As a new blockbuster exhibition opens at the British Museum, FLORENCE HALLETT explores manga’s global appeal.

In our multi-platform, digital world images are everything, and manga – Japanese comics – are the lingua franca. In the west, a niche interest largely restricted to adolescent and teenage boys has become mainstream, and today the UK is Europe’s fastest growing market for manga.

The action hero mangas that first sparked the imaginations of western boys reared on Japanese animations (anime) like Pokémon and Dragon Ball have been joined by an ever-broadening range of subjects, including sports and history, fantasy, romance and horror.

Today, we’re all schooled in manga whether we know it or not – the kitsch and creepy LOL Surprise! dolls beloved of primary-aged girls feature the big eyes typical of manga style, while its codified facial expressions are familiar to anyone who has ever used an emoji.

Not surprisingly, manga is ubiquitous in Japan and its dynamic, graphic style makes it the medium of choice for state and corporate communications. Government posters, especially those aimed at foreigners, are couched as manga, as well as advertising, school textbooks and public information posters such as the Kyoto Municipal Transportation Bureau’s Let’s Take the Subway! poster (2013-18).

For Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, curator of the biggest exhibition of manga ever staged outside Japan, the timing of the British Museum’s summer blockbuster couldn’t be better.

Even in the three years that have passed since she began planning the exhibition, manga has blossomed in the UK, with major bookshops doubling their range, at least.

Even so, the choices available in Britain fall far short of the array of subjects and styles found in Japan where manga is enjoyed by audiences old and young, male and female. “There is such a richness in expression, it makes you realise manga is very vital,” she says, and through loans from some of Japan’s best-loved manga artists, a recreation of a Tokyo bookshop, and free digital downloads, the exhibition aims to give British audiences a flavour of manga as it is enjoyed in Japan today.

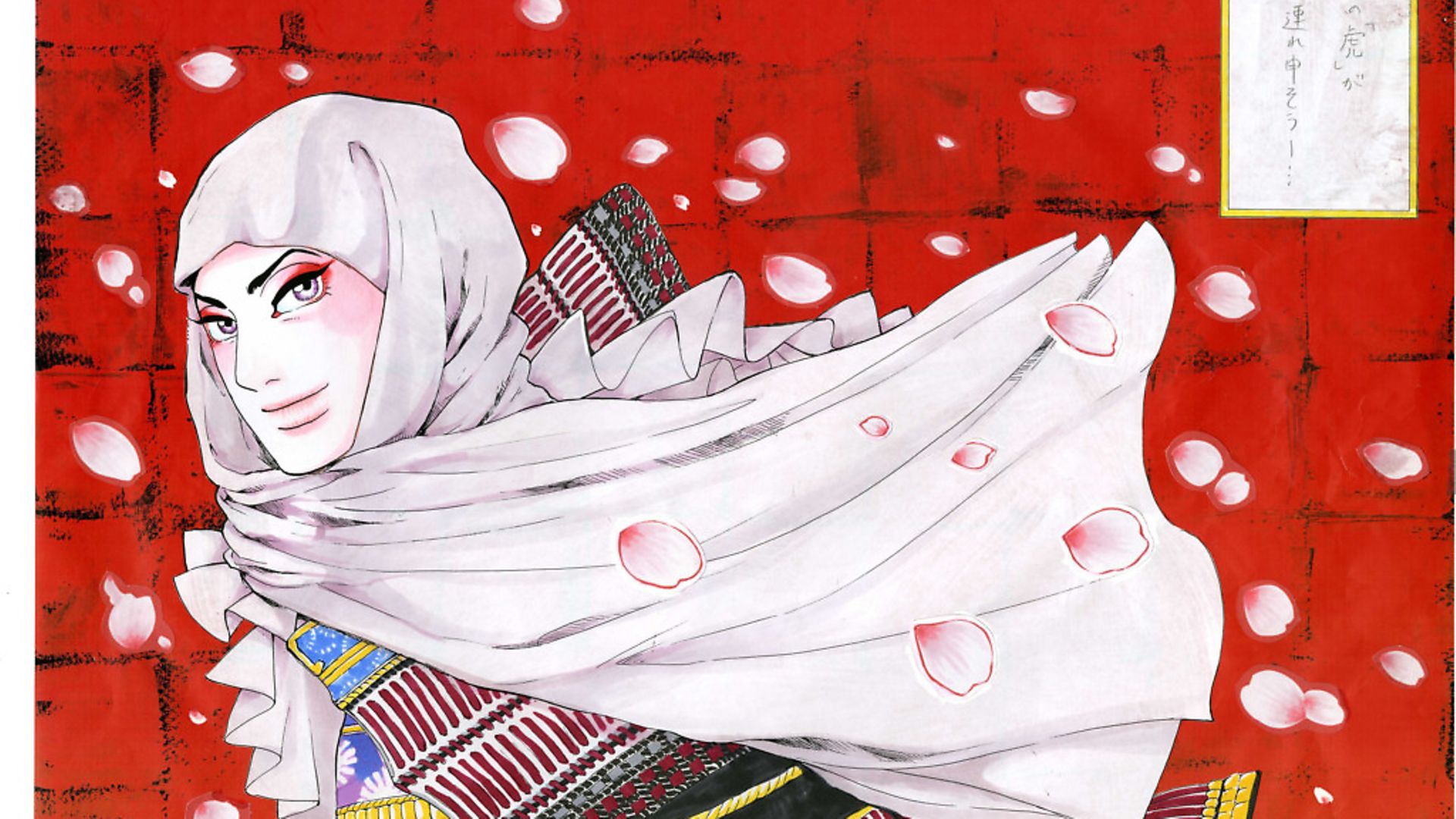

“There is a manga for everyone”, according to Rousmaniere, and as its popularity grew in the decades after the Second World War, the action and adventure stories of shonen manga, aimed at teenage boys, were joined by shojo, aimed at young women and typified by complex characterisations and an emphasis on human relationships.

As an immersive form of visual storytelling it’s an art form well-suited to 21st century conditions, says Rousmaniere: “It feeds an international audience hungry not just for pictures but for stories.”

Consequently, it keeps on growing and is now a multi-billion dollar, international industry, that has expanded beyond the confines of print media to include anime, fashion and street art as well as gaming and digital multimedia.

Roughly translated as “pictures run riot”, manga has its roots in 12th and 13th century handscrolls in which narrative scenes combine text and images. It first appeared in the form we know it today in the 19th century, serialised in newspapers, but the term ‘manga’ was first used in the 18th century to describe collections of unrelated and spontaneously drawn scenes, figures and animals published in volumes.

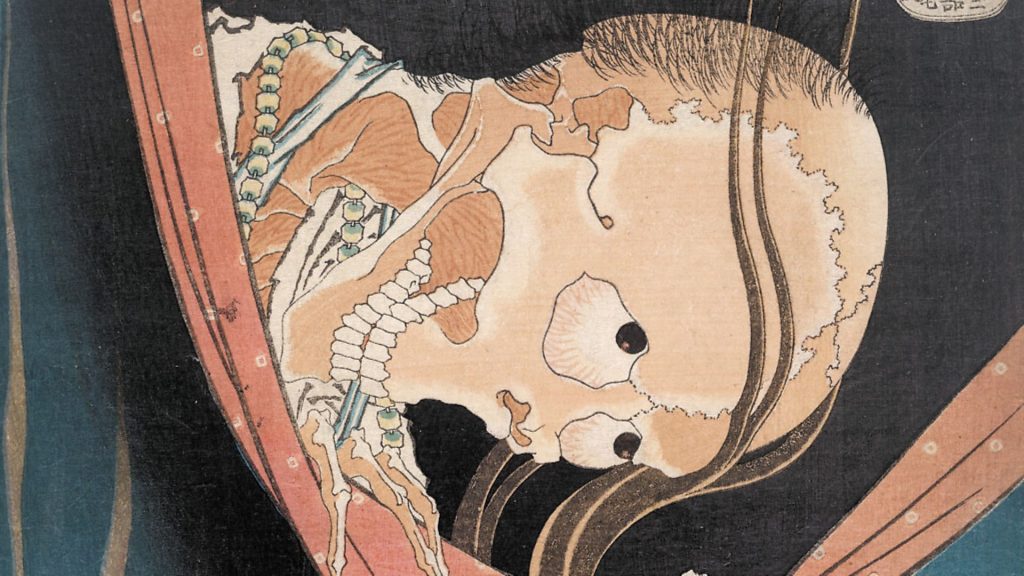

The most famous example was made by Hokusai (1760-1849), Japan’s most celebrated artist: the Hokusai manga was a woodblock-printed illustrated book intended as a drawing manual for students, and was so popular that it remained in print for almost a century.

Though Hokusai manga is not manga in the sense it is understood today, Hokusai’s work, specifically his cast of fantastical characters such as Kohada Koheiji, and his original approach to visual storytelling, has undoubtedly had a significant influence on manga artists.

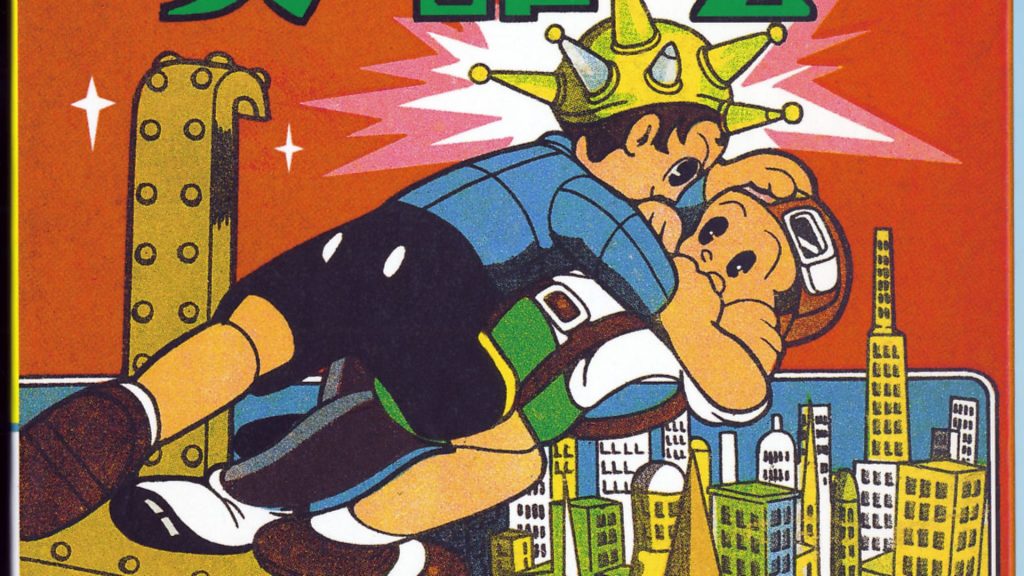

Manga’s sources extend far beyond Japanese culture, however, and have tended to reflect Japan’s relationship with the wider world. The style and content of mangas produced immediately after the Second World War show the influence of American comics and films which were readily available during the post-war occupation of Japan by the USA.

The end of occupation brought a broadening of subject matter, and artists began increasingly to aim at a more adult audience and to consider the traumatic events of the war, with several artists tackling the experience and aftermath of the atomic bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In 1949, Fritz Lang’s classic German expressionist film Metropolis inspired a manga series, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland has been the subject of numerous manga adaptations since it was first translated into Japanese in 1899.

For Keiko Takemiya, one of the generation of women artists known as the Year 24 Group which transformed manga in the 1960s and 1970s, Alice in Wonderland emerged as a symbol of female creative resistance.

Her mangas, Alice Book I and Alice Book II, have little directly to do with Lewis Carroll’s story, which instead serves as the framework for an unfettered fantasy world that contrasts with the constrained world imposed on women artists by their male editors.

Today, around half of manga artists are women, which corresponds to the huge market for shojo (girls’) manga, not just among its target demographic, but with males readers too.

In introducing subjects like gender identity and friendship – specifically the close male friendships that make up the sub-genre ‘boys’ love’ – shojo manga has attracted a new and growing audience with stories that explore human relationships and emotions in a sympathetic and inquiring way.

Though in so many respects progressive and open to fresh ideas and forms, manga remains in many fundamental ways conservative. Despite its growing international audience, it has resisted any pressure to adopt western practices, and most manga retains the traditional Japanese right to left page order, which is echoed in the reading order of story panels.

Despite its position at the interface with digital technologies, manga’s hand-drawn quality continues to be essential to its character and appeal, with some artists continuing to use the traditional Japanese brush and ink method.

While western cartoon strips tend to treat text and image as separate but equally important narrative elements, in manga the image leads the narrative, a hierarchy that follows on from the Japanese writing system, which requires the interpretation of pictorial elements.

It is sufficiently developed that an established lexicon of symbols – manpu – exists to indicate sounds, feelings and specific movements, which appear in story boxes as part of the illustration. Kono Fumiyo’s Giga Town: A Catalogue of Manga Symbols, 2017, explains their usage in a retelling of Handscrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans, one of Japan’s most venerable texts.

An arc with dashes across it indicates “cheering with excitement”, a star between two characters “indicates that two pairs of eyes are locked in opposition or a state of hostility”. A shallow spiral, as seen here underneath the character of Mimi-chan, the white rabbit, “indicates a state of running at full speed”.

Conventions such as these place no restrictions on creative freedom however, and artists – mangaka – are celebrated for their individual styles. Even so, manga production is a complex, collaborative effort, with most artists employing a team of assistants, and working under an editor whose job it is to shape the development of a storyline as well as to supervise and approve drawings.

Its not just artists and production teams who decide a storyline, and the interaction between fans, artists and characters has long been an important element of manga, with readers’ comments published in magazines, and artists and readers corresponding via fan clubs.

Many readers draw manga themselves, creating alternative narratives for existing characters, an activity that allows them to be ever more immersed in their preferred manga world.

These fan mangas (dojinshi) can be successful in themselves, and some sense of the thriving market for them is indicated by the success of Comiket, a huge comics market that began in 1975.

Comiket is held in different locations around the world, and twice a year in Japan where it attracts more than half a million people. Fans’ desire to immerse themselves in their chosen fantasy world has also seen the rise of cosplay, events where fans get together to celebrate their favourite characters by dressing up, often with extraordinary attention to detail.

Opportunities for readers to become ever more involved with characters and storylines are on the rise as manga is increasingly conceived as part of a ‘media-mix’, launched across a range of platforms, from traditional books to electronic publications, to video games and anime. It’s a strategy typified by the Pokémon franchise, which since its launch as a Game Boy video game in 1996 has extended into almost every area of popular culture, from films and television, to trading cards and of course manga.

– Manga runs at the British Museum until August 26, 2019

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37