A new film about three giants of football, who not only revolutionised their clubs, but galvanised communities, defined cities and shaped modern Britain.

Footballing dynasties feel like a thing of the past.

Certainly these days, when football itself plays out in empty stadia around most of Europe, vast bowls echoing to the sound of bellowing coaches, exaggerated howls of pain after innocuous-looking tackles, and the occasional clack of ball on goal post.

How very different from the days when 140,000 would attend games in Glasgow, regularly breaking the world attendance records, or the heyday of the swirling, swaying tide on the Kop at Anfield and the buzz of the ‘Babes’ lighting up Old Trafford.

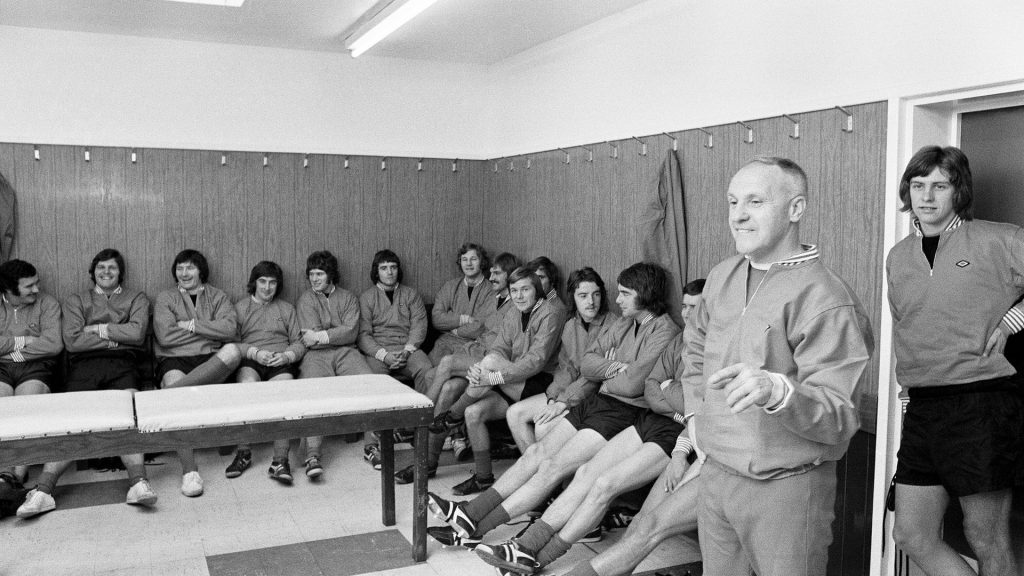

These are the images and scenes created by three Scottish men: Matt Busby, Bill Shankly and Jock Stein (at Manchester United, Liverpool and Celtic respectively). And these are the scenes captured in a new documentary about them, The Three Kings, which traces the founding of their footballing dynasties, taking their clubs to heights of national and European fame to make histories and brands that still have impact today.

The three Scots were born within a 30-mile radius of each other, hewn from the Lanarkshire soil. Quite literally, as all three were also miners at the age of 16, before resurfacing and opting for careers in football. There’s a wonderful clip in the film of Welsh actor Richard Burton extolling the respect in which miners were held in working class hierarchy: “They were the lords of the coalface, and you could spot the arrogant strut of these gods of the underground.”

Directed by Welsh actor, broadcaster and film maker Jonny Owen, The Three Kings is as much a social history as it is about football, a portrait of Britain emerging from the rubble of the Second World War – Old Trafford, for example, was bombed and rebuilt – through the austerity of the 1950s and into the swinging 60s of The Beatles, colour footage and long-haired Georgie Best. It’s an extraordinary journey packed with so much incident which has shaped British popular culture over the ensuing years.

The film also comes from the stable of James Gay-Rees, the producer behind the documentaries Senna, Amy (Winehouse) and Maradona, so the cinematic pedigree is assured and the film manages to cram in so much history alongside some great goals that could have been scored yesterday. Or not, actually, because there are huge crowds cheering each time the net ripples. Oh, how I’m missing my footy.

“That’s the point now, isn’t it?” agrees Jonny Owen. “It is of course a different time and the past is a foreign country and they do things differently there, we know all of that, but I just suspected the contribution individuals can make to history and to entire cities can risk being forgotten, so that was the impulse behind wanting to make this film and I wanted to bring the story to a new audience who might have forgotten or never knew, if all they remember is the founding of the Premier League.”

Owen has previous in this regard, starting with his 2015 film I Believe in Miracles which told how Brian Clough led unheralded Nottingham Forest to two consecutive European Cup triumphs, in 1979 and 1980. It also showed how Clough hauled an entire city out of obscurity and put it on the European map, one man changing the history and perception of a people and buildings.

“It’s about how a man can imprint and impact,” says Owen. “There’s something in the connection between a football crowd and a certain individual that exerts a phenomenal power that can change a whole environment. Maradona had it in Napoli, Clough in Nottingham, and the more I researched, it was clear that these three Scottish men had altered the course of history in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow.”

Despite the familiarity of much of the material, Owen deserves praise for finding a new path through the archive. I must admit, I’m a huge football fan – a former football reporter, don’t you know – and I’d never seen the Munich air crash, in February 1958, so emotionally covered.

I think it’s because it was from the point of view of Busby as this paternal figure, bringing through a bunch of youngsters in Manchester, having promised their parents he would look after their boys. And then, having fashioned this thrilling team, by all accounts the finest anyone had ever seen in Britain in terms of flair and pace and youthful swagger, to count their deaths and see them lying in the wreckage on the Munich runway.

More shocking still is the footage I’d never seen of Busby himself in his hospital bed, zipped up in a protective plastic bubble, apparently not wishing to ever come back to consciousness.

Later in the film comes the tragedy of Jock Stein’s collapse, live on television, after a Scotland vs Wales World Cup qualifier. And of course, there’s Shankly himself uttering his famous quote, when asked about football being a matter of life and death, that it’s “more important than that”.

There’s something ghostly about all this archive, all this history that haunts us still. “I wanted to show that the past makes us what we are now,” says Owen. “And that some things were a lot worse back then – but some things were also a hell of a lot better.” Supplying the voice overs are the revered football writers Richard Williams, Patrick Barclay and the legendary Scottish football presenter Archie Macpherson, who also wrote the definitive biography on Jock Stein.

Their comments and observations provide a strong framework and reference throughout, connecting the past to the present, wise voices who have followed it all from a distance and can put every decade, every moment in some kind of context. It stops anyone getting carried away on a tide of roseate memories. The archive, too, features the voices of great commentators and reporters of the past, Brian Moore and Barry Davies, who were never short of a lyrical moment to describe the tumult and grandeur of football’s big days out, the Wembley tunnels and the laps of honour.

What, for instance, can modern football learn, then, from the iron will and iron rule of these men as they created their teams, forged their football grounds and moulded entire communities in their own characters? “I think there was a sense of football as socialism,” says Owen, himself the son and grandson of miners, from Merthyr Tydfil, with its own proud history of cup exploits. “You got the feeling of a football team such as Celtic or Liverpool on a Saturday afternoon or on those glorious European nights as they started to build up, of the terraces as a ‘big society’. You can hear it in the quote we’ve got of Shankly saying he gave everything for the job because it was ‘for the people’.”

The Three Kings clangs to the sound of industry, to coal and ship building, to swathes of workers clocking off at the docks on a Friday to them pouring into Celtic Park or Anfield on a Saturday. “Look, I can get too romantic about it all, too sentimental,” says Owen, “but there was definitely something unique happening at these three cities.

The football clubs are worth billions to the economies of those cities, and their names are known around the world. There’s an estimate that two billion people globally support one of these three clubs and there’s no doubt it was down to the energy and determination of these three men who wanted to build something. Their teams end up personifying the cities.”

As for the football itself, that builds to the finals of the European Cup in 1967 and 1968, when suddenly the footage bursts into colour, as if victory itself brought Britain out of the dark. I’d certainly never seen film of Celtic’s final against Internazionale in Lisbon in 1967, when this relatively unknown team in the distinctive green hoops shocked Europe and became the first non-Latin team to carry off the trophy made famous by big names like Real Madrid.

And Manchester United following them the next year, with their win over Benfica, in extra time at Wembley, with George Best having his finest hour. Almost as important, though, is a save goalkeeper Alex Stepney makes in the last minute of normal time, standing up to the great Eusebio as he races through, one on one, only the keeper to beat to assure glory. It’s a breathtaking moment in the film.

“I love that footage,” says Owen. “It just looks of its time, that stock from the mid-60s, you just can’t recreate it. Most people cite the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, and those gold Brazil shirts, as the watershed moment for colour coverage of football. But that year, 1967 Celtic, there was a camera crew following them around, filming, so that’s why there is quite a bit of colour film of them in the archives. And it happened to be the year when they won everything, domestically and then in Europe, and it is probably still the most incredible footballing achievement by any team, for me, ever.

“But, would you believe this, at half time, in the final of the European Cup, that was when the crew ran out of the colour film. That was it. No more stock and you’re there in the Estadio Nacional in Lisbon, and the team you’ve followed all this way, and you’ve no more film? Can you imagine the panic whoever produced that film must have had? Or the b****cking the cameraman must have given his runner? Anyway, so that’s why I’ve had to go back to black and white for the climax of it.”

Perhaps even more extraordinary than what Stein’s Celtic side, who came to be known as the Lisbon Lions, achieved that year – five trophies in all – is the fact that all but one in the 15-man squad were born within 10 miles of Celtic Park. (The outsider was Bobby Lennox who came from Saltcoats, fully 30 miles away.) There is just something in the water sometimes, and it takes the right man to bring it all together, recognise it and build from the foundations up.

“My theory is that the mines made them, yes,” admits Owen. “There was something about the way miners were led, by the union men, who were brilliant at arguing their point and getting large numbers of people on their side, to gather, to act as one, to inspire them. That’s perfect conditions for becoming a football manager and that was the prevailing atmosphere among mining communities, that there were always such inspirational figures around who would lead and know what to do, in whom you could put your trust that they would look out for you. That was the spirits these three had in their clubs as they built them, practically from scratch.”

That’s what Busby, Stein and Shankly were allowed to do. It’s hard to imagine another similar dynasty germinating anywhere in modern European football now. You get a few shots of Alex Ferguson, who was Stein’s assistant as Scotland manager, and who obviously went on to create his own dynasty at United, one comparable to Busby’s. Yet Owen cites Arsene Wenger, who in 22 years at Arsenal changed the face of the game in Britain.

He’s right. I’m writing this positioned in between the old Highbury Stadium in north London, now turned into luxury flats, and the gleaming, modern, empty Emirates Stadium, which doesn’t yet have half the atmosphere, the stories, the history, the soul of the old place, not for me – the place where I grew up and shouted and yelled and left my spirit and breath in the air of the old North Bank, carried by impetuous youth and waves of other fans. Islington itself morphed into a cosmopolitan hub, full of modern European restaurants and street cafes, French clothing boutiques.

“Wenger did change a whole area, didn’t he?” suggests Owen. “He changed the way football was played, what footballers ate, the sort of players English clubs should buy and look for. And after him, comes the influx of foreign managers such as Mourinho. But I can’t see anyone lasting 22 years again. I’m not sure that local connection is there anymore among the big teams.”

Fascinating, too, to remember how we used to support the British teams in Europe. I jumped for joy when Eric Black put a header past Real Madrid to help win the Cup Winners’ Cup for Aberdeen in Gothenburg 1983. We all wanted Forest to win in Malmo, and how about Aston Villa in 1981 against the mighty Bayern Munich in Rotterdam? We all wanted them to win, and they did.

The Liverpool teams who’d had such European success before them, and Celtic and United before them, they were in a sense, national teams. Not now. I can’t imagine wanting Chelsea to win a European final, nor Spurs, nor Manchester United. I don’t even think it’s heretical anymore to want a foreign side to win – I admit I did want Anderlecht of Belgium to beat Spurs in the 1984 UEFA Cup Final, but of course, that’s allowed.

My own kids have Barcelona, Juventus, PSG and Atlético tops, to go with various iterations of Arsenal over the years. All of these are items, artefacts I could never dream of as a boy, and even as we kicked the ball around on the pitches in the shadow of the Emirates, the children around us on the recent half-term break sported Brazilian teams, Chelsea tops, a Colombian national strip, a Portugal shirt and the names of Messi, Ronaldo, Neymar to the fore. Some kid had a Bayern goalkeeping strip, the whole thing, including gloves, with Neuer on the back.

“The Busby Babes were certainly the team for the whole nation,” says Owen. “My dad and grandfather followed them avidly on their European nights. Everyone in Wales cheered for Aberdeen that night against Madrid. And we always had great respect for Jock Stein in Wales, having known he was a miner, so he was one of us, you know? But those were the connections, they were local and national.

When United lined up at Wembley in ’68, I’m sure the whole of Great Britain wanted them to win. I don’t think anyone ever wanted the foreign teams, did they? It would have been frowned upon, to say the least.”

We wonder when it changed, all of that. The Champions’ League will have had much to do with it, meaning that several Premier League teams competed in the same tournament, where previously there was only one team from each country – so they sort of represented your league.

Perhaps Manchester United winning in 1999, with Solskjaer scoring with almost the last kick of the game, was the last time a whole nation cheered a club side? Even I grudgingly jumped out of my seat at that moment, and that United side were my Arsenal’s fiercest rivals.

So yes, maybe that was the last time. Certainly, by the time Russian-backed Chelsea were in European finals, surely nobody outside Stamford Bridge – and the seedier parts of Surrey – was cheering for them?

“I think the Busby Babes of the late ’50s were the first team who fans might have tried to emulate in terms of style,” says Owen. “They had the Brylcreemed hair, they were young, that deep white V-neck shirt was pretty revealing for the post-war sensibility. They set hearts racing.”

Nobody had replica kits or anything, but there were cigarette cards and the beginnings of a pop culture that saw posters in comic books and annuals. By the time of the Fab Three, of Best, Charlton and Law in the mid-1960s, there was a definitely a sense of footballers becoming style icons, even though the merchandise culture was light years away from where it is now. You were lucky with a wooden rattle and an itchy scarf that was vaguely in the same colour wheel of your team’s strip.

Football is, clearly, a handy canvas for nostalgia, for misty-eyed sentimentality – jumpers for goalposts and all of that. And yet, as The Three Kings reminds you, in the moment of it, there’s no room for sentiment, and certainly Shankly, Busby and Stein never traded in it.

Their own empires come to sad ends, all three. Busby not able to relinquish power, always hanging round like a reproachful ghost over the managers that follow.

Shankly, they say, eventually died of a broken heart, having decided to retire, all of a sudden. There’s some great newsreel of a BBC reporter breaking the news of Shankly’s decision to some Liverpool fans in Trafalgar Square for their reaction, and they simply don’t believe him. Even as Shankly’s dynasty – founded in the famous Boot Room – carried on with Bob Paisley, Joe Fagan and on to Kenny Dalglish, the man himself could never come to terms with not being in charge any more.

And Stein, well, he’s certainly one of only two people I can recall who have died live on British television while I was watching, Stein and the comedian Tommy Cooper. Stein, who’d left Celtic and been given the task of taking charge of the Scottish national football team, was in the cramped, dug out as Scotland took on Wales at Ninian Park, Cardiff, and scored a late penalty to qualify for the 1986 World Cup in Mexico. Stein collapsed on the touchline and was carried down the tunnel, towards a medical treatment room where he died shortly afterwards. I remember watching it.

“I was there in the ground that night,” Owen says, besting me easily. “Obviously, as a Wales fan, we were gutted about not getting the result we needed, yet again falling at the last hurdle of qualification, but I can tell you every one of us was far more upset about Jock Stein. He was one of us, one of the people.”

And that’s it really. These men who founded dynasties in their own fashion, after their own moral and social codes, were normal men. Not wealthy, not untouchable executives. We see Shankly’s house, a modest semi-detached. They didn’t drink, hardly. The only time Shankly and Stein had a tipple was whenever they met up with Busby, who, according to Owen, liked a sweet sherry now and again. They just got on with building their clubs up into monumental structures, ones with remarkable foundations that, even in their absence, have not crumbled – although there was, amazingly, that lasting trauma of Busby’s departure that led to United’s shock relegation in 1974 from the old First Division, the dagger blow supplied by former darling Denis Law, back-heeling it in for bitter rivals Manchester City.

The Three Kings is a tale of the past and of long-departed old men, who came from the tough ground of Scotland to create lasting greatness, whose exploits were admired around the world. In an age of billions, of breakaway leagues, of Big Six, of American or Russian ownership, of TV deals and silent stadia, the voices of Busby, Shankly and Stein are no longer delivering their granite wisdom.

My word, would they have had something to say about pay cuts and pay per view and not having fans around to inspire and entertain and make dream. But in this fine film, you can hear them again, and you remember that, whenever you watch football now, at home or in Europe, their heartbeats, however faint, can still be heard. You just have to listen.

The Three Kings is released on DVD on November 16 and is available for streaming on Amazon, Virgin, iTunes, Sky and Rakuten

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37