Leading French journalist Marion Van Renterghem meets Tony Blair, one of Remain’s Don Quixotes suddenly realising their task might not be as futile as it first seemed.

From my side of the Channel, I initially saw you Remainers as some tribe of Don Quixotes, at war with windmills, assigning yourselves a quite impossible mission: to bring your compatriots back to wisdom.

Yet as time goes by, it seems that Quixotism might turn into something more achievable. The lies behind Leave are blowing up, the nation’s mood is changing, the move for a People’s Vote is growing. And you, Remainers, have become like little mosquitos, tormenting the government, creating a constant, inescapable noise which is giving ministers sleepless nights.

As a spectator, I am fascinated to witness such a spectacle: the officers who set the course are leaving the ship one after another (Farage has become a radio entertainer, David Davis and Boris Johnson have resigned, Jacob Rees-Mogg and others have cynically transferred their investments out of Brexitland); the captain herself, Theresa May, remains on the bridge – but hardly in control. And yet the ship carries on.

The UK today reminds me of the Fellini film E la nave va (And the Ship Sails On). In it, the ocean liner Gloria N sinks and the passengers evacuate by singing opera arias, after having triggered the First World War. As I watch, I’m amused. As a European, I’m bemused. And scared. Because your story is ours.

But there are mutineers on board the UK’s ship, and in recent months, I have been meeting with many of them: brilliant debaters emerging out of nowhere like Femi Oluwole; previously unknown voices like Gina Miller; older hands putting all their energy to shift opinion, like Nick Clegg, Andrew Adonis, Peter Mandelson… and Tony Blair.

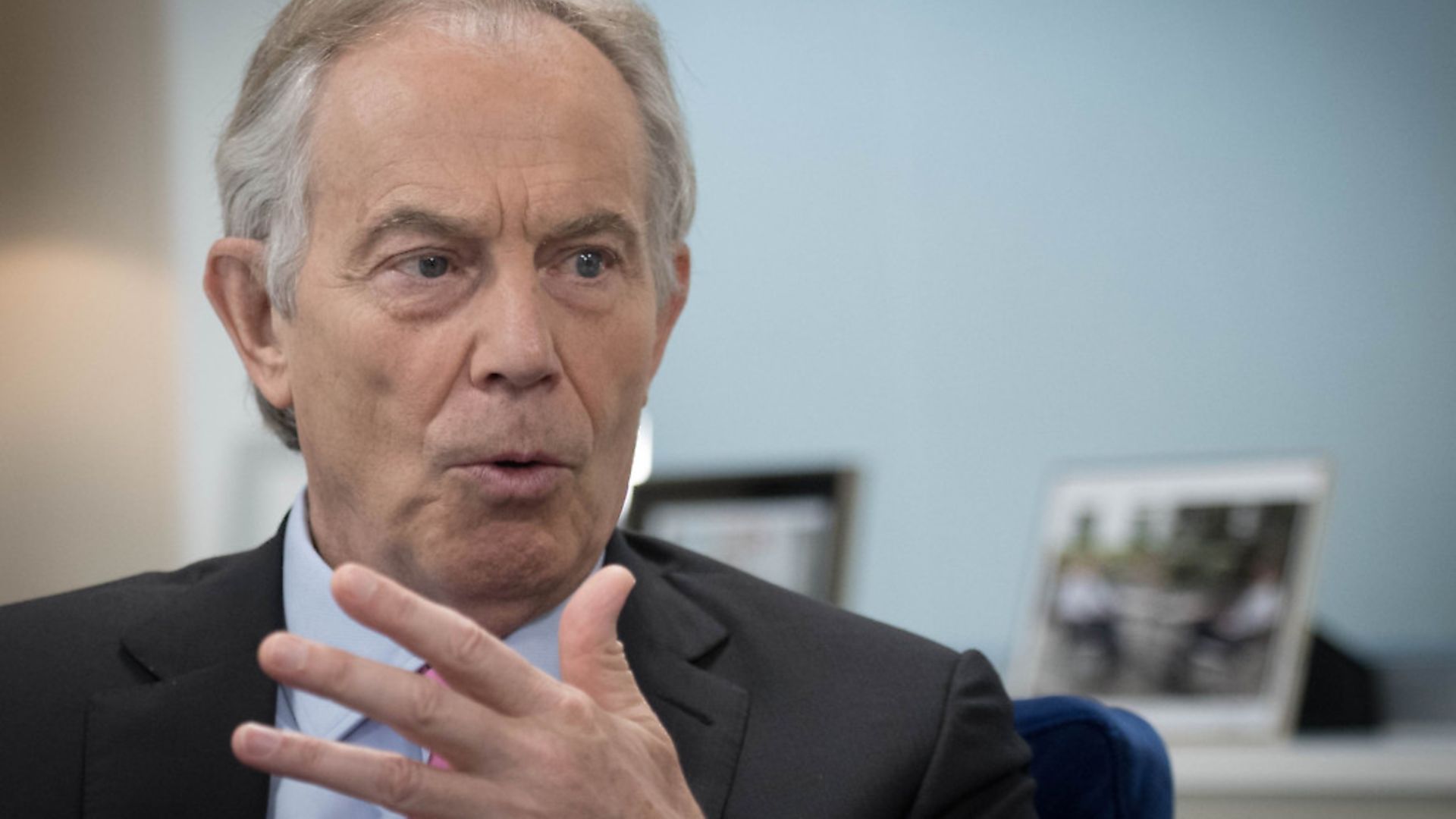

In Paris, Brussels and London, I’ve been meeting regularly with your former prime minister – the most intelligent and reformist politician you have had in recent times, and the man you hate the most.

At one meeting, he stares at me like a martian and dissolves into laughter when I tell him that Europe’s misfortune – Brexit – stemmed from the fact that Britain did not lose the Second World War. I insist: the arrogance of you British and your current teenage crisis over ‘independence’ results from the fact that you were able to stand up to Hitler. ‘You, the British, look down on Europe because it was defeated, while you weren’t,’ I tell him. ‘As a result, you live under the delusion that the EU isn’t of any use to you, except possibly to facilitate your business affairs.’

He stops laughing and admits: ‘The British tend to forget the importance of their European heritage. They wanted to join the Economic Community in 1973 only, and they didn’t understand that they should have been a founding member in 1951 or 1957. This would have changed everything.’

He adds: ‘My vision of Europe has always been political as much as economic. We signed the European Social Charter and I personally laid the foundations for a European defence policy in 2000. Europe must not be only a market, but a broader project that takes into account the social dimension of the market.’ The trouble is, even then, he was one of the only Britons to think so.

Years of criticism have given Blair the expression of a Hamlet haunted by some spectre. His hair has whitened, the forehead has darkened. Yet his courtesy and cheerfulness seem to have resisted all the blows.

Even in France, politicians of the left are careful not to mention his name publicly, even though some keep on having meetings with him and envy his exceptional career in power: elected three times for his visionary reforms in the NHS and education and for his humanitarian interventions in international crises.

When campaigning against the Conservative, Nicolas Sarkozy, in 2007, socialist Ségolène Royal was blamed by her own party for praising Blair’s policy. Sarkozy himself was more open about their friendship, and said recently that he and Blair might work on some projects together. Emmanuel Macron, when a candidate for the French presidency, said that he was not ashamed to be compared to Blair – he didn’t insist too much, however, knowing this statement would act like a scarecrow to his voters on the left.

Anglo Saxon politicians can’t easily provide a simple template for French ones, who traditionally tend to celebrate the role of the state in the economy. Blair will always be considered a man of the right by the French left – just as he has come to be seen on the British left, since Corbyn shifted it further to the extreme.

Then there is Iraq. His burden, the tragic mistake that has thrown him into hell. His deep motivation for following George W Bush in his Baghdad mission remains a mystery. Was it strategic loyalty to the Atlantic alliance, as he himself explained? Or a kind of a religious revelation? A journalist told me he was present for a telephone conversation in January 2001 in which Bill Clinton urged his friend Blair to be ‘as close to Bush’ as he had been to himself.

According to a YouGov poll earlier this year, only 17% of Britons have a favourable image of Blair. The most smiling of all prime ministers has learned to live with this hostility. ‘I can’t prevent people from hating me nor can I force them to listen to me,’ he says quietly. ‘But they can’t prevent me from speaking out what I believe in.’

One of the main reasons – apart from Iraq – why Blair irritates you British so much might be that, in one crucial respect, he is so different to you: he is viscerally European.

By European, I mean supporting a community of political, ethical and social values – not only a single market, for one’s own interest. In that sense, Blair is the first genuine European to have occupied Number 10 since Churchill, even if – paradoxically – he is blamed on my side of the Channel for being too British and not European enough. Wasn’t he the strongest supporter to the enlargement of the EU in 2004 and the man who favoured intra-European immigration, both of which have contributed to today’s populism?

‘The context was different,’ he answers. ‘In 2004, the economy was booming. If I had been in power for the last ten years, I would have hardened the rules on immigration. It remains desirable and necessary for the economy, but we must hear the anxiety it arouses and regulate it. As for enlargement, can you imagine the eastern countries left behind, with the emergence of Russian nationalism? They would have been more vulnerable, and so would we.’

He pauses, looks for words by looking up to the ceiling and concludes: ‘The irony is that the single market and the enlargement are British initiatives – Thatcher, then Major, then me. The Brexiters now blame Brussels for what Great Britain wanted and supported… They want to ‘take back control’, but I can’t remember one single law imposed by Brussels that I would have been forced to apply. They want a ‘global Britain’ whereas only the European Union can be global, facing the three economic giants – USA, China, India.’

A silence again, eyes to the ceiling, then: ‘There are two irreconcilable groups among the Brexiters – those who are scared of globalisation and those who are scared of a too socialist Europe. If Brexit takes place, this coalition will burst.’

He adds: ‘The government wants to believe that this is a negotiation with the EU, but it is not. Either we stay close to the EU, then we wonder why there would be any reason to leave, or we leave the EU, then we accept to lose the benefits of the single market. There is no alternative.’ The inevitable restoration of some sort of border between Northern Ireland and the Republic that Brexit will bring – an issue particularly pertinent for Blair, as an architect of the Good Friday Agreement – is, he says, a ‘metaphor of the impasse’.

The former prime minister was among the first to articulate calls for what is now called a People’s Vote. ‘We have the right to reconsider the issue once the deal between London and Brussels is known,’ he told me, back in November 17. ‘It would not be a second referendum, but a new one, given the situation itself is all new. Brexit as it now looks like has nothing to do with what people have voted for. Until March 29 2019, it is not too late.’ Back then, it was a fringe view. Not any more, if the polls are correct.

As a strong European myself, I couldn’t understand why you Remainers didn’t take the opportunity, at the last general election, to vote for one of the two only pro-European, UK parties you have: the Greens and the Liberal Democrats. Instead, you showed a Pavlovian link to the two-party system, and then blamed Jeremy Corbyn for his persistent silence on Brexit, despite his notorious, long-standing anti-European credentials.

Blair insists he voted Labour in June 2017 and pretends not to have given up hope that Labour will play the role of a centrist party – ‘but that looks increasingly unlikely,’ he admits. As we would say in France, by the time Labour comes back to the centre hens will have teeth.

So does a new, centrist party remain a possibility for the UK? ‘The paradox,’ Blair answers, ‘is that a majority of people would vote for a centrist policy – a strong market economy together with a liberal society, justice and mobility not for the few but for the many – while both the two main parties can only be taken over from outside the centre. That is why they both are disappointing and deceitful.’ What happened in France with Emmanuel Macron, who broke through with a new political party, En Marche, by blowing up the old ones, can hardly be replicated in the UK’s parliamentary system. But old French politicians thought the same regarding French politics. And all laughed at Macron when he launched his attempt. So perhaps, with Brexit, it should be worth a try in the UK.

The countdown is running in the UK, and across Europe, towards March 29, 2019. Whatever the outcome will be, the anger that caused Brexit remains. As in all European countries, British society is cut in half. In my meetings with politicians from different parts of Europe in recent months, I have never heard such uncertainty. In such uncertainty, as regards Brexit and the possibility of a second referendum, Blair can find some optimism – or pessimism, depending on how you look at it. ‘Everything is possible,’ he says

Marion Van Renterghem is a reporter-at-large and a writer. This article has been partly adapted from a piece published in Vanity Fair France online

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37