CHARLIE CONNELLY takes an in depth look into the life of the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and pioneer researcher Marie Curie.

Marie Curie was destined to be an outsider from the day she was born into a fractured, occupied and oppressed nation. The struggles of her native Poland and the patriotic Warsaw family into which she was born came to mirror the lack of acceptance and recognition she would receive for her groundbreaking work. Curie’s discoveries would have been extraordinary enough had they been made by someone with the advantages of gender and background, not to mention her living and working in a country in which she endured intense periods of hostility. Yet despite consistent snubs and setbacks her work in the field of radioactivity made her the first woman to win a Nobel prize, the first person to win a second Nobel prize and the only person ever to win in two different disciplines, all for discoveries that can genuinely be said to have changed the world.

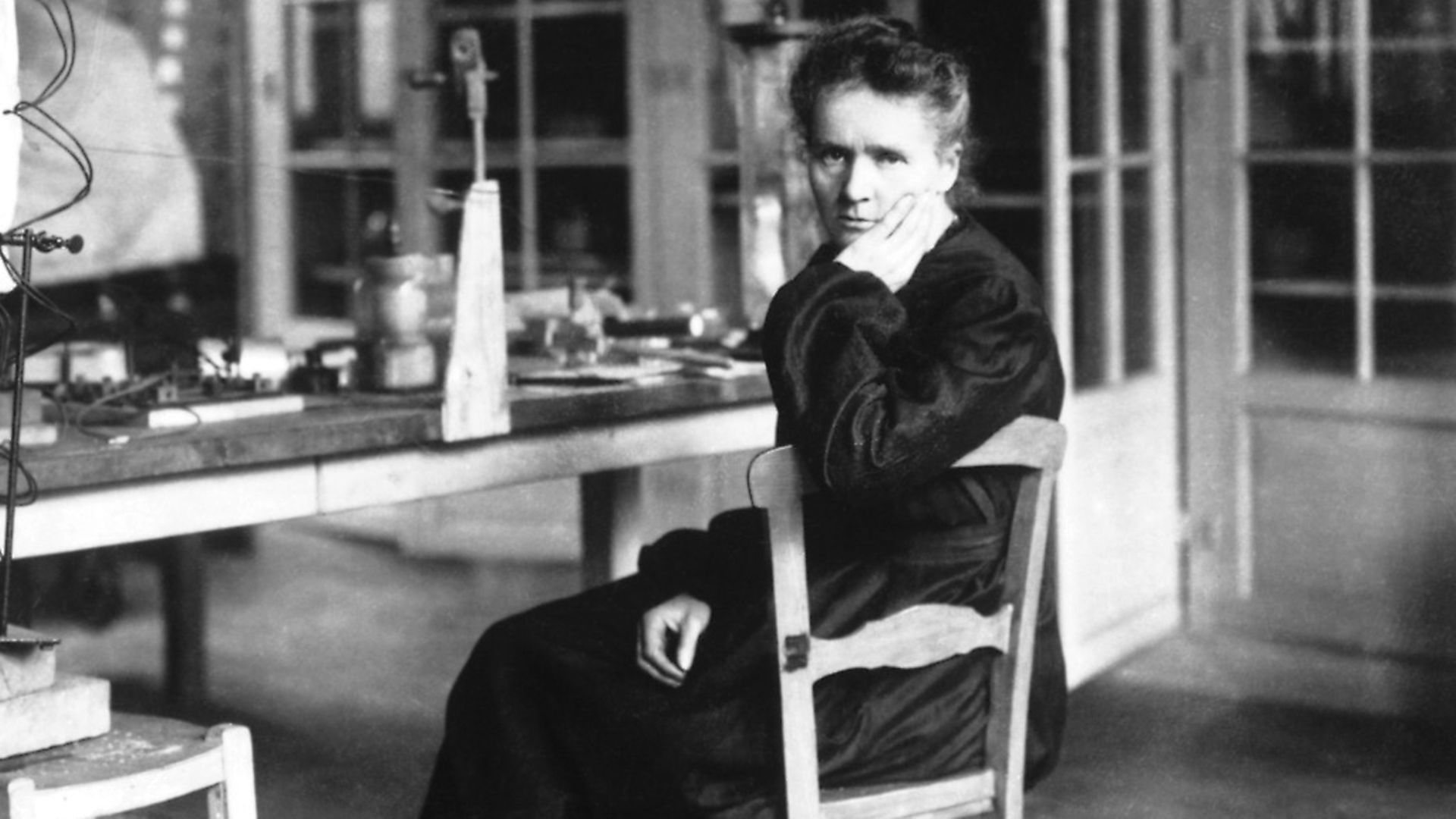

When Curie discovered the emission of rays by uranium compounds were an atomic property of the element uranium she revolutionised science. Until then physicists had been convinced the atom was indivisible as the smallest elemental component. Curie’s work proved otherwise, allowing her to isolate and identify polonium and radium and transform the entire mindset of science through research carried out not in a hi-tech laboratory but in a damp storeroom using borrowed apparatus.

When she was born the youngest of five children to schoolteacher parents there was no inkling that Maria ‘Manya’ Sklodowski had anything ahead of her but the aspiration-devoid life of a lower-middle class Polish woman. The nation was divided territory and had been for a century, split three ways between Austria, Prussia and Russia, with the Sklodowskis living under tsarist rule. Manya came from a long line of Polish patriots and the once well-to-do family had already lost their home and lands as a result of their involvement in decades of agitation against the ruling Russian empire. Her father Wladislaw was a maths and physics teacher whose well-known Polish nationalist sympathies eventually cost him his job, reducing the family’s circumstances further. Once his wife Bronislawa died after a five-year battle with tuberculosis when Manya was just 10 the family faced further hardship.

Despite these straitened circumstances Manya was determined to take her studies as far as she could, finding work as a governess on leaving school in order to save enough money until she was able to join her sister, also named Bronislawa, in Paris at the age of 24. Enrolling to study physics, chemistry and mathematics at the Sorbonne, she met fellow physicist Pierre Curie and became his student.

Eight years her senior and already a rising star in the world of science Pierre was soon smitten with the intense, determined Pole, even referring to her as his muse, and, after a short romance, proposed marriage. Marie – she had adopted the French version of her name soon after arriving in France – turned him down as on completing her studies she planned to return to Poland. But when her application to embark on a doctoral degree at the university in Krakow was rejected because she was a woman, she changed her mind: Paris became her home, Pierre became her husband.

Curie specialised in the x-ray potential of uranium rays, picking up the baton with Pierre from earlier work by the French physicist Henri Becquerel and leading to the discovery in 1898 of the element she named polonium in honour of her embattled home country. Six months later came the discovery of radium from research in which the Curies first coined the term ‘radioactivity’.

For all her dynamism and brilliance Marie still found recognition hard to come by. She never complained, preferring to concentrate on the work itself. “Life is not easy for any of us, but what of that?” she said. “We must have perseverance and above all confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something and that this thing must be attained.”

The snubs mounted, however. When the Curies were invited to address the Royal Institution in 1903 Marie was not allowed to speak. In December the same year she became the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize, sharing it with Pierre and Becquerel, but even then it took lobbying on the part of her husband and committee member Magnus Gosta Mittag-Leffler to add her name to the physics award. Pressure of work meant that it would be two years before the couple could travel to Sweden to give the traditional lecture which Pierre had to deliver alone, although he was sure to heap praise upon his wife. When, three years after the Nobel award, Pierre was killed falling under the wheels of a carriage while crossing the Rue Dauphine in Paris, Marie lost her husband, her closest scientific confidant and her most passionate advocate.

Despite her spectacular successes Curie was destined to remain an outsider in Paris, as a woman in the field of science and as a Pole in France. The French press was particularly hostile, notably in 1911 when she was put forward for membership of the French Academy of Sciences against the popular wireless telegraphy pioneer Edouard Branly, whom many in France felt should have been awarded the 1909 Nobel Prize for physics given to the charismatic Italian Guglielmo Marconi. In the run-up to the election Curie was condemned by sections of the press as a foreigner and an atheist with some newspapers employing anti-Semitic tropes against her despite the fact she wasn’t Jewish, part of a smear campaign that prevented her election to the Academy (it would be another 50 years before a woman was admitted, a former doctoral student of Curie’s).

Later that year she was awarded her second Nobel Prize, for chemistry, in recognition of her pioneering work with radium and polonium. Before the award could be presented the French media learned of the relationship she had begun with fellow physicist Paul Langevin, who was at the time estranged from his wife. Curie was lambasted by the media and labelled a home-wrecker who had desecrated the memory of her husband. One newspaper even alleged the relationship had begun while Pierre was still alive and suggested his death had been the suicide of a heartbroken man.

When she returned from the prize-giving in Sweden, Curie found an angry crowd gathered outside her house, forcing her and her children into hiding at the home of a friend and helping to trigger a breakdown that, coupled with a kidney complaint, kept her away from her work for 14 months.

Curie had recovered enough when war was declared to throw herself into providing mobile and field x-ray units for the benefit of wounded soldiers at the front, making bullets, shrapnel and broken bones easier for medics to locate. With 20 trucks known as les petites Curies and 200 x-ray machines distributed to field hospitals across the European theatre, some estimates put the number of wounded soldiers aided by Curie’s efforts at more than a million.

Assisted by her teenage daughter Irene, Curie toured hospitals and drove the trucks across the mud and shattered duckboards, working tirelessly and fearlessly for the welfare of the wounded soldiers of their adoptive homeland. So dedicated was she to the French war effort that in addition to her work she even offered the government her gold Nobel medals to melt down. Despite her heroics and selfless dedication, however, she received no official recognition even when Irene was decorated for her work alongside her mother. When, in 1921, Marie was finally offered a Legion D’honneur, prompted by a high-profile visit to the USA where she met president Warren G. Harding, she turned it down.

While her discoveries were revolutionising science and medicine Curie, oblivious to the risks involved with handling radioactive material, had no idea her work was slowly killing her. Not only did she spend decades in laboratories working without protection, she would often sleep with radium in a jar next to her bed because the glow comforted her in the dark. In the years leading up to her death in 1934 her fingers became cracked and black, she suffered from tinnitus, was almost completely blind as a result of cataracts and endured fearsome headaches. Her research papers absorbed so much radiation that even today they remain sealed in lead containers and can only be viewed in strictly controlled conditions wearing full protective clothing. Today Curie’s conditions could have been identified and treated as a direct result of the work she did to create one of the most important scientific advances of the modern age. “Nothing in life is to be feared,” she said. “It is only to be understood.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37