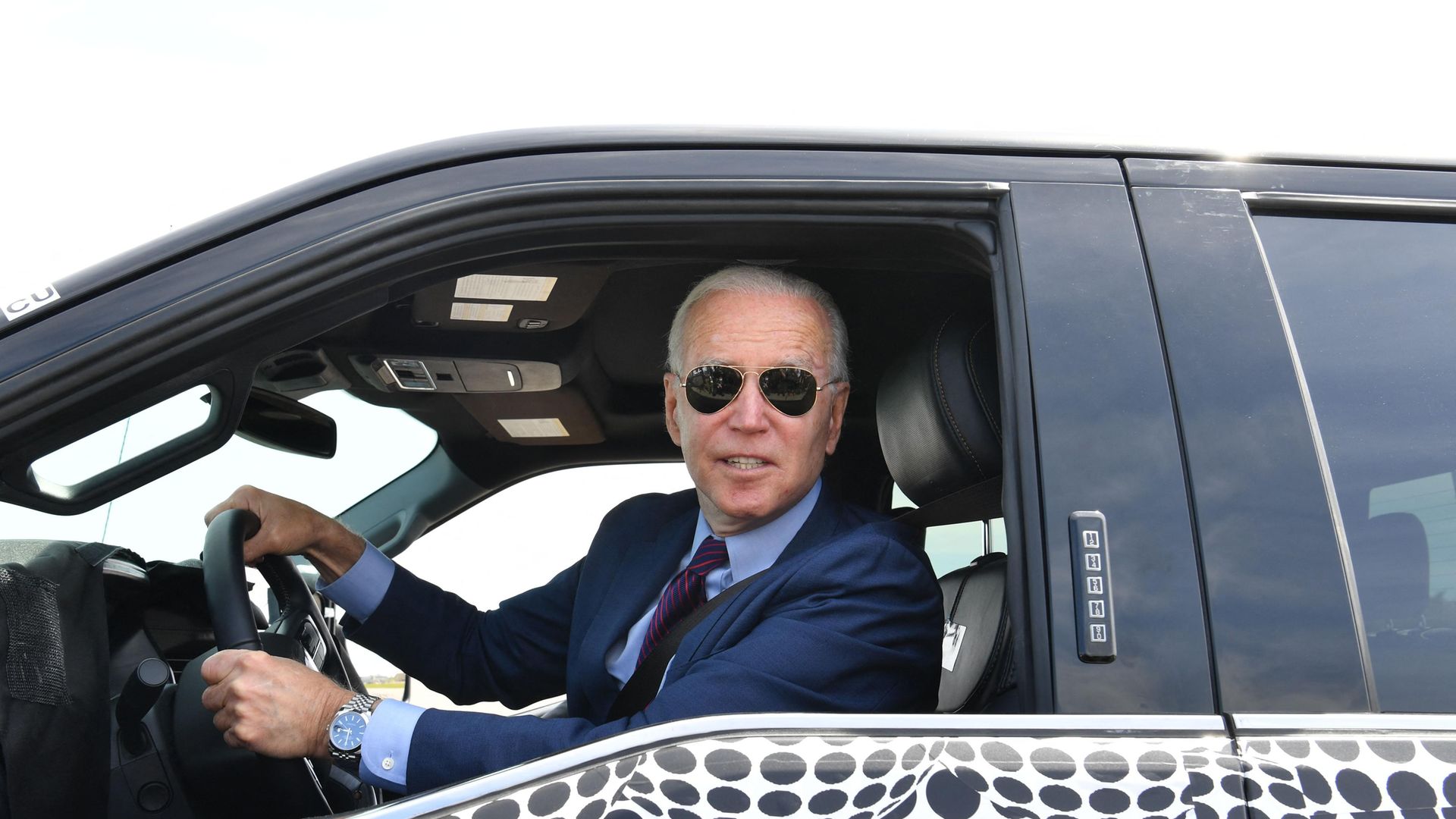

The US president was expected by many, including his supporters, to be an uninspiring, unimaginative and ineffective leader. He is confounding those expectations in spectacular style

When Joe Biden seemed to just limp over the line in the race for the White House last November, the considered opinion seemed to be that the nature of his victory – and the timid campaign which had preceded it – would usher in a cautious, circumspect and rather feeble presidency.

Here was a laid-back, ageing leader who would be content merely to steady the American ship after the storms of the Trump presidency, and not much more. Sleepy Joe, after all, seemed to be one of his predecessor’s better barbs.

Now, as his presidency enters its sixth month, Biden has rather shattered those (albeit absurdly low) expectations, launching a series of bold, and often very left wing, initiatives on a bewildering array of policy areas, throwing down the gauntlet to vested interests from Big Pharma and Silicon Valley to the US military.

The scale and ambition of his radicalism stands in stark contrast not only to the sclerotic Trump era, but also the eight years of the Obama presidency, which promised so much, but delivered far less.

One of the most significant of Biden’s early decisions has been to accelerate with withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan – something Trump had also promised to do, only to be confounded by his generals.

After two decades of criticism from the left of the USA’s post-9/11 “forever war”, Biden overruled the Pentagon to insist all US soldiers would be out of Afghanistan by September 2021. Reporting this week suggests the process is going even faster than expected, with troops currently set to be out of the country by July.

The withdrawal is not universally popular nor without risk – it leaves the future of Afghanistan in a deeply uncertain place, though critics would note continuing US presence does the same, but it represents the end to a far longer deployment than most US citizens ever imagined, and what had become seen as a pointless, deadly and costly intervention.

Of less symbolic significance, but far more practical use to most Americans, has been Biden’s epic, expansive coronavirus bailout package. Rather than some stodgy compromise package with Republicans, Biden passed a $1.9 trillion deal – hailed by his left wing primary opponent Bernie Sanders as the “most significant piece of legislation to benefit working people in the modern history of this country”.

The plan included additional $1,400 stimulus cheques to most households, and an extra $300 on payments to unemployed families. But it also introduced a child tax credit for the first time in the US, and created new tax breaks for childcare, offered billions of dollars of new education funding, boosted health insurance and paid leave, and sent hundreds of billions to state and local governments.

The largesse represents a serious attempt at activist administration not only to try to repair the damage done by the pandemic but to remedy the inequalities that preceded and were exacerbated by it. But what is truly radical is not where the money is being spent, but how it is being raised, with politically freighted tax increases on the wealthy and corporations.

Biden has promised $2 trillion in corporate tax hikes, including an increase from 21% to 28% in the corporate rate and restoring the top individual tax bracket from 37% to 39.6%. Capital gains taxes would increase for wealthier investors, and inherited capital gains would no longer be tax-free.

In all, the package was more than twice the size of Obama’s post-financial crash Recovery Act, which spent around $800 billion. While attempts to introduce a federal $15 minimum wage as part of the act failed, Biden otherwise didn’t seek compromise for its own sake – deliberately rejecting Republican offers of cooperation for a much smaller plan. The huge act eventually passed without a single Republican vote in either the House or the Senate, relying on vice-president Kamala Harris to break the tie in the Senate to get the bill through.

Biden is planning at least one more big Congressional showdown in his first year, trying to pass an almost $2 trillion infrastructure bill, again avoiding the filibuster – a system allowing Republicans to block most bills unless the Democrats can get 60 Senate votes. The proposals use an expansive definition of infrastructure often challenged by Republicans, and would represent a second huge set of spending in Biden’s first year. The bill includes not only lots of funding for traditional infrastructure – roads and rural broadband, and the like – but also ambitious new spending for ‘social infrastructure’ – on housing, social care and so on.

In other ways, too, Biden has taken significant steps towards progressive goals: He quickly recommitted the USA to the Paris Climate Accords and the World Health Organization – both of which Trump had withdrawn from, or was in the process of doing so. He made new climate commitments for the US and has overseen an extraordinarily successful (so far) vaccine rollout.

There are interesting moves on the international stage, too, including perhaps his most ambitious so far: an attempt to achieve a global accord on business taxation, with a minimum rate on corporation tax, to weaken the incentive for multinational companies to shift their profits to places where the tax rate is lower, and minimise their responsibilities in many places where they operate. In his sights are the tech giants who are most associated with such tactics.

Biden seems on the verge of getting around 130 of the world’s countries to agree to a minimum rate, possibly ahead of this month’s G7 summit in Cornwall. Initially, this would be a fairly modest 15%, but would likely include all those G7 economies – most of the world’s largest.

The UK has said it supports this sort of idea in principle, but has been a holdout against Biden’s plan in particular. Disputes include how wide in scope it would be, with the UK keen to keep the plan just to 100 or so large multinational tech companies, but with the US wanting it to be broader in scope. Some global south countries have called for it to apply also to second-tier corporations, who often use structures to legally reduce tax when operating in those economies.

The Biden plan itself may not shake the world, but it could be an almost revolutionary foundation on which to build, creating a broad international consensus that taxation of multinationals needs to be consistent to prevent avoidance, and would be the 21st century’s first meaningful attempt at significantly reigning in the tech behemoths. If it led to rules on how profits have to be apportioned, or to an incremental increasing of the tax floor, or the eliminations of the loopholes so beloved by corporate accountants, it could become a dramatic force for change and a legacy for Biden that would far overshadow anything achieved by his recent predecessors.

It is not his only initiative that involves taking on Silicon Valley. Biden has also taken steps to encourage unionisation, just as the tech sector begins to show signs of unionising, and is pushing a “work not wealth” agenda which could put him at odds with corporate America.

Perhaps his most radical foray, when it comes to business, has been the suggestion that patent protections for coronavirus vaccines should be waived. Advocates say it would increase global vaccine production, although drugs manufacturers – a sector which traditionally provides a lot of political funding – argue that point.

When it comes to challenging vested interests, Biden seems to be as adept at it as Trump was – and is lot less gratuitous when it comes to selecting targets. Democrats who feared their party was heading into a period of directionless centrism, of an old establishment figure who would want to do nothing with his time, can be reassured that the Biden who’s moved into the West Wing seems to want to shake that reputation.

He acknowledges that his party and its voters had shifted to the left, and after years of watching a Republican Party happy to steamroller Democrat wishes to pursue their agenda, has proved unusually willing to try to do the same to push a progressive one, within the means at his disposal.

But before Saint Joe is fully canonised, there’s always that obligatory note of caution: Biden can only do so much before he hits the limits of his powers. And despite having a Democratic House and a narrowly Democratic Senate, those powers are limited.

Thanks to the intricacies of Senate rules, Biden can use the Senate reconciliation mechanism – which allows him to bypass any Republican filibuster – just two (or perhaps three, according to some Senate-watchers) times per year. Almost any other legislation beyond the scope of those is dead on arrival: even if Biden wanted to introduce single-payer healthcare, for instance, he would have zero chance.

Biden is also limited by the courts, which Trump successfully packed at all levels with ultra-Republican judges, usually young Republican judges who can expect to stay in post for decades. This is most visible in the Supreme Court, but will affect governing at all levels of the United States.

The Supreme Court narrowly voted to uphold Obamacare, for example, but now has a very different composition. Biden may find himself thwarted in the courtroom, as well as in the Senate chamber.

Progressive Democrats hardly have a worry-free life in 2021 – there are still many obstacles to them achieving their policy goals domestically and overseas. But perhaps the unexpected ray of sunshine for them is that, for now at least, the occupant of the Oval Office appears to at least be trying to deliver on their priorities. That’s half the battle.

It’s not surprising, then, that we don’t hear so much about Sleepy Joe any more. Indeed, another Republican opponent, Texas senator and presidential hopeful Ted Cruz, has hit upon another barb which seems to be more accurate. Cruz has dubbed him “boring but radical”, an epithet he’d intended as an insult but which Biden would surely take as high praise.

STORM CLOUDS AHEAD

President Biden inherited a much tougher political situation than Obama – we may have thought the US was divided by the second president Bush, but that was nothing to what was experienced under Trump, with Biden’s ascension facing an attempted insurrection on January 6, and ongoing partisan ‘recounts’ in Arizona.

But Biden’s hand in practice is weaker, too: Democrats had close to a supermajority in the Senate in 2008, and a 79-seat majority in the House. Biden’s House majority is far narrower, and his Senate is 50/50. If a single Democrat in a red state wants to stop one of his proposals, they are able to do so. Biden has no margin for error.

Those already ominous omens start to look worse when you remember what followed Obama’s landmark election in 2008: the 2010 tea party surge, which saw Republicans sweep a huge number of seats, comfortably taking control of the House and leaving the Democrats with only the narrowest control of the Senate.

Even a much smaller shift in 2022’s midterm elections – which generally favour Republicans slightly more than Democrats – could hand the modern, obstructionist Republican party control of both chambers of congress. At that point Biden’s presidency shrinks markedly, largely able only to hold back Republican legislation and respond to world events. If Biden is having his progressive moment, he may not have long in which to do it.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37