Does what we know about its creators’ mental health overshadow the brilliance of The Goon Show?

Can the all-too-familiar concept of the sad clown spoil the enduring charms of one of British comedy’s enduring monuments?

It is a question worth asking this month, on the 70th anniversary of the first UK broadcast of radio comedy The Goon Show, as appreciation of the series has become increasingly clouded by subsequent disclosures about the real-life mental health problems of two of its stars, Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers.

The sufferings that Milligan and Sellers inflicted on themselves and others has been repeatedly recounted in feature films and documentaries, books, and articles. Can the BBC Home Service programme, which originally ran from 1951 to 1960, still inspire laughs amidst all the grim background info?

The documentary Ghost of Peter Sellers (2018) directed by Peter Medak, about the star’s sabotaging of a 1973 film shoot followed Geoffrey Rush’s frightening performance in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (2004).

Milligan’s own woes were recounted in the documentaries Spike Milligan: Love, Light And Peace (2014), The Unforgettable Spike Milligan (2010), and The Unseen Spike Milligan (2005).

Then there were the series of posthumously published books by Milligan, edited by his long-suffering agent Norma Farnes, as well as her Spike: An Intimate Memoir (2003). And the stage plays about his depression, from the acclaimed Ying Tong (2011) by Roy Smiles to the less well received, but certainly depressing, Surviving Spike (2008) by Richard Harris.

The cumulative weight of this documentation has made audiences ultra-aware of the damaged psyches of Sellers and Milligan. By contrast, the third Goon, Harry Secombe radiated Church of Wales piety, and his enduring marriage and placid personality provided infinitely less fodder for the gossip mills.

Just as Michael Bentine, another founding Goonfather, was infinitely more clubbable than his colleagues, even if tensions with Milligan led to an early departure from the show.

Both Milligan and Sellers had episodes of physical violence, but unlike Milligan’s repeated hospitalisations, Sellers cagily avoided psychiatric treatment.

Not only did Milligan accept electroshock therapy, he even sought counsel from the psychiatrist Sydney Gottlieb, who treated performers at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club, where Milligan played trumpet.

Gottlieb, who had ministered to concentration camp survivors, homeless alcoholics and drug addicts, apparently had a way with the fragile psyches of jazz musicians.

Possibly due to the counsel offered by Gottlieb, Milligan’s rapport with his children differed entirely from that of Sellers with his own offspring.

Sellers was given to banishing his children from the house after asking enraged King Lear-type questions about whether they loved their mother more than he; or if one of his performances was insufficiently adulated.

By comparison, Milligan doted on his offspring, telling them stories that developed into a series of books in verse and prose for young readers.

Where do these domestic details leave The Goon Show? An aural extravaganza playing on classic radio and movieland themes, it was essentially a musical phenomenon. In relentlessly paced routines, the abundant wordplay was like verbal melodies.

As Neddy Seagoon, Secombe’s high voice squeaked, as if in a permanent tone of outrage or amazement. Periodic interruptions came from explosive sound effects, since Milligan’s mind was permanently situated on a battlefield where he was fighting Adolf Hitler, and laughter when the performers were tickled by their own ridiculousness provided further sonic punctuation.

The surreal show’s catchphrases were endearing, like Sellers’ suave villain Hercules Grytpype-Thynne, who habitually substituted improbable objects for cigarettes or cigars, asking Secombe’s Neddie Seagoon: “Have a gorilla?” To which the reply was, “No thanks, I’ve just put one out.”

Or the uncanny, fluty-voiced Bluebottle, another Sellers role, exclaiming: “You rotten swine! You’ve deaded me!” Has the dizzying comedy itself been deaded by continuous revelations about the lives of the comedians who created it?

All three stars were musicians: Harry Secombe was a Welsh tenor, whereas Milligan was a jazz trumpeter and crooner in military ensembles during the war. For his part, Sellers was a jazz drummer who also performed in wartime shows, playing the ukulele and singing in George Formby imitations.

The frenzied Goonish sprees were interrupted by musical interludes from the singer Ray Ellington and the jazz harmonica player Max Geldray, much-needed respites from the full throttle comedy that preceded them.

According to Milligan, the show’s title was inspired by Alice the Goon, a character from E. C. Segar’s Popeye cartoon series. Alice the Goon was a giant guard for a vicious pirate who traumatised America’s children by her monstrous appearance, leading to calls for her ferocity to be toned down.

The UK Goons were never toned down, although the BBC Light Programme did title the trio’s first shows Crazy People with the subtitle The Junior Crazy Gang.

This was an attempt to strike a familiar tone with audiences by alluding to a more decorous comedy group of a previous era, The Crazy Gang. Moving from these venerable entertainers to the Goons was like leaping from the paintings of Gainsborough to Salvador Dalí.

For Milligan and his Goons, danger, fear, violence, and death were never far away. Yet apart from when he was in state of emotional collapse, Milligan generally channelled his violence constructively.

While Sellers appeared to be interested in the usual Hollywood pastimes of acquiring the latest starlet or fastest sportscar, Milligan, especially during regular times of unemployment, was a defender of noteworthy causes.

Starting in 1957, Milligan participated in the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC), a pacifist organisation that preceded the 1960 Committee of 100, a mass civil disobedience effort.

In both ventures, he marched alongside Bertrand Russell, Doris Lessing, and other intellectuals with a public vocation.

Milligan ardently fought for animal rights and architectural preservation and against smoking and domestic violence, without being offensively self-righteous, because of the eccentric violence with which he expressed his beliefs.

In 1971, an American conceptual artist announced plans for an installation at London’s Hayward Gallery consisting of a fish tank with catfish, lobsters, shrimp, and crabs which were to be electrocuted and later served to exhibition goers.

Disregarding the artist’s pious explanation that this was intended as a demonstration of an “ecosystem that can be harvested”, a furious Milligan appeared at the gallery during a private view and smashed the glass front doors with a hammer.

Milligan’s activism was equally eye-catching and effective in preserving old buildings. In the 1960s, when unsightly concrete lamp posts were installed in Constitution Hill, a road in Westminster, Milligan objected and the new atrocities were replaced with the original, more picturesque, gas lamps.

Wilton’s Music Hall in Whitechapel, the most majestic surviving Victorian music hall, was almost demolished in the 1960s, until Milligan fought for its preservation. He even made a short film, The Handsomest Hall in Town (1970), recreating a night at the Wilton’s of yore.

The same year, he supported the salvage of SS Great Britain, a former passenger steamship which had been scuttled in 1937. It was finally raised, repaired, and returned to the Bristol dry dock where it had been built. Likewise, he managed to help preserve HMS Warrior, now a feature of the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.

Ramblers through London’s Kensington Gardens may have noticed Elfin Oak, a sculpture made from the hollow trunk of an ancient oak tree, carved with figures of elves and animals. Originally designed in 1930, it was restored in 1996, with funds raised by Milligan, and one year later declared a Grade II listed structure.

So after Milligan unexpectedly survived the war where he endured shellshock and related trauma, his instinct was to brighten the corner where he found himself.

In January 1970, Milligan wrote with justifiable pride to his friend the poet Robert Graves: “Nothing can stop ‘progress,’ especially the destruction of old buildings, that is, nothing except Spike Milligan. I am a pretty old building myself.”

He went on to cite successful efforts made in Australia, where his mother had retired to Woy Woy, a coastal town in the Central Coast region of New South Wales.

There, Milligan would retreat for writing holidays; ever public-spirited, he supported the local theatre and orchestra, and campaigned in the 1970s to preserve Riley’s Island, an uninhabited nature reserve, from real estate development.

While Sellers turned out a ceaseless series of mostly bad movies as his film career boomed, Milligan, comparatively idle professionally, had time to preserve the former St. Luke’s Church in Woy Woy, the oldest timber church building in the City of Gosford, as well as a previously unrecorded Aborigine cave decorated by carvings and paintings of the extinct Dharug tribe.

Milligan also noted among his achievements in a semi-serious self-penned anticipatory obituary in the Sunday Correspondent in July 1990: “I found and saved the convict-cut stone cottage of major early Australian poet Henry Kendall.” The home of this 19th century author and naturalist is now a museum.

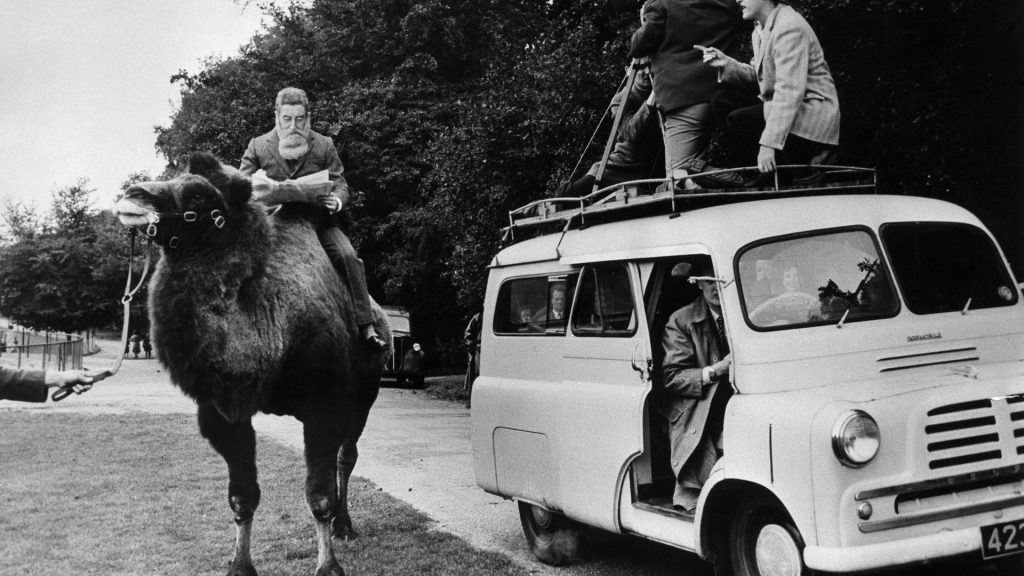

An Australian Broadcasting Corporation short film, Spike Milligan Takes a Young Look at Australia (1971), alternates shots of the wild-eyed protagonist in silly wigs and serious discussions of historical preservation and the natural world.

His characteristic lunar, mad-eyed stare explains why for some audiences, Ben Gunn, the crazed castaway in Treasure Island, was the ideal role for Milligan in annual productions at the Mermaid Theatre. Also unforgettable was his West End appearance in 1964’s Son of Oblomov, in which he basically improvised a new play nightly, based on a 19th century novel by the Russian author Ivan Goncharov.

Sellers was also a brilliant performer, from his cat-loving Dr Pratt in the cult comedy The Wrong Box (1966) to his note-perfect gardener Chance in Being There (1979). Yet in Sellers’s increasingly tiresome and predictable Inspector Clouseau films, the exaggerated French accent and umpteen pratfalls look dated today.

But the wild universe of The Goons can never become passé, any more than other great English predecessors in nonsense, from Edward Lear to Lewis Carroll. And Spike Milligan’s intense devotion to nature, beautiful architecture, and other fine things of this world ensure that future generations will appreciate his comedy, above and beyond the admittedly weighty record of his life’s travails.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37