MICHAEL WHITE discusses the week Theresa May gave way and Europe rejected the old politics.

I know it’s out of fashion to be fair to Tony Blair, even among people who should know better and do. But at least he won a few elections and managed to do some good before his government’s share of the vote started shrinking, down to 35.2% in 2005, so I recall. Jeremy Corbyn’s ‘constructive ambiguity’ over Brexit, itself a generous description, has now cost him another election battering without any doing-good interval.

Last Thursday Labour slipped further from the 40% it unexpectedly won in the 2017 general election. Heading south via those 35% (2018) and 28% (2019) local election ties with the Tories, it dropped to an ignominious 13.7% vote share as the leadership’s strategy fell noisily between Leave and Remain stools – much as predicted by all but the dwindling band of Corbyn’s True Believers. There is always a place for tactical duplicity and low cunning in politics, but their success depends on voters either not noticing or not caring. Ask Nigel (‘Betrayed’) Farage to explain, Jezza.

Unfair? Of course it is. For one thing this was a single issue protest vote as general elections are not. For another, the Conservatives did much worse. They plunged over Theresa May’s very own Brexit cliff to 9.9%, apparently the party’s worst result since its Rees-Mogg wing made a serious hash of the Great Reform crisis in 1832.

But politics is often unfair, a very rough old trade. The fact is that the parties which adopted a clear position on either side of the Brexit divide did well, the Remain coalition slightly better than the Farage insurgency. It was the fence-sitters and the divided who suffered a well-deserved defeat, one in which woad-wearing tribalists like Michael Heseltine and New European editor-at-large Alastair Campbell defected to Vince Cable’s tribe for the first time. Lib Dems beat the Tories in Maidenhead and Labour in Islington. Labour came third even in pro-Brexit Wales and lost Momentum Millennials in London. Yet the very people who seem to duck expelling anti-Semitic mates rush to kick out Campbell.

Barely had the scale of the Con-Lab disaster begun to register on BBC1’s election touch-screen at 10.05pm on Sunday night than Emily Thornberry clambered off her Islington neighbour’s rickety fence and called time on the policy. Things must change. John McDonnell’s finger-drumming frustration with his indecisive old pal – Happy 70th, Jeremy – has been obvious for many months, so he was not far behind her in demanding “a public vote” to resolve the stalemate. An election or a referendum, John? The latter looks more likely since neither mainstream party – two parties which shared more than 82% of the vote in 2017 – would sensibly risk such a roll of the dice that calling Farage’s cocky bluff would entail.

In a letter dictated to him on Monday night, lethargic Corbyn shuffled closer to “a general election or a public vote”. But not today. Seumas and Len (“no panic”) McCluskey have held their red line: no formal commitment to a referendum or Remain before the annual conference. What’s the rush, eh!

Last week the big two parties were forced to consult the electorate to comply with EU laws to which their own failures still bind them. Voters were decidedly unimpressed. Brexit must surely be resolved one way or another before they dare trouble them again or the system is at risk. But how to get there? How to get anywhere? Theresa May’s tearful resignation statement was heart-rending or pathetically delusional, depending on your point of view in deeply-polarised Britain.

But, as Steve Richards wrote in his even-handed political obituary of the outgoing PM in last week’s New European, the degree of severity with which posterity regards her premiership will be shaped by whatever happens next. Watching her finally admitting defeat in the Downing St sunshine on Friday morning, I thought of Louis XV’s premonition of the guillotine. “Apres moi, le déluge.”

In Das Kapital, Karl Marx took that to mean that the French king didn’t care what happened to his successors, any more than the selfish capitalist class cares about its workers, a thought with some contemporary resonance. But the Tory deluge, which urgently confronts us all this unhappy summer, is not so much a flood as a second-rate shower of candidates for May’s job.

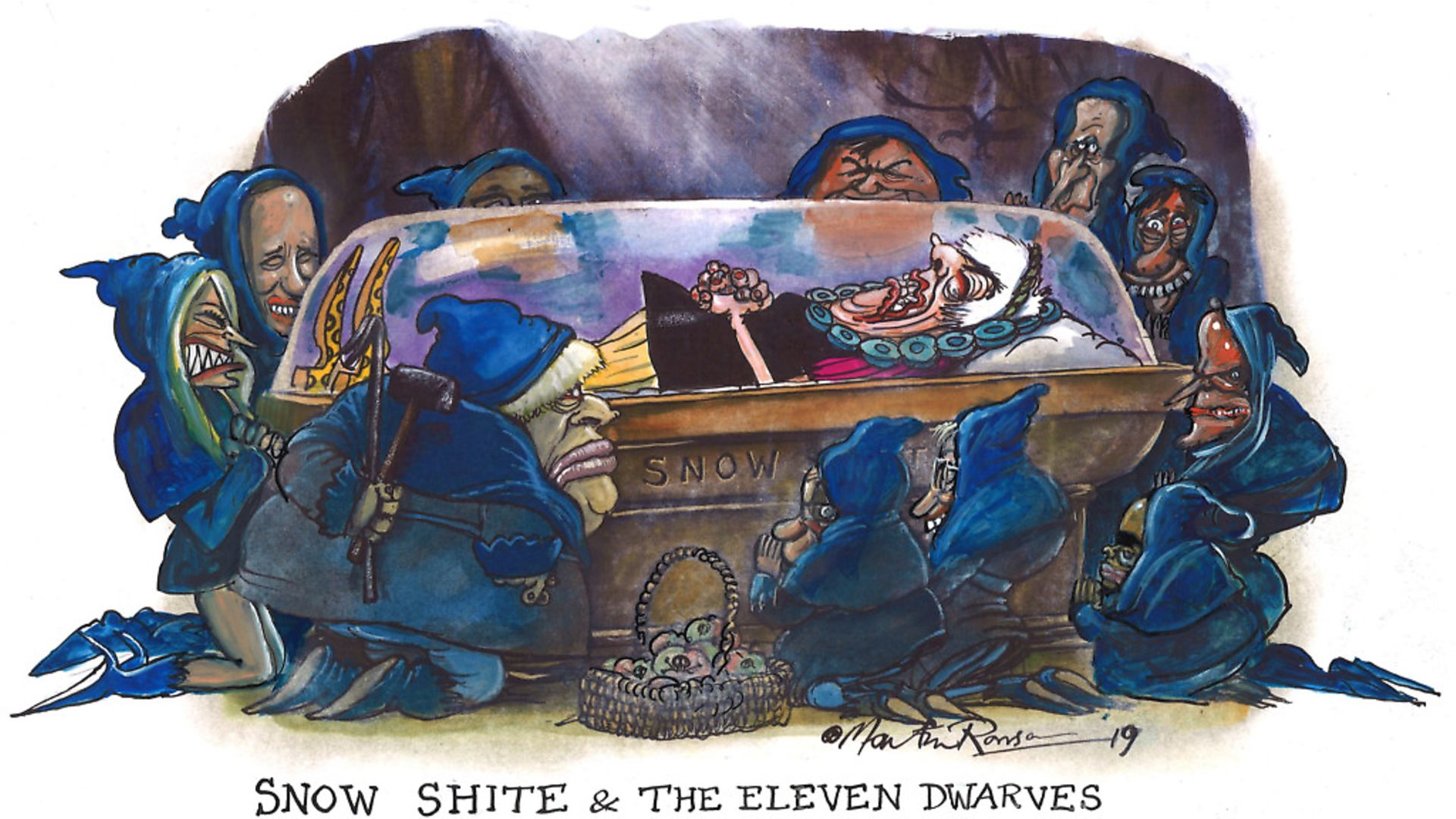

The trivial vanity of their ambition, the shallowness of most of their calculations, is measured by the sheer number of impudent wannabe prime ministers. How dare they insult us in this way when few of them would have made it into a Thatcher or even a Major cabinet? How dare they offer economically illiterate tax cuts and “my Brexit’s harder than your Brexit” taunts when the stalemate requires political creativity of the highest order to bind up the country’s wounds? No wonder Bumptious Bercow wants to stay on as Speaker to thwart their folly.

Let’s park the grisly blue parade of no-deal McVeys, Steve Bakers and Sir Graham Whos, lest we repeat their own self-absorbed mistake. Did you notice that none of these champions of economic sovereignty has made a serious response to the existential crisis at British Steel, which would once have dominated the headlines? I do not include Tory MEP, Desperate Dan Hannan, who survived the Faragiste massacre in the south east region but airily declared that we don’t need a steel industry, albeit only after the ballot boxes were safely closed. Not much sovereignty there, eh, Dan. Steel workers in Vote Leave Scunthorpe deserves better. So does the climate change challenge, law and order, health spending and much else.

Last week’s European elections (turnout up from 42.6% to 50.9%, UK 37%) were not primarily about us and certainly not about Brexit, of which our 27 EU still-partners are heartily sick. It was about the future of the continent’s great 63-year-old project, at a turning point for the wider post-war order of 1945 when nationalism is on the march again and a new Cold War looms across the Pacific.

Unlike the last one, Asia is the central battlefield, not Europe, which risks being marginalised and impoverished – as it was for most of the Middle Ages. A Chinese maglev train hit 370 mph on an air cushion the other day. Despite Silicon Valley’s prowess, the Yanks have no high speed trains. Wake up and smell the coffee.

How did Europe square up to the challenge to its purpose and fragile cohesion from insurgent nationalists and populists? Not well, though it could have been worse, as Emmanuel Macron said after his En Marche party was beaten (22.4%) by whatever Marine le Pen calls the family’s National Front franchise these days (23.3%).

Mainstream socialists did badly everywhere except in Spain and the Netherlands. So did the traditional conservatives, nowhere more conspicuously than in Germany, where chancellor Merkel’s CDU/CSU alliance dropped to 28.9% as the right-wing populists of Alternative for Germany (AfD) advanced to 11% and the co-governing SPD fell to 16%.

In Italy, publicity-savvy Trump fan, Matteo Salvini doubled Lega’s poll share to 34% (tripled it in the excluded south) while the Five Star Movement, lacklustre partners in Rome’s Mogg-Corbyn populist coalition, went the other way: down from 32% in last year’s general election to 17% last weekend.

Can we take comfort from the widespread surge in Green votes? Some do. In Germany they came second on 21%, helped by that 26-year-old YouTube star called Rezo, whose 55-minute video assault on the coalition partners’ policies was seen by 12 million voters.

Young voters were energised for Europe, not least by Brexit, I’m told. Green MEPs, including seven from Britain – for now – will have 69 seats at the new Strasbourg parliament, up 19. The centrist/liberal parties did even better, up 42 to 109, chiefly thanks to Macron’s French realignment and (up from one to 15 MEPs) Sir Vince’s resurgent Lib Dems. The Danish anti-migrant People’s Party got hammered, as of course did UKIP, whose leader, Gerard Batten, lost his seat. But Austria’s populist coalition held its vote share 24 hours before an internal scandal destroyed it.

In search of silver linings, Guardian columnist and former Le Monde editor, Natalie Nougayrede, saw the result as a rebuff to Trump’s attacks and the predicted nativist surge, a success for the pluralist politics of cooperation and the need to prioritise environmental action. So did Liberation in Paris, which splashed on the “Rise of the Greens” and “Europe is Resisting”. Other commentators were not so sanguine and nor am I.

With honourable exceptions, notably former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer and Baden-Wurttemberg’s veteran PM, Winfried Kretschmann, Greens are infrequently well-rounded executive politicians – realos, as distinct from the single-issue fundi kind. Ditto Nigel Farage, who offers glib soundbites but flees responsibility.

I sense complacency in the mainstream verdict that the far right’s result was ‘a consolidation, not a surge’. The populists may be a byword for infighting and treachery, but Salvini may be made of tougher stuff. He seems determined to mould the Le Pens, Faragistas and Hungarian Orbanites into an effective bloc of around 150 in the 751-seat parliament where – the election’s most significant outcome – the established centre left and right blocs which ran the place finally lost their majority.

That could matter almost immediately because the EU’s fixers went into instant conclave mid-week to sort out the big jobs now coming vacant, notably Jean-Claude Juncker’s presidency of the Commission and – arguably much more important – the presidency of the European Central Bank (ECB) after the creative Mario Draghi steps down. And remember, the Salvini bloc, no longer talking of their own Brexits, is committed instead to “disintegration” policies in Strasbourg and when blocking minorities emerge in the Council of Ministers.

The Germans want their CDU MEP, competent but colourless Manfred Weber, in Juncker’s post, using the spitzenkandidat rules that give it to the lead party’s candidate. But the European People’s Party (EPP) bloc, which David Cameron so rashly left, has only 180 seats (down 37) and the socialists just 146, down 41. They are short of a majority and need the Liberals or Greens. Macron is anti-Weber. Does it matter to us? Yes, because the Germans may demand the ECB job as a consolation prize, and German financiers are more cautious about everything than Draghi and his quantitative easing policy. If they tighten the monetary screws on top of Germany’s tight-trousered fiscal obsessions, then we all suffer – in or out.

How do the new alignments translate in terms of future negotiations on Brexit, our departure (on October 31?) and future trading relationship? Instant wisdom says it will make things harder for whoever is unlucky enough to win on a promise they can do better than May’s aborted deal. The impulse of the federalist priesthood in Brussels to punish us further for our sins will be intensified by the evidence from all over the EU that nationalist and populist reaction is not confined to Britain.

That the populist revolt is economic, political and cultural is something the priesthood will again be keen to dismiss, by doubling down on the easier bits of the project – like being mean to us.

Against this, the EU runs a hearty trade surplus with the rest of the world, not to mention with the UK, which is vulnerable to China’s retrenchment and – like British Steel – to Chinese dumping, as well as to Donald Trump’s trade wars on many fronts.

As Angela Merkel’s authority, and her coalition’s cohesion, weakens those export-minded car makers may finally protest, as Iain Duncan Smith has long instructed them to do. More rigid or more flexible? Perhaps a little of both. That may depend on who they are up against. Just as Team Corbyn is being pushed towards a Remain/referendum stance, so most Tory wannabes are being pulled towards the Farage magnet of a hard Brexit, not just as an implausible negotiating ploy, but as choice. Boris Johnson (bear with me while I call him Doris for the campaign’s duration) did it first and was slapped down by chancellor Hammond. Rory Stewart had the guts to say he wouldn’t serve under Doris who, so we learned this week, got stuck on that zip wire because he also lied about his weight. On Today the emollient Hunt said he’d include DUP representatives, the Moggsters and figures from Scotland and Wales in a new team to renegotiate terms in Brussels, but not “insincere” Labour or Farage’s “we demand a place” Brexit party. Hmmm. Time is on their side, not ours. There won’t actually be a new commission to talk to until November.

But tone will also matter: if we threaten the 27 they will threaten us back, the foreign secretary warns, amid howls of “no compromise” from one side and claims from moderate Tories that May may have signed a ‘no re-opening the Withdrawal Agreement’ clause before falling on her stiletto heel. It is not a great place to be, is it? Stewart may indeed be the ‘Kill Doris’ candidate, but I fear only Down Trousers Johnson himself can do that now.

Right-wing Tory MPs and activists, who behaved so stupidly over reform in 1832, are having a periodic nervous breakdown. They had one over Corn Law reform in 1846, later over Irish Home Rule and ‘imperial preference’ trade rules, over Suez in 1956 and now Brexit. It should be cue for a Labour government. But that’s another problem. Farage to prop up no-deal Doris? Or accidentally to install no-decisions Jezza? Now there’s an Italian thought.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37