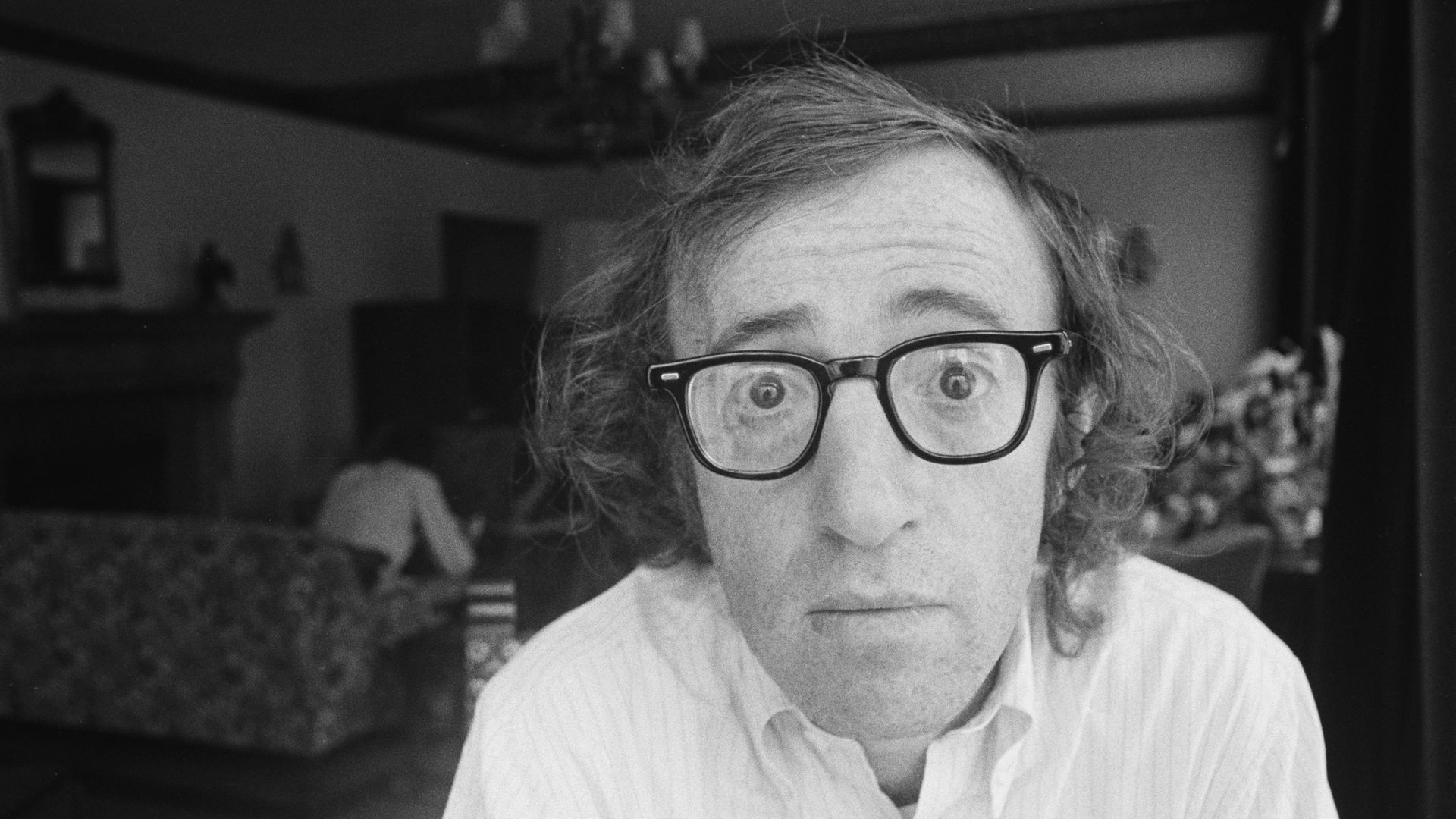

A new four-part HBO documentary assembles a compelling and gruesome case against Woody Allen. JASON SOLOMONS, who has written a book on the director and a long-time fan, describes how watching the series has changed his attitude towards his hero forever.

Starting in the pit of my stomach and rising to the bottom of my throat, the nausea came like waves. I found myself sweating, panicking, like a claustrophobic. The walls were closing in.

This is how I felt watching Allen V Farrow, the four-part HBO-produced documentary that has been gripping America over the last few Sunday nights and is sure to do the same in the UK when it airs on Sky Documentaries on March 15. The way the evidence is presented, the lush music score, the tearful confessions and recollections, the legal and expert testimony, the shockingly explicit accusations – I was gagging on it all, as “naw-tious” as the famously neurotic comedian at the centre of it all is so fond of saying, usually for laughs.

Perhaps that’s what the filmmakers, co-directors Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering want us to feel. The way they build their case is brutal, cold-eyed and thoroughly convincing for as long as the narrative holds you in its vice. It is also devastating for Woody Allen fans.

My response, I should confess, is very personal, although I think most people’s will be, too.

In 2015 I wrote a decent-selling book, Woody Allen: Film by Film. I interviewed Allen for it, getting to sit down with him in a Cannes hotel for 50 minutes after the premiere at that festival of his latest film, Irrational Man, starring Emma Stone and Joaquin Phoenix.

The book examines 50 years of his films, from 1965’s What’s New Pussycat to 2015’s Irrational Man. Of course, it looks at how he has put himself in these pictures, and how his various on-screen characters might be a version of his true self. Or not. The book is aware of the scandals that marked his life in the early 1990s, when he began an affair with Soon-Yi Previn, the teenage, adopted daughter of his girlfriend of 12 years, Mia Farrow.

He was also accused, by Mia, of molesting seven-year-old Dylan, whom he had, by August 1992 when the alleged offence took place, then adopted and become legal father to.

I didn’t go into those events too forensically. I concentrated on the films of that time, of which 1992’s Husbands and Wives is the most extraordinary, completed while the shock reveal of his affair with Soon-Yi (discovered when Farrow found a pile of ‘pornographic’ Polaroid photos of her college girl daughter in Allen’s apartment) still reverberated around Mia’s soul. That film contains the line: “It’s over, and we both know it.”

Only it wasn’t over for Allen. He went on quite merrily making films, at the legendary and lauded rate of one a year, from Manhattan Murder Mystery to Bullets over Broadway into Sweet and Lowdown in the 1990s, to Melinda and Melinda, Match Point and Vicky Cristina Barcelona in the 2000s and Midnight in Paris and Blue Jasmine in the 2010s.

I went on watching these movies, even loving some of them, interviewing their stars from Radha Mitchell and Chloe Sevigny, to Emily Mortimer and Penelope Cruz, Lea Seydoux and Cate Blanchett, all with their gushing appreciations of the parts Allen had written them and how they’d taken their berth in the gallery of ‘Woody Women’ that already included Diane Keaton, Farrow herself, but also Dianne Wiest, Barbara Hershey and Gena Rowlands. Only Marion Cotillard said she’d had a bad time, but not due to any abuse – more that Allen ignored her much of the time when she wasn’t on camera.

When the book went into a second edition, I was thrilled and updated it with the new movies Allen had made in the interim (including Cafe Society and Wonder Wheel) and I got another interview, again at Cannes. However, on that very day in May 2016, the Croisette was in crisis as the Hollywood Reporter published an accusatory column penned by Dylan Farrow, admonishing the festival for celebrating the man who she maintained abused her as a seven-year-old.

It’s a moment that features in the final part of the new documentary, as if to illustrate how the world of Allen still went about its business. There was a celebratory lunch for Allen that afternoon that went ahead – although the HR was banned. I still got my interview, a very pleasant, stimulating hour in which he gave me his full attention and never shirked a question, talking about jazz, marriage, the women he’s worked with, the philosophies he’s espoused and examined in his work.

At the end, off the record, I explained to him I was concerned that maybe I had dedicated much of my artistic and professional life to his films, and that, you know, what with all these allegations resurfacing, could he please promise me I hadn’t backed the wrong horse?

“You got nothing to worry about, kid,” he said, putting his soft hand on my shoulder and looking me right in the eye.

*****

Despite that, by the time the second edition came out, amid the furore of Harvey Weinstein’s downfall sparked by the dogged investigations of Ronan Farrow (Allen and Mia’s only biological child), the reckoning of the #MeToo movement and the increasing support – from public and celebrities – for the now adult and emboldened Dylan (#ibelievedylan), I felt that my book celebrating Allen’s films was derelict in its duty. I requested that the publisher pulp it, only it was all piled up in a warehouse already, waiting to ship out.

It still sold pretty well. and pretty soon I was at a packed Royal Albert Hall watching Allen and his clarinet honk through an evening with his New Orleans Jazz Band.

I spoke to Allen again, twice, last summer on the phone, while he was holed up against the coronavirus in his Manhattan apartment, as his autobiography A Propos of Nothing came out and his much-delayed, practically cancelled movie A Rainy Day in New York was finally released in the UK. It was getting harder to even sell a piece about Allen. I sensed people’s wariness around him. Celebrities who’d worked with him were repeatedly and publicly wishing they hadn’t – Colin Firth, Kate Winslet, Mira Sorvino, Timothee Chalamet.

I asked him about the allegations again, straight out, and about how he’d become, in the sudden parlance of that time, “cancelled” and “toxic”. He again, denied any accusations, saying: “All I can do is work, ignore the nonsense, and people who are interested enough can investigate the story in my book or any thinking person would come to the conclusion that the investigators came to at the time, that this was non-event and pre-fabricated and just didn’t happen and every independent investigation and there were a number of them, would come to that exact conclusion and I don’t think most people have the time or interest to investigate it.”

But now, in Allen v Farrow, people have been bothered and interested, and they have investigated again and lifted the lid on boxes long shut. There are allegations of cover-ups, destroyed interview evidence, of powerful elites wanting the story to go away, suggestions that Allen was simply too vital to New York – perhaps because his films there brought millions to the city coffers? – to be allowed to fall.

*****

Queasy as I have been about this gradual but ineluctable turning of the tide against Allen, I have always defended my right to enjoy his films and I’ve steadfastly kept Annie Hall as my Number One movie – it’s a question you get asked a lot as a film critic, so much so that changing it becomes practically an existential issue, especially when you’ve done plenty of public events around it, including headlining a season called “The Film That Changed My Life” with it at London’s Barbican.

Look, the new documentary doesn’t provide definitive evidence that Woody Allen abused his daughter in an attic crawlspace in Connecticut on August 4, 1992. It doesn’t. And the defensive narrative, spearheaded by Allen fans such as Bob Weide, the Curb Your Enthusiasm director, who also made the definitive American Masters documentary on Allen, now focuses on the existence (or non-existence) and size of an electric train set Dylan says she fixated on during the abuse.

The details are horrid to hear, horrific to imagine, almost impossible to believe. It may have only been the once, and there’s no suggestion of serial abuse or abuse anywhere else, but that’s no defence, is it? Once is too much, although that, now, is probably impossible to prove, too.

But the prevailing culture has changed and this is what the documentary quite persuasively constructs: how Allen has been able to control the narrative and limit damages, even staying married to Soon-Yi (the Farrow family pronounce it ‘Soo-knee’) whom he married aged 62, when she was 27.

There are suggestions resurfacing in the doc, that their affair began when the girl was still in high school, according to a maid’s report about finding condoms and semen stains on the sheets in his apartment. There’s footage of him leading her out to dinner, or through the streets and it looks like an old guy kidnapping a little girl. It’s all heavily loaded imagery, but it builds up.

*****

So these smears pile up until they become a thick impasto over the Allen name and brand. He, without seeing the documentary, has labelled it “a hatchet job riddled with falsehoods”. He continues in a statement: “These allegations are categorically false. Multiple agencies investigated them at the time and found that, whatever Dylan Farrow may have been led to believe, absolutely no abuse had ever taken place… While this shoddy hit piece may gain attention, it does not change the facts.”

Viewers will find themselves trying to read meaning, facts, into still photographs and home video footage of Allen cuddling Dylan, which is of course cheap and dangerous documentary film making. Witness statements from Mia’s family friends and various nannies and tutors who used to throng around her house also supply a decent wattage of creepiness.

“I saw his face in her lap,” and “Dylan used to hide from him”, “I was in his clutches,” and “I saw him getting out of bed with Dylan just in his underwear,” or “I saw him teaching her how to suck his thumb…”. And then family friend and Mia’s building mate in The Langham in New York, Carly Simon, pops up to say “He spent a lot of time grooming Soon-Yi.”

That word pops us, carefully, but frequently. Female film critics (such as Alissa Wilkinson, Claire Dederer and Miriam Bale) appear, lecturing us old white males on how Allen’s screen persona has “in a sense been grooming us,” that through his stories of inappropriately aged men having on-screen relationships with younger women, he “has been acclimating us to his predation”.

I can and have retorted to this. He’s made 50-odd movies and, yes, in six you could say there are some relationships between Allen’s character and a younger woman, and they are mostly set against other more age-balanced relationships in the same movies. So yes, the impulse to be younger, date younger is within the man’s psyche and within the compass of his imagination, as much as Martin Scorsese knows where bodies are buried or George Lucas can fly a Millennium Falcon, or Bela Lugosi bites necks.

And then we see, for the first time, the video of little Dylan, at her mummy’s prompting, showing where Daddy touched her.

As I said, it piles up and my nausea built with it, the creeping, dawning sense that I’ve been backing the wrong horse all along.

However, just as Allen, according to Mia’s children such as Fletcher Previn and Ronan Farrow hired private investigators and used his “limitless resources” to go through their trash and follow them and tape their phone calls, these docs could be seen as the Farrows getting their revenge, using new digital technology and film techniques to sift the trash of Allen’s life, to look at the off cuts, the crossings out (including the Princeton Papers archive containing all his old notes and abandoned ideas), the off-camera moments.

A keen teenage magician, Allen has often put magic in his films and talked of “sleight of hand”, making people look the other way. Allen v Farrow redresses that, and makes a new audience stare very hard in one direction. As the writer Lili Loofbourow says: “When you’re forced to look, to see and to know something, it’s so dispiriting, so hopeless and so uncomfortable that it’s sometimes easier to opt out.”

Perhaps what I found most disturbing were the taped conversations between Mia and Woody – both were taping each other’s calls, unbeknownst to the other, most likely on the instruction of lawyers, but we now hear those conversations with transcribed subtitles.

Mia sounds desperate, lost, pained and it’s distinctively the voice we’ve heard several times in her movies, as Cecilia or as Alice, or even in Rosemary’s Baby; Allen, however, adopts a far more sinister tone than I’ve ever heard, during a lifetime of listening to his stand-up records, his movies, and transcribing his voice in interviews in my headphones.

“No matter what I say, when I talk, it just comes out funny,” he told me in one interview, a quote we even put on the book jacket. But here he’s not funny at all – he’s threatening, heartless, cold, like one of the characters in the films noirs he often spoofed, maybe like the gangster, Jack, played by Jerry Orbach in Crimes and Misdemeanours, who helps his brother Judah, played so brilliantly by Martin Landau, by bumping off his ready-to-squeal mistress (Anjelica Houston) and who convinces Judah that if you can square it with your own conscience, you can get away with anything.

*****

I would hope I’m strong enough to make up my own mind. This film is almost unethically one-sided, ignoring, for example, Moses Farrow’s quite harrowing accusations about life for all the kids with Mia which he published on his blog. Even that hoary old trope about separating the art from the man is brushed over here, merely mentioned as a montage of Bill Cosby, Roman Polanski and Harvey Weinstein floats across the screen – all of whom were found guilty, where Allen wasn’t and, say his defenders, he shouldn’t be lumped in with these miscreants.

As if to emphasise the film makers’ bluntness, there’s a close up of Kevin Spacey at the 2014 Golden Globes, clapping as Diane Keaton takes the stage to eulogise for Allen’s Cecil B De Mille award. Allen’s one of The Usual Suspects now, runs that subtext, the devil who’s trick has been to convince you he doesn’t exist.

Back last summer, Allen admitted to me he may have made his final movie. Rifkin’s Festival debuted at the San Sebastian film festival – where the movie is set – in September even amid the coronavirus epidemic. But its roll-out has been delayed. Perhaps nobody wants to see it. There are those who now won’t watch another Woody Allen movie and, although he has written a script set in Paris and was, he says, all ready to shoot it there last summer, he may not get that off the ground. He can say that’s down to social distancing, but it’s more likely another form of distancing as this documentary rolls out around the world.

So, is Woody Allen finished? I can only think that is, ultimately, the chief aim of this documentary. It rather weakens its own case in the final stages, concentrating on Dylan herself, showing moody shots of her all contemplative by a lake and talking solely about herself and her feelings as an “incest survivor”, rather than, say, mentioning she’s doing this to let other victims know they’re not alone, or to share the patterns of abuse with other so that they might recognise it and avoid it.

No such public-facing generosity of spirit comes across – it simply feels like bitter revenge to bring down the image of her “tormentor” and crush any celebration of him.

Allen is 85 now, still holed up in his apartment, with Soon-Yi and their two adopted daughters Manzie and Bechet. He’s written that Paris script, which was supposed to mark the official 50th movie of his career, according to his own count. Cannes was, I hear, standing by to welcome him with a landmark screening. A “WoodyFest” feels a long way off now. The French will protest anything and you can imagine quite the march along the Croisette against that.

He told me he’s also written a play. Maybe someone will put up the money for that. Maybe a venue will open and people will even turn up to watch it. I doubt New Yorkers will, now. He was so bound up with the fabric and identity of that city, as neurotic, Jewish, romantic, smart, lovelorn, restless, punchy, funny, that he kind of represented all of them. In a way all fans of his work have felt like that, inspired by him, connected to him, personally embodied at various times by his characters’ thoughts and jokes and travails.

But the child abuse, not so much. The powerful crushing of opponents through cover-up and media trials and PR, perhaps not so much. He’s not their New York any more. And betrayed New Yorkers do not forgive, especially when it lets the rest of America vent their envy on them, and even their anti-Semitism, of which there is always at least a whiff when a prominent Jewish figure gets taken down.

I still love Allen films, apart from The Curse of the Jade Scorpion and Anything Else and Scoop. I think they will survive us all and I’ll watch many of them again (Sleeper, Love and Death, Annie Hall, the opening sequence of Manhattan, Hannah and her Sisters, Radio Days, Purple Rose of Cairo, Crimes and Misdemeanours – these are all brilliant) and I’ll laugh and I’ll feel their angst and wit and share their human condition.

But I can’t look on him as a hero anymore.

Allen v Farrow is a thoroughly nasty business and I wish I’d never seen it. Despite what that kind and generous, warm and charming Woody Allen once told me in confidence, I got plenty to worry about now.

Allen v Farrow is available to watch on Sky Documentaries from March 15

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37