Responses to the bombing will be a test of the resilience, maturity and cohesion of both society and party leaders

The nihilistic horror of the Manchester Arena bombing threatens to suck much of the already-thin air out of Britain’s election campaign, whether or not that was the solipsistic perpetrator’s intention. Tax rates, Theresa May’s U-turn over social care provision for the elderly, even the Brexit negotiating mandate for which May’s ‘Me Election’ was ostensibly called, suddenly they look trivial when set against a brutal act of mass murder.

But they are not. Dreadfully real though it now feels, it is the bombing which, for all but the victims grieving loved ones, is ephemeral unless society chooses to over-react. That may have been suicide bomber, Libyan Mancunian, Salman Abedi’s intention too.

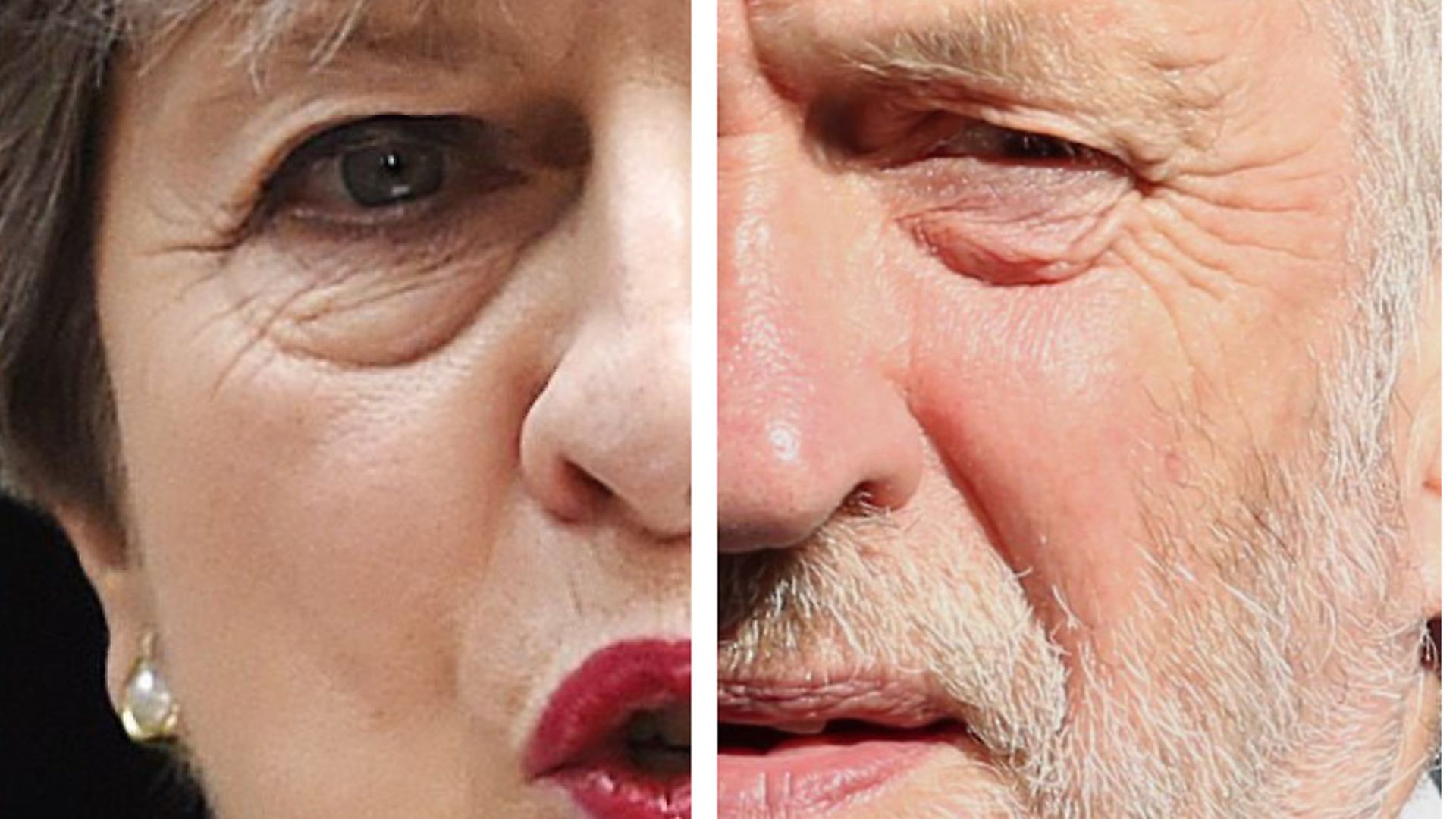

But if such wanton acts of violence against teenage girls test society, its resilience, maturity and cohesion – Monday’s attack prompted countless acts of kindness and solidarity – they test political leaders far more acutely. Their responses impact much more in an election campaign where those voters who rarely bother with such matters are paying as much attention as they are ever likely to pay. The tone party leaders adopt and the actions they propose to make citizens both feel safer and be safer – not necessarily the same thing – can make or wreck careers. A crisis can be defining. Emerging from chairing COBRA, May put troops on the streets in case a sophisticated bomb maker is now at large, the first time since 2003. Decisive action or gesture election politics? Voters will decide. The wilder shores of social media insanity think the whole incident an ‘Establishment’ plot or call (Katie Hopkins) for a ‘final solution’. Let’s ignore them.

Of course, the bombing should not change the shape or focus of the campaign. Britain and Ireland have lived with varying degrees of home-grown terrorist outrage since the Irish Troubles re-ignited in the 70s, prolonged since Islamist violence filled the void created by the Good Friday Agreement. We may be resentful, but we are also resigned. Thanks to good police and intelligence work – plus mostly responsible politics – we have been lucky since 7/7 twelve years ago; certainly far luckier than our French neighbours, so similar in their problems, so different in their response: British multi-culturalism – communautarisme – versus the French doctrine of secular Republican égalité.

To their credit French voters did not let the murder of a policeman in Paris upset the focus of last month’s election. Though it could have – perhaps did – generate more votes for Marine Le Pen, it may also have prompted more French citizens to reject her brand of intolerance too, her outlandish, Trump-like remedies, divisive and futile. Nowhere is the intellectual battle to explain ‘home grown’ jihadi suicide bombers like Abedi fiercer than in France. Scholarly political scientist Gilles Kepel is on Islamist death lists for scorning racism and Islamophobia as left wing explanations for such violence – ‘Islamo-gauchism’ he calls it. Kepel critics like Olivier Roy counter that the core French doctrine of secularism – laïcité – is too rigid and should become more tolerant of diversity and its symbols, including those banned hijabi head scarves. The suicide model of jihad is a youth cult, Roy argues, rooted in a wider generational revolt among the angry, disaffected young, along with pop music and sport. Though jihadis – ‘evil losers’ in Trump-speak – latch on to Islam, they know little about it. Violence is an end, not a means.

As Britain again examines the effectiveness of successive governments’ Prevent strategy and budget priorities, we can recognise a homely British version of that debate in the writings of David Goodhart, Douglas Murray, Trevor Phillips and others. But election campaigns are mostly tactical, not philosophical. That is especially so when the chief protagonist, prime minister May, is seen with increasing clarity as a leader without deep analytical powers or inclinations, a pragmatic provincial conservative who responds to the pressure of events by changing her position. ‘Weak and wobbly’, cries Channel 4’s News’s mischievous Michael Crick in the wake of the social care U-turn. A caring leader who ‘shows she’s prepared to listen to all the arguments before a decision is made’, counters the Daily Mail, even more brazen than Crick.

In the short term it’s obvious that Abedi’s crime will play to former home secretary May’s strengths, perhaps to those of ex-health and culture secretary, Andy Burnham, now Manchester’s new metro-mayor. He has been given a chance to show bold and sensitive leadership of a city which turned the 1996 IRA Arndale shopping centre bombing – 200 injured by the 3,300 pound explosion, but no one killed thanks to a warning – into an opportunity to reshape its retail centre. Good can come of evil. It is also painfully obvious that the newly reshaped election narrative does no favours to Jeremy Corbyn, whose armchair support for a range of terrorist-related organisations was being ploughed up by the Tory tabloids even before the Manchester massacre. Unfair perhaps, but unfortunately also true. The Labour leader has long been naively selective in what he presents as his bridge-building for peace and in his declared abhorrence of violence. John McDonnell’s position is even shakier.

Blame by mere association, whether directed against the ambiguity of Labour politicians or against the wider British Muslim community, is always wrong. It was right – on that occasion even those Tory tabloids agreed – not to blame the hate-filled murder of MP Jo Cox by the violent right-wing nationalist, Thomas Mair, on the raucously nationalist thread in the Brexit campaign which it interrupted. So it is right now to place the blame for the massacre of young Ariana Grande fans at the perpetrators’ door: he or they who inspired, planned and perpetrated this crime against what they dismiss as corrupted adolescents.

When the immediate outrage subsides, giving way to forensic inquests and patient police work, we will still face critical June 8 decisions on May’s mandate for the Brexit talks. The EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, now confirms it will start (with that cash settlement, he still insists) on June 19.

Great issues of taxation and expenditure – the parties further apart than they have been for 30 years – must be addressed in terms of the dispiriting question: ‘Whose version do we disbelieve the least?’ The elderly will still be getting older – two million more over 75s by 2030, so May reminded the BBC’s Andrew Neill in her distinctly lacklustre interview (I got that wrong here last week) hours before the Manchester bombing.

In that sense the bomber did the Tory campaign a considerable favour. Early editions of Tuesday’s newspapers – plus my late edition of the FT – were full of ‘May’s dementia tax’ chaos on their front pages, a row rapidly demoted to old news. Corbyn’s last minute ‘offer’ – bribe? – to students (I’ll cancel next autumn’s tuition fees if you can remember to register and vote for me) made earlier in the day had already been overwhelmed by May’s retreat on social care. Did it work, all the same? Some 620,000 people registered on deadline day, a quarter of them under 25.

Neither leader’s policy tweak was a good advertisement for the campaign process, half-baked, expedient and not seriously costed, let alone shown to be practicable. The Labour leadership can claim that its post-Miliband swing to the left has already closed the gap – down from a 20% Tory lead to barely double figures before Manchester – and will be vindicated on polling day by exceeding Red Ed’s 30.4% share of the vote. The contours of a ‘Jeremy Must Stay’ campaign are already visible. But a ‘Wobbly Wednesday’ moment is usually part of a winning Conservative campaign, seized on by a grateful media which needs to have some kind of horse race to sustain reader interest. The idea that the Tories might lose (‘I only have to lose six seats to lose’, May tweeted) is also a useful reminder that loyalists must not stay at home. ‘Remember how complacency made the Brexit result go wrong,’ pro-Remain’s May might add. But that’s an argument Brexit’s Theresa daren’t use, isn’t it?

With every day that passes I stick more closely to my working hypothesis that Labour’s strange campaign – I have yet to hear of a constituency flier carrying the leader’s photo, it’s all local – is designed to shore up Corbyn’s grip on the party machine, not to win power. It’s a core vote, feel-good campaign, vaguely intended to give hope without a serious price tag or prospect of being called upon to implement promises. Many activists will be happier to lose than they admit, ‘pure but impotent’, as Aneurin Bevan used to put it, in self-imposed opposition too. Whether such people will still be in a majority in the small hours of June 9 is the crucial question. Thoughtful voters may not think much of Tory maths, but they trust Labour’s even less. In the present climate waverers are like to opt for Scrooge, not for Santa, for the Frugal Housewife over the Tree Grown Theory of Money.

As so often in 2017, Labour’s failure (and the Lib Dems, stalled and fearful of net losses) places added burdens on May’s slender shoulders. In the process of accelerating the marginalisation of Corbynite Labour she has also marginalised most of her cabinet. Deemed to be relatively safe hands, Damian Green (a friend from Oxford days) and Jeremy Hunt were let out on licence to defend the social care package 1.0. They stand damaged as a result. It was the version which had to be junked just days later, making their explanatory quotes evidence for the prosecution case. When May said ‘nothing has changed’ after her U-turn, the vicar’s daughter lied. Corbyn may initially have got the details wrong – it was a £100,000 floor on individual costs, not a £100,000 cap, Jeremy – but the charge that he was promulgating fake news to frighten the elderly simply wasn’t true.

The incident tells us – and Michel Barnier – a lot about the May operation and most of it isn’t good. The roughly established narrative is that a good intention lurked behind the 1.0 version of social care, namely a willingness to face up to an urgent problem which politicians like Dave and George have ducked for too long: the cost of caring for the frail elderly and (overlooked in the row) the unaffordability of some OAP perks shared by older dukes who use the winter fuel allowance to warm the east wing. Means-testing the WFA might save £1.7 bn, though eliminating the third ‘triple lock’ on state pensions – no 2.5% increase if prices or wages don’t exceed that figure – won’t save much in the short term. Prices, alas, are likely to do so.

But it was signal of willingness to take unpopular decisions, taken from the safety of a 20% poll lead. We are told that ex-City man John Godfrey, head of No 10’s policy unit, was wary of proposing the £100,000 floor on costs an individual might be required to contribute without also imposing a ceiling. It might perhaps be higher than the £72,000 proposed by the cerebral statistician, Sir Andrew Dilnot – the sort of official Emmanuel Macron is putting in his new French cabinet – in a report accepted, then shelved by the Cameroons. Without a cap there is too much of a lottery and no incentive for middle class voters with much to lose to seek private insurance which the City has been slower to develop than its Japanese counterparts. In Japan such saving is now compulsory.

As such, Britain’s unreformed system is unfair, not so much a ‘dementia tax’ on the minority of older voters cruelly afflicted by loss of mental faculties – even the lofty FT used the Labour-coined phrase – as a ‘dementia lottery’. The NHS remains free at the point of use, as it was in 1948. Social care never has been, though the distinction can be an artificial one. Currently those with assets less than £23,000 are spared the cost of care in their own homes (though some hard-pressed councils are still more generous or less efficient in collecting dues). It is a perk that May’s manifesto still proposes to withdraw, to equalise their situation with those needing residential care.

As for those care home residents, those with substantial assets are often charged more for their weekly stay than councils pay for those they fund. In effect, better-off pensioners subsidise the council’s clients, through fees, not taxes. Not that £600-£1,000 a week per resident is cheap for either party. Nor is it surprising that care homes (burdened by falling council revenue and by debt from hedge fund property scams) are going bust. Most of us die from other causes and more quickly. But we all know friends with two elderly parents each needing full-time care. In prolonging life so brilliantly society is creating financial and ethical burdens which make Brexit look simple.

What seems to have happened is that Nick Timothy, May’s bearded joint chief of staff, a man described as ‘brilliant’ by some Whitehall insiders, decided that a grand gesture of inter-generational solidarity would drop the Dilnot cap and let ageing baby boomers – the lucky generation – pay for most of their own care. Obviously it would hit the Tory voting comfortable middle class harder than the Just About Managing JAMS – a bonus for the ‘red Tory’ which lurks under Timothy’s beard. He claims to have read everything written by Lord Glasman, theoretician of ‘Blue Labour’. Insiders claim the bearded one will effectively run Britain while the boss concentrates on Brexit.

Timothy’s social policy 1.0 was fine in theory, even brave, but lousy politics, as Tory backbenchers, cabinet ministers even, could have told Team May if they’d been consulted. May’s insistence that a cap would have been included in due course cuts little ice with anyone but diehard loyalists. It shows that she takes too much advice from too few people with too little experience of policymaking at the highest level or across a bandwidth wider than the introverted Home Office. The U-turn shows Barnier, among others, that she will buckle under pressure, that beneath that coolly reserved exterior lies, not another Iron Lady but a Plastic one. On Brexit, on Hinkley Point (delayed, then authorised), the British Bill of Rights and workers on boards, on energy caps and foreign worker lists, May makes promises she later modifies.

At least Philip Hammond, forced by No 10 to drop his perfectly reasonable budget increase in NICs paid by the self-employed, may now feel more secure in his job – days after the PM conspicuously failed to say her chancellor would remain in post on June 9. Events are conspiring to weaken May’s ‘Me or Corbyn Mandate’. With Salman Abedi’s witless help she may trounce Corbyn and get that three-figure Commons majority, though I still doubt it. But her nervous body language on public platforms and in (rare) television interviews is telling voters and her new MPs that the lady is for turning.

If there is any consolation for May, as she contemplates the irony of a grim political week being rescued by a far grimmer atrocity in Manchester, it is that the Tory tabloids showed they are for turning too. Like ‘death tax’, the glib phrase that helped kill Labour’s last effort to tackle elderly care in the 2010 campaign – it was actually Mayor Burnham promoting it – ‘dementia tax’ is a crude, emotive label designed to shut down rational debate. Tax-shy newspapers owned by oligarchs are keen to minimise inheritance tax and maximise inheritance for obvious reasons, though death gets even oligarchs in the end.

But their shameless glossing over of Team May’s failure on social care serves to remind just what cynical contortions they are prepared to inflict on readers if a prime minister can square or squash them. Might that offer a glimmer of hope if Team May can raise its game and deliver a half-decent Brexit deal?

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37