Depp and MacGowan clearly get warmed up, shall we say, as the chat goes on and Temple comes back to it a few times throughout the film even if it is mostly unintelligible and certainly not violent in any way, not that you can understand much of what they’re on about. I can’t believe there aren’t subtitles for most of whatever words MacGowan can dribble out between that massive gap where his front teeth used to be. Depp isn’t much more coherent.

The best bit is where the actor talks about his Pirates of the Caribbean films and Shane says he can’t be expected to watch to the end of those. And Depp admits neither can he. And they snort with laughter.

“Shane agreed to talk to Johnny as they’ve been mates for 30 years,” says Temple. “And they agreed to let me film it. They were talking for about eight hours, about Jerry Lee Lewis or Kris Kristofferson or God, they had long arguments about Harold and Maude and Oscar Wilde, and so there was only about four or five minutes of it that we could use in terms of what was relevant to Shane’s life story.

“Myself and the sound crew eventually stopped filming and had to go to bed and when we came back down the next morning to get the equipment and Shane and Johnny were still at it, still in exactly the same spots. We could have filmed 24 hours of them to be honest. Then we might have got six minutes we could use…”

Temple trails off. He doesn’t know if Depp’s involvement will harm the film or affect MacGowan’s reputation by association. Temple has a long history of making docs on difficult and recalcitrant musical subjects, from the Sex Pistols in The Great Rock and Roll Swindle and The Filth and The Fury, to Ray Davies of The Kinks, to Joe Strummer, Glastonbury, Ibiza and Oil City Confidential, about Canvey Island’s Doctor Feelgood. Why Shane MacGowan now? “He asked me,” is the simple reply. “Then bit my hand off anytime I tried to ask him any questions.”

So Temple had the idea of getting other people to talk to MacGowan, including Johnny Depp, Gerry Adams, Primal Scream singer Bobby Gillespie and MacGowan’s wife, the Irish writer Victoria Mary Clarke.

Gerry Adams might be the biggest surprise for many. The man who was banned by British TV, whose voice couldn’t be broadcast or face shown, now having a cosy fireside chat with MacGowan. “Shane is like a child when he’s looking up to Gerry Adams,” says Temple. “I’ve never seen him like that with anyone, showing a sort of reverence. They’re both steeped in Irish history and culture and I guess both have been outsiders. But that’s what time does and that’s partly what the film is about, that journey through time. All my films are about that, really.”

I’m reminded of the line in Chinatown, from John Huston’s Noah Cross: “Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.” I wonder if Shane is respectable or even likeable. Of course, MacGowan himself couldn’t give a tinker’s what I feel about him, but it does occur to me several times throughout the film, then, why I might be interested in watching him or hearing what he has to say. And yet I did watch, continually intrigued by the way Temple tells the tale. So what’s interesting about Shane MacGowan, what’s the story there?

“That was my struggle, too,” admits Temple. “I discovered early on that the real drama in him is about the dichotomy of him growing up in London as a first generation Irish kid, being teased, insulted, joked about, portrayed as thick, people doing the accent at you and suspecting you of being a terrorist. Remember that? It wasn’t so long ago.”

And Temple’s film flashes up IRA bombings, kids fighting in the north west London suburb of Kilburn and signs declaring: ‘No Black, No Dogs, No Irish’. London, lest we forget, could be a charming place in the early 1970s.

“But,” adds Temple, “there’s a romantic pull, too, because he was also one of the last kids to see that old, disappearing Ireland of the 18th century: no cars, no electricity, no running water. There were just horses and donkeys and he lived in it and remembers it. It was a lost world for him – five years later, when his sister was born, that was it – electricity brought the radio and TV and lights, and cars to rural Ireland but for Shane it was always the Tipperary of folklore. And that’s what churns inside of him.”

“I used to cry myself to sleep thinking of Ireland,” says MacGowan at one point in the film. He also recalls playing on the sand dunes and uncovering skulls and bones of the dead from the Great Hunger, and recalls the catechism and the beauty of the Catholic mass. He considered becoming a priest, he says, because drinking and smoking aren’t sins and he’s been doing that since he was five years old.

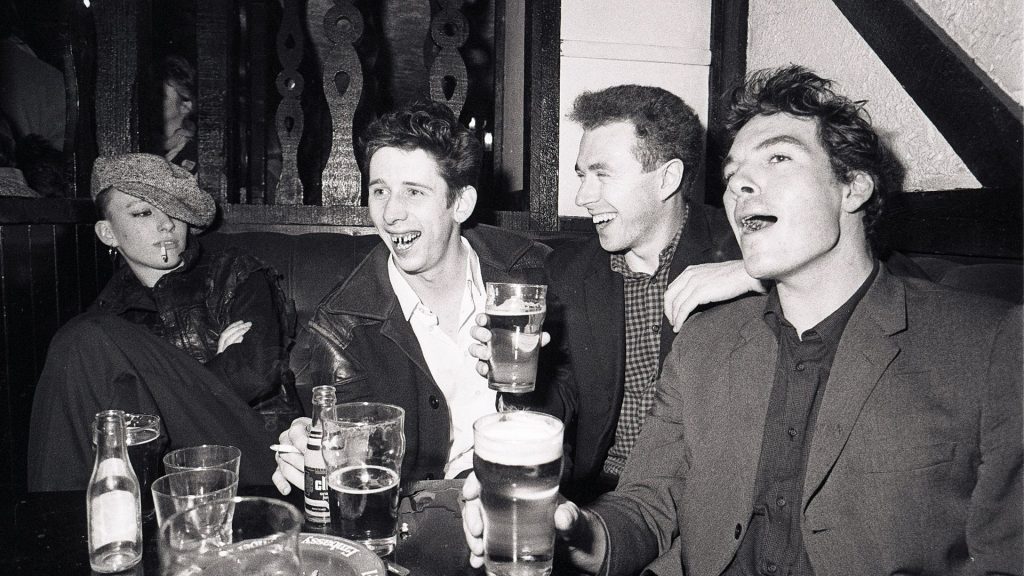

Temple illustrates all this with archive footage and photos, some of them ripped from the MacGowan family cottage wall, and taped back together for the purpose of the film. You can see the fading, the folding, the scratches and tears and the dog ears – its genuine stuff, almost ethnographic in the cloth caps, the gap-teeth, the simple farming folk in their field and the dry stone wall. It’s hard to believe, but there, almost like Zelig inserted into the action, is the young Shane, his face already that distinctive shape, tapering to a point at the chin.

There is also some documentary footage of the hard-scrabble rural life, culled from the few films made about that era, one of which was The Village, directed by legendary doc maker and educator Colin Young, who taught Temple at film school in London in the 1970s.

“My films are social documents and explorations, as much about me and you and the world we live in as they are about the musical figure who is ostensibly the subject,” says Temple. “So while Shane’s ability to roll with the punches, take the abuse and not walk off is a skill he’s learned and I think is worthy of showing, I see these films as looking at the world and the time the person comes from. Music is wonderful for this, because it’s not just about who wrote the song but about the audience who made it popular at a certain time, why that song, those lyrics, that performer came into being at a certain time.”

It’s a sterling defence of his subject, and indeed Crock of Gold can act as some kind of history lesson, including how Gerry Adams got respectable, or how a pogo-ing punk got involved in an episode of apparent cannibalism at a Clash gig at the ICA – a girl bit off his ear, it made the papers, and you can still see the teeth chomp in MacGowan’s lobe now – can then be hailed as the writer of the greatest Christmas song ever.

With Fairytale of New York, which played on the ever-popular notion of American Irishness (“the boys in the NYPD choir are singing Galway Bay” – there isn’t even a choir in the New York Police Department), in the news again this Christmas, Temple says he can understand why.

“It’s remarkable more than anything else,” he says. “I don’t think it’s a silly debate at all but a very relevant one – I don’t believe in censorship in the slightest but I wouldn’t want to be the BBC, the national broadcaster who have to play the song and where people might stumble across it.

“I put it in my film, of course, because it’s a defining moment in Shane’s career, but also the characters and lyrics are rather brilliant, the story it tells, but I also don’t believe people should be insulted for their sexuality, they don’t deserve that at all. But I’m a film maker asking people to pay money to watch a film about a man and a writer, I’m not the BBC putting it out there when there might be kids in the car asking their parents about it what it means.”

What you take from Crock of Gold is indeed the sweep of history. “I remember waiting for a bus and hearing a loud bang and there was a Jaguar saloon car 40ft in the air just a few yards down the street in Campden Hill Square behind me,” recalls Temple. That story of that constant tension of the IRA bombing campaigns is very much in the film, all the way through to the Birmingham Six being freed – as is punk, which Temple was part of and where MacGowan cut his teeth… and lost them.

There’s amazing footage of early Pistols gigs – which Temple has long been famous for capturing, of course – but there, right at the front is clearly the young MacGowan jumping around, gurning and grinning and shouting, again Zelig-like, just as he is in those Irish farming pictures.

“I knew him back in the punk moment,” recalls Temple. “He was a likely lad, and a firebrand figure of the era, certainly. I was the first person to interview him – that’s all in the film, him talking about getting out the old peroxide bottle, dying your hair to be a blonde punk and getting the street accent, the sniffing glue interview, I call it… I saw him as the photosynthesis of the energy of the stage and of the era. At the time, he was, what 15, 16, only just expelled from Westminster School, which he didn’t want people to know, of course.”

Temple stresses that he hasn’t been close to MacGowan or in any particular contact for many years. Temple was at the ICA gig where half of Shane’s ear went missing and had attended a few Pogues gigs. But essentially he was starting the film from anew.

The story of MacGowan’s family life does make compelling viewing, the story of growing up in the Barbican, where they were one of the first families living in that modernist construction and where, one night, a girl on a bad acid trip threatened to throw herself off the MacGowan family’s 16th floor balcony.

The drug taking is well reconstructed by Temple, using animations and archive of the Barbican being built and old Soho where sex shops and piles of rubbish mingle with late night addicts and beggars bent double. MacGowan wrote the classic Rainy Night in Soho, after all.

“My film has a time travel element to it,” says Temple. “I journey through time and learn as I go, seeing what turns up. That combination of the lyrics, the archive, the music is very rich so you end up with something transportive and poetic. And Shane wrote great songs about London and great songs about Ireland. He was definitely a product of both landscapes.”

Fog and bog, you might say. Looking at MacGowan in Crock of Gold you do wonder why anyone is attracted to him. He’s not charming, not particularly funny other than in his ability to drink or be rude or survive. Is that funny? Is that something to look up to?

“I think there’s something heroic, a hard-edged rugged poetry in it,” says Temple, citing MacGowan’s love of Irish writers from Brendan Behan and Flann O’Brien and James Clarence Mangan, whom, says Shane, “I loved because he was a drunk and a drug addict… I based my life on his.”

You don’t want the wrinkly old rock star interview with MacGowan, I guess, but you do want the impression of him built up through this mosaic. But he also restored a pride to Ireland and Irish culture, which is why he and Gerry Adams share such mutual respect, although the conversation is hardly scintillating nor particularly enlightening. “Punk is an Irish word, you know,” says Adams. “So is galore.” “Oh yeah, like Whisky Galore,” grins Shane, his head drooped to one side, a pose that will become familiar throughout the film, like an old teddy bear that’s had the stuffing knocked out its neck.

Shane is now 62 but, born on Christmas Day, he’ll probably make it to 63. There’s no doubt he looks older, maybe nearer 90, more like someone you’d find in a care home on the news than a punk poet whose performances, with his band, used to inspire huge crowds to jump and swirl with the spirit of the Ceilidh and the Fleadh.

I got the feeling people were talking to him like you would an elderly relative, as if losing your teeth made you a bit deaf.

“Yet I find there’s something noble in him,” says Temple. “I certainly didn’t realise what a mission it was for him to restore Irishness. He was on a crusade, as he calls it, it was to make Irish culture fresh, hip again, accessible, bring back respect for the culture and music, make it alive again… the music had been in a folky, museum-type setting and he made it vital again and the whole Oirish fantasy stuff, the ‘Darby O’Gill’ version (Temple is referring to the Disney film fantasy that starred Sean Connery in his first role) that Victorian England wrapped in tartan and whisky and caricature to cover up all the nasty stuff they were committing there… he wanted to blast all of that away.”

And you certainly don’t get the caricature version of Shane MacGowan in Crock of Gold. Instead, the rounded portrait emerges, from the punk and the public school boy rebel, to the drunk, the druggie, the poet and the romantic. As does the picture of London and Ireland changing.

The footage of Shane in his Y-fronts by the dirt-strewn canal in Kings Cross, well, I was down there at the weekend, strolling around what is now Coal Drops Yard, bursting with Christmas gear and expensive delis and chocolate shops and chorizo and brushed cotton.

If I hadn’t seen Temple’s footage and MacGowan and his cohorts horsing around in their video and deckchairs with their fags and tinnies on that same stretch of once-stagnant water a few days before, I wouldn’t have believed it was the same place. We live in cleaner, smarter, less inebriated times. Perhaps. Maybe there are just as many punks, addicts, drunks and tramps with their teeth falling out and they’ve just been cleared out of town, out of smart new London and the Regent Quarter of Kings Cross, where MacGowan used to flop and I used to rave a few years later but where the train now comes in from Paris and the farmer’s market charges £6 for a sourdough loaf.

Are we supposed to be romantic about the old days of drinking and taking drugs, of lying in rubble and freezing cold squats, of biting off ears and spitting and gobbing and racism? I don’t know. I find it hard to smile about it sometimes, when I see films like this that you could say romanticise. Mind you, do I like this new Kings Cross, with its concept stores and expensive cheeses, its coffees and eyewatering boutiques and Samsung gadget shop and its Alain Ducasse chocolates? Shane MacGowan would kick the windows in, I reckon. If he could stand up long enough.

“Change is what it’s about,” says Temple. “That canal is a good metaphor, how slowly it flows, and what’s at the bottom and how its uses change. But some things alter beyond all recognition, like Kings Cross. Some things never quite get there.”

Is that what the Crock of Gold is then, I ask, referring back to the title of this rollickingly entertaining film about a very difficult to define, hard to love, character. “Oh that’s an existential question,” says Temple. “It’s different things for Shane and for me, for the poet and the film maker. For him, he says he’s been searching for it all his life. In Celtic myth, of course, it’s the pot of gold coins, the crock, and you could say Shane is an old crock and that he has gold inside that ravaged exterior.

“For me, it’s philosophical and spiritual satisfaction of some kind, something we’re searching for, a sense of peace. It’s hard to achieve – maybe the next film is always the crock of gold, and you don’t know how to get there, and it’s always receding as you approach it. That must be it.”

Crock of Gold is in cinemas now, and also available on DVD and digital. For more information, visit crockofgold.film

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37