Netflix series Master of None has successfully negotiated a change of focus after its creator was caught up in a #MeToo scandal

The first two seasons of Master of None sound awful when described – “an actor bops about New York dating beautiful women and eating at nice restaurants” – and sometimes they are.

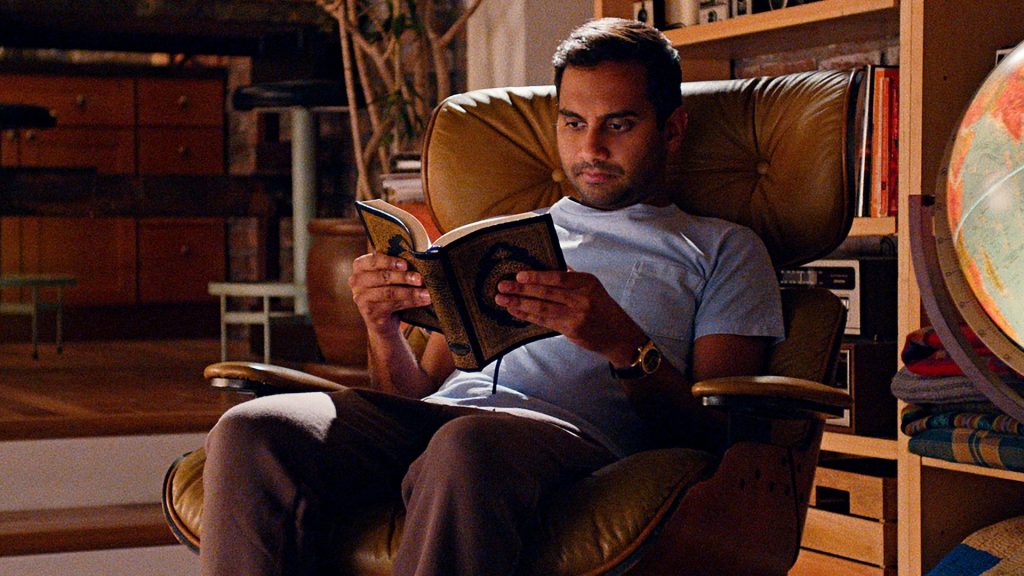

Aziz Ansari stars as Dev, a second-generation Indian immigrant who has grown up and lives in New York, and though he has his struggles they are mostly related to some basically interchangeable woman he is seeing.

Mostly he enjoys an above-averagely charmed life in which he hangs out with his core friend group – Denise (Lena Waithe), a gay Black woman who has been a close friend from earliest childhood, Brian (Kelvin Yu), a handsome and urbane fellow who is also a second-gen kid, and Arnold (Eric Wareheim) a benevolent bumbling giant of a man who delights in picking the petite Dev up into his great encompassing arms.

He sees these charming, intelligent, witty pals of his and eats at good restaurants and sends daft messages to girls in the hope of ensnaring one of them. He pines after a true love affair, but usually in an abstracted fashion, not in any genuinely painful way.

The saving grace is that Ansari is so cute and funny that you still love to watch him even when the show begins to plumb the depths of the metropolitan mundanity it is focused on a little too thoroughly.

That’s the problem sometimes with these inordinately blessed male auteur types who get to make shows and films about little more than their shopping lists. It’s so cliche, so annoying that their pitches can be so generic and broad and empty and still get commissioned, but at times it just works.

I really enjoyed the first two seasons of Master of None, despite its sometimes oppressive insistence on prioritising banality. It is in the end hard to feel much for Dev, even if you enjoy the show.

But much has changed in the intervening years. (The first series came out in 2015.) The world at large somehow became even worse. Covid meant that a show involving gliding around chi-chi pop-up supper clubs and parties could neither be filmed safely nor represent any kind of reality. And Ansari was accused of sexual misconduct by a writer for the now defunct Babe.net.

It was a strange addition to the #MeToo canon, arriving at a time when we as a culture were readdressing what we were willing to condemn or speak out about. I, like most people who care about both gender politics and also comedy, was confused.

The deeds he was accused of were bad but not criminal, and yet because of the time frame in which they were released they had the air of something career-ending. In retrospect the whole thing eventually led me to think about how I would feel about – and how I would come out of – a situation in which everyone I’ve ever slept with described in un-nuanced detail all of our sexual encounters. Would any of us come out of that clean? Would it inevitably contain some unflattering manipulative or pushy behaviour?

I wasn’t sure he would come back from it successfully, but I always hoped that he would. Season three of Master of None is a fine affirmation that he has and that he ought to have. Dev makes brief cameos but the focus of attention has been entirely recentred and instead follows Denise, now a successful novelist and married to Alicia (Naomi Ackie). They live in a gorgeous, isolated house in upstate New York where we see their marriage play out and unravel.

The series is subtitled “Moments In Love” which is a good indicator of the change of pace we are witness to. It’s a largely stationary rather than dynamic experience, by marked contrast to the previous seasons, and though this won’t be for everyone I found it moving, even mesmerising.

There is nothing more fascinating to me than what takes place in other people’s relationships out of view. Though this insight makes us privy to the darker sides of love, there are also ample ambient pleasures, brief windows of hysteria and giddiness.

As a long term happily single person myself, I rarely envy couples and recall only dimly what the benefits of mutual obligation are, so long have I been fixated on the drawbacks. But here there is a three second scene of the two women bent over double in the garden helpless with laughter which recalled something long buried in me. Oh yes, that’s why people do it, I thought.

I have no idea whether Ansari would have reframed the series regardless of the allegations made against him. It seems possible he would have, seeing as he told New York magazine “I’ve got to get married or have a kid or something. I don’t have anything else to say about being a young guy being single in New York,” as far back as 2017.

Some have regarded this shift in direction as some kind of apology for his sins. Although it is indeed a rare treat to see a major populist television show concentrate on black queer women, I would hate for the show to be seen as some kind of reparative medicine Ansari or the rest of us watching must take.

This is not a tokenistic effort at representation or an atonement. This is a seriously beautiful reflection on intimacy and on what happens after you get the thing you thought would fix your life – the book deal, the house, the wife. We’re lucky to have it.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37