Three decades after the death of Kim Philby, perhaps Britain’s most notorious spy, CHARLIE CONNELLY ponders the changing nature of espionage

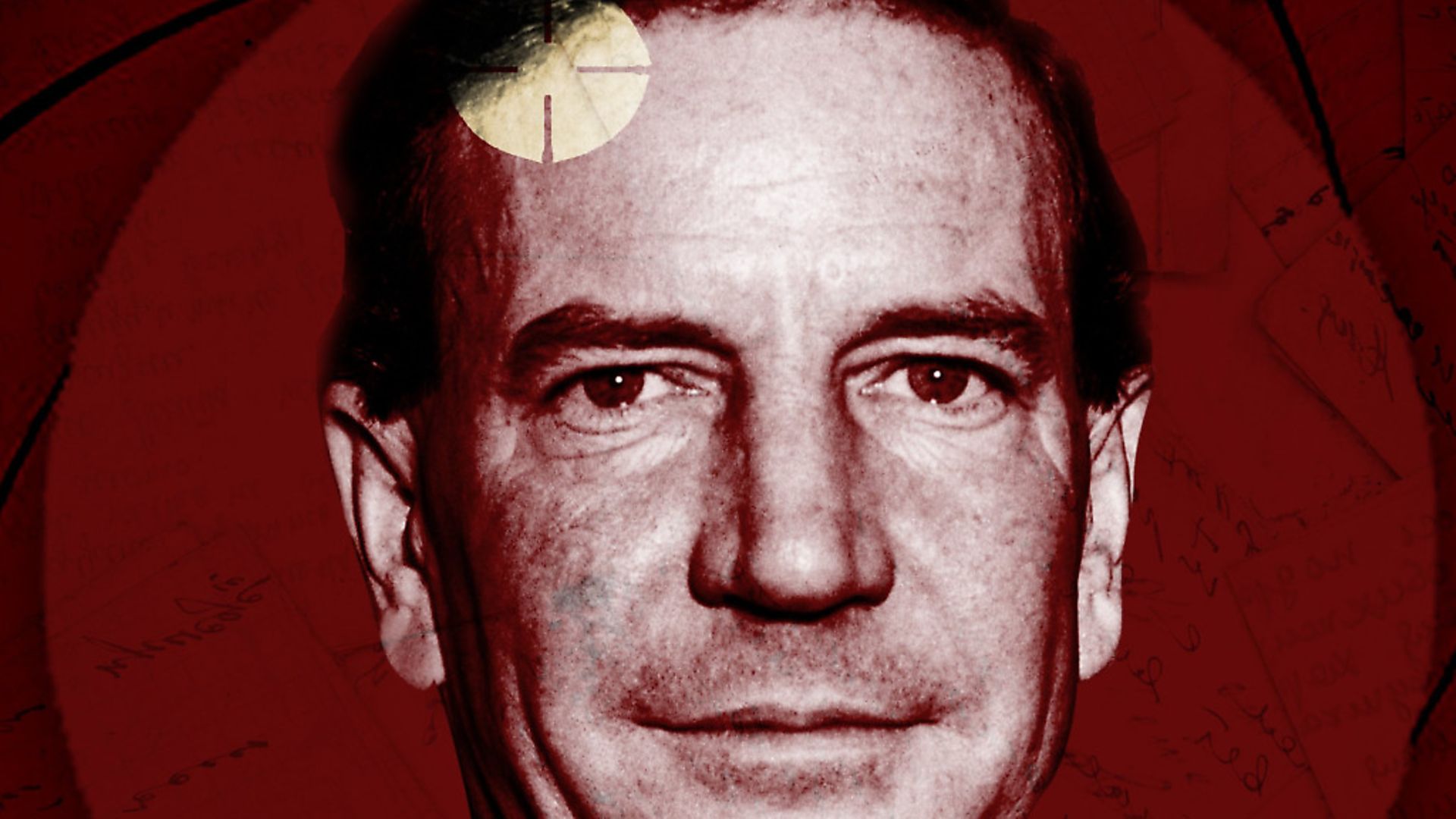

Thirty years ago this week a solemn procession made its way slowly through Moscow’s Kuntsevo cemetery on the banks of the Setun river. An open coffin draped in ruched red cloth was preceded by two enormous floral displays and placed on a red velvet-shrouded bier. Inside the coffin lay a grey-haired man with sharp features, dressed in a dark suit and strewn with red carnations. Four Soviet soldiers stood to attention at each corner as a succession of dignitaries read out tributes to ‘a man of great charm and intellect’ and ‘a great internationalist and Soviet intelligence agent’. His wife dabbed at her eyes with a handkerchief, his eldest son stood stoically at her side. The lid was placed on the coffin and three volleys of shots were fired over it. A temporary headstone displayed a photograph of the man over his name rendered in Cyrillic: Kim Philby.

It was May 13 1988, two days after the death of arguably the best known and most notorious British spy outside the realms of fiction. A member of what became known as the Cambridge spy ring along with Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross, Philby had for nearly 30 years been passing information to the Soviet Union as he rose through the ranks of MI6 until his unmasking and defection in 1963.

There was no finer illustration of the double life he led than when, having been confronted and challenged to confess by his long-term friend and fellow MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott at his home in Beirut in January 1963 Philby disappeared, failing to turn up at a dinner party. That same night a Soviet freighter, the Dolmatova, had made a hurried departure from Beirut port, casting off in such haste that it left unloaded cargo scattered on the dockside, and made for the Aegean Sea at full steam. It was heading for the Black Sea port of Odessa and its most important cargo was Kim Philby, travelling on a Soviet passport in the name of Villi Mattis but wearing a scarf from Westminster School, the exclusive pillar of the establishment where his enormous intellect had first been nurtured.

Philby’s was a classic story of Cold War espionage: furtive meetings with shady contacts, codes, microfilms, couriers and drops. Almost his entire adult life had been spent in a web of deception, mistrust and betrayal. Even when he finally arrived in the Soviet Union, for whom he had worked for many years with tireless dedication and at immense personal risk, he was kept under constant surveillance, supsected of being a triple agent for the British.

Like Burgess, Maclean and the rest, Philby was a traitor of the highest order. It is conceivable that hundreds of western agents, many of them British, are dead as a direct result of information passed through the Iron Curtain by Kim Philby of MI6. In 1949, for example, a plan was hatched to land a large group of specially-trained partisan agitators secretly on the Albanian coast in order to disrupt and undermine Enver Hoxha’s communist regime. It was exactly the kind of operation Philby would have been instrumental in facilitating. When the landing parties arrived the Albanians were waiting for them: the men were all either killed on the spot or tortured and interrogated before being executed. For all its atmosphere of gentlemen’s clubs, establishment backgrounds and honour among spies, espionage was a grubby business to put it mildly.

Unlike many of his contemporaries Philby wasn’t in it for money and he wasn’t being blackmailed. In terms of personal gain he could be said to have done very badly out of the spying business: he lived the last chapters of his life in a drab Moscow apartment far from the bespoke-tailored, country house weekends existence he was used to in London, pining for Colman’s mustard and Lea & Perrin’s Worcestershire sauce and scouring long out-of-date copies of the Times for cricket scores.

If anything could be said for Philby it’s that he at least acted out of conviction. He grew up in an age when the privileged and educated of the early 20th century saw communism first through the prism of idealism then further enhanced as the perfect antithesis of fascism. On the face of it Philby sounds an unlikely idealist but it seems he remained convinced of the purity of communist ideology from his first exposure to it during the 1930s. Even when the horrors of Stalinism were exposed he kept up his espionage on behalf of the Russian people themselves, and when he defected he was devastated to see for himself the reality of everyday life for the people of the USSR.

‘Kim believed in a just society and devoted his whole life to communism,’ said his fourth wife Rufa in Moscow after his death. ‘And here he was struck by disappointment, brought to tears. He said, ‘Why do old people live so badly here? After all, they won the war.”

Philby was an unlikely person to put his life and reputation on the line for the Russian peasantry. Born in India, public school-educated and a Cambridge graduate he seemed to be the archetypal establishment man in waiting. After graduating he went to Vienna in 1933 with an organisation providing relief for refugees fleeing the Nazis. There he met and fell in love with Litzi Friedmann, a communist from a Hungarian Jewish family. After the assassination of the Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss and a rise in Austrian anti-semitism the couple decamped to London where, possibly through Friedmann’s connections, he was first brought into the spying fold after a clandestine meeting with a man calling himself ‘Otto’ in Regent’s Park.

He covered the Spanish Civil War as a journalist for the Times where he found himself sending information about the German weapons technology on display to both the Russian and British secret services, commencing the duplicitous existence that would define the rest of his life while being decorated by Franco into the bargain.

By 1941 he was fully ensconced within MI6 and charged with feeding dummy information to the Russians through double agents in a period when his underlings included Graham Greene and Malcolm Muggeridge, the latter describing Philby as ‘a real-life James Bond. His boozy amours, his tough postures, his intelligence expertise, are directly related to the same characteristics of Fleming’s hero’. All the while, of course, Philby was feeding information about British agents to the Russians, something he continued after the war when he was put in charge of counterespionage at MI6 based initially in Istanbul and then, from 1949, in Washington. For this work Philby received the OBE.

Almost exposed when Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were blown in 1951 – something he’d fought hard but unsuccessfully to prevent – Philby came under enough suspicion of being the ‘third man’ involved to force his resignation from MI6. Despite intense questioning by MI5 he wasn’t compromised and in 1955 was even publicly exonerated by the foreign secretary Harold Macmillan.

Returning to journalism he relocated to Beirut as a correspondent for the Observer and the Economist where he continued surreptitious work for British intelligence but, without access to information of value to the Russians, became a dormant KGB asset.

He may well have escaped exposure were it not for the defection to the USA of a high-ranking KGB officer named Anatoliy Golitsyn in 1961, who told the western allies enough to compromise Philby and necessitate that escape by sea to Odessa with his fake Soviet passport and Westminster School scarf.

The 30th anniversary of Philby’s death comes soon after the attempted assassinations of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Salisbury and among the seemingly incessant instances of fake news and computer hacking that suggests the world has moved on from espionage to simple international trolling. Today we live in a world that’s not so much a battle of ideologies as technologies.

In Philby’s day the great powers butted heads largely in secret, eyeing each other suspiciously across the faultline of the Iron Curtain while people in attics furtively tapped out coded messages and shifty men in trench coats left microfilms for each other in the branches of trees and behind loose bricks. Today the Russian Embassy in London can tweak the nose of the British government with a tweet that’s seen by thousands of people a heartbeat after it’s sent. A rolling news channel beams Russian state-sponsored takes on current affairs into our living rooms. North Korean hackers can bring the National Health Service almost to a standstill by releasing ransomware from laptops in Pyongyang. The German government’s intranet system can be compromised and information about military movements spirited away to who knows where via wifi. Entire national elections can be influenced by posting fictional news stories and dodgy adverts on a website full of cat pictures and people listing their ten favourite albums.

But what is all this trying to achieve? What ideologies would a Kim Philby of today cite in support of treason? The quest for a sizable Twitter following?

‘Our work does imply getting dirty hands from time to time,’ Philby said after his defection, ‘but we do it for a cause that’s not dirty in any way.’ Who could claim that today? People plopping polonium into teacups in posh hotels, or smearing nerve agents on door handles in market towns?

As Philby’s fictional counterpart James Bond put it in Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, the first Bond novel, written in 1952 a few months after Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean had absconded: ‘This country-right-or-wrong business is getting a little out-of-date. Today we are fighting communism. Okay. If I’d been alive 50 years ago, the brand of conservatism we have today would have been damn near called communism and we should have been told to go and fight that. History is moving pretty quickly these days and heroes and villains keep on changing parts.’

Putin himself comes from a secret service background: he was a career KGB officer and would have been one during Philby’s Moscow years. Who knows, he might even have been in the long line of mourners behind the coffin on that sunny spring day 30 years ago.

While the ideology they both served may have lost the Cold War, Putin is happy enough to associate himself with Philby today.

At the end of last year the Russian Historical Society – a state-sponsored organisation – staged an exhibition in Moscow called Kim Philby: The Spy And The Man. With its displays of secret British documents Philby had sent to Moscow, his armchair, briefcase, pipe and the hefty old radio on which he would have tried to tune in to the BBC World Service to catch the test match scores, Philby is being marketed to modern Russians not as a communist idealist but a Russian patriot. Around the same time a painting of Philby was unveiled in a Russian national gallery and a documentary film of his life aired on television. The old spy is being rebranded to reinforce the authority of the Russian regime, a regime he would in all likelihood have despised. This is, after all, a man who when asked by his third wife Eleanor which he’d choose if push came to shove, family or the Party answered, ‘the Party of course.’

The commandeering of Philby by the Putin regime provokes questions about the nature of espionage and even the nature of treason. The 30th anniversary of his death certainly doesn’t make one pine for some kind of mythical golden age of espionage: people died as a result of what Philby and his fellow Cambridge spies did. People aren’t landing in secret coves at the dead of night any more, or lurking in shop doorways pulling hat brims down over their eyes, they’re sitting in basements with laptops creating Twitter accounts and hacking into government infrastructures as a coffee machine gurgles in the background.

Espionage today is more about USB ports than Black Sea ports. Borders are no barrier: modern deception is played out in plain sight on screens and through servers. Treachery is much easier to pull off with 280 characters and a password.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37