MICHAEL WHITE on whether a tapestry is all we get from Le President.

When Emmanuel Macron made his grandiose offer to lend Britain the Bayeaux Tapestry during his Sandhurst summit with Theresa May, one wag suggested how we might best reciprocate. Why not send Jacob Rees-Mogg to France as an exquisitely crafted fragment of our ancient national fabric and the nostalgia it evokes?

Even though the tapestry’s splendid purpose-built museum in Normandy is due for an upgrade (so they need somewhere temporary to park it), I suspect the trip will never take place because the 11th century graphic novel will prove too fragile to move very far. If it does, I favour lending the Rosetta Stone, discovered by a Napoleonic Frenchman, but part of Nelson’s Egyptian swag after the Battle of the Nile. It would be a more subtle tit-for-tat than Portsmouth’s invasion tapestry, the one which celebrates (Geddit?) D-Day 1944.

But hats off to Macron for an imaginative use of soft power, more rarely seen now than in days when emperors sent each other elephants, eunuchs or their rivals’ heads. Remember how the Boy Wonder (40) gave China’s Mr Xi a thoroughbred horse, a nice touch in a country which reveres them. When did we last have such a deft national leader?

Good question, Mike, but let’s not go there. Things have gone well so far for Macron, better than I feared, and he seemed quite constructive in his dealings with Theresa May – firm, at times regretful about Brexit, but also positive about forging a new trade relationship and sustaining old ones on defence and security. An extra £44 million to secure the Channel Tunnel’s fence at Calais sounds like a bargain. Even Mogg of Bayeaux could see that.

Contrast that with Boris Johnson’s summit bumbling about building a Channel Bridge (‘cheaper to move France closer,’ so experts told the Times). Not to mention his clumsy pre-cabinet briefing about finding an extra £5 billion a year for the NHS to get him off his Brexit battlebus (‘£350 million a week’) hook.

Everyone can see that May and Phil Hammond are going to have to stump up for health and social care, so this was crowd-pleasing attention-seeking on a Faragiste scale. Hammond dumped on him and Boris bottled it. Stick to what’s left of the day job, Boris!

We’ll come back to Macron, Brexit and the steady drip of manic briefings and predictions (it’s going to be awful or terrific) about what happens next. Goldman Sachs alumnus, Lord Jim O’Neill, was the latest star witness. Depending on which paper you read, Jim thinks the UK economy is doing better than Remain feared or not quite as badly as he expected.

You would not know it from its low position on the BBC’s news bulletins – way below trouser-dropping drama inside UKIP – Germany is surely the important European story this week. For want of better alternatives, Angela Merkel and her reluctant bridegroom, the SPD’s Martin Schulz, are edging back towards another grand coalition in the Bundestag. Church bells rang across the EU as the news spread, Jean-Claude Juncker probably treated himself to a small bottle of Leffe with his breakfast croissant. Europe’s anchor-regime had called off its divorce proceedings.

Well, has it? And should it? And how long will it all last? In the week when assorted bigwigs, pop stars and pimps (why do we never read about the pimps?) are gathered at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos it is incumbent on us all to feel optimistic. That’s what the bigwigs usually try to do while guessing each other’s fortunes in the snow. But I’m hard to persuade about Germany.

It’s hard not to look at the ruling CDU/Bavarian CSU coalition with the SPD and agree that it has harmed all three at the polls. It is hard not to note that the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) will become the main Bundestag opposition if the SPD’s 443,000 members eventually back the deal which Sunday night’s special conference vote narrowly agreed to explore.

This at a time when the nationalist government in prospering Poland – set to become the EU’s fifth largest economy and a major player after Brexit – is aligning with its smaller neighbours, Hungary, the Czechs and Slovaks, plus the new right-wing coalition in Austria, to resist Brussels on migrant quotas and much else.

Poland’s ex-PM turned Euro-statesman, Donald Tusk, even warns that Poland might do a Brexit of its own. No, I don’t believe it either, but Macron did concede during his London trip that French voters might have voted to leave if they’d been granted a referendum of their own.

We know that Turkey is edging further away from the gravitational pull of Nato and the EU with this week’s invasion of Kurdish-held enclaves of Syria. Thank goodness (irony alert) that far-sighted statesmen in Moscow and Washington will calm things down in the region.

The Italian economy is finally picking up – so it should as the wider world economy booms – but Italy’s looming election could revive ex-PM Matteo Renzi’s career as the new Macron (he used to be the new Blair) or lapse back into Five Star Berlusconi populism. Spain, the Brexit EU’s No.4 economy, is gripped by its secession crisis, where breakaway Catalans have just reselected the runaway, Carles Puigdemont, for leader.

So a lot rides either on the dwindling authority of Chancellor Merkel to keep the EU show on the road. If she falters, it rides on the largely untested Chinese horse-trader turned Norman carpet dealer in the Élysée. Merkel has been preoccupied for months by domestic politics. She didn’t do much for David Cameron’s referendum campaign when she had more power – and should already have been sensitised to the migrant issue which has since damaged her. Theresa May can look even less confidently towards Berlin for help.

So when the diminutive Kevin ‘Baby Face’ Kuhnert, 28-year-old leader of the SPD’s youth wing (Jusos), attacked his party leadership – yet again – at the weekend he made some telling points. ‘We cannot go into another election campaign where people tell us in the street ‘I can’t see any difference between you and the CDU’,’ Kuhnert warned. Of course, he’s right. As the liberal FDP and our own Lib Dems could confirm, voters don’t thank you for being a coalition’s junior partner, a mere ‘corrective mechanism’.

It might have been different if Schulz, bearded ex-president of the European Parliament, had brought home much SPD bacon from his negotiations with Team Merkel. Actually, he did. The grand coalition’s addiction to fiscal austerity – at home as well as in Athens – is about to be drastically weakened, as money is spent on everything from schools and pensions, childcare and housing, defence and public transport.

Germany’s entire budget surplus of 46 billion euros is going to be used to sweeten the coalition deal and make SPD voters feel better at the expense of CDU ones. That must be good news for growth in the Eurozone – Britain too? – where the size of German surpluses and the lack of German consumer demand has been a sore point for years.

But is it wise to hike spending in a boom when Germany is already growing at 2.2% but its population is ageing fast? Trump’s America is relaxing its fiscal girdle too, as the US economy surges. They may all be short of levers to pull which they had in 2008 if the boom bursts. They’ve mostly been pulled.

We’d love to have some of Germany’s surplus problems here. But we do have many of them, including a Labour party which thrives in opposition while ducking tough choices. The German left’s argument, that it can only rebuild in opposition, rests in part on the perceived success of Jeremy Corbyn in a very different Britain. If only.

Voters everywhere tend to take extra spending for granted until their own taxes go up. What Schulz failed to deliver on was his party’s flagship proposal during September’s failed election: to equalise access to Germany’s excellent but hybrid health care system for those with either private or publicly-funded insurance.

It’s a very sore point, the faster queue problem familiar to Brits but more so. The CDU saw the SPD plan as a centralising step towards an NHS, which few Germans seem to want. They conceded only higher insurance charges for employers. The CDU also resisted the SPD’s more liberal line on migrant caps while proving more flexible on lacklustre Schulz’s pan-Europeanism.

Over 12 years in power the pragmatic Merkel has colonised many centre-left positions, an echo of the Third Way politics of the Clinton-Blair ascendancy.

But, as we all now know, centrist technocracy which fails to address rising inequality (it still rising, whatever they claim), pushes frustrated voters towards those fringe populist parties. They are the ones with good slogans but few real answers. Donald Trump, scheduled to harangue the Davos crowd on the same day as Labour’s John McDonnell this week, is the populist poster boy, though President Putin has more photogenic biceps.

Little wonder that dull Schulz prevailed at Sunday’s Bonn conference by a slender 362 of the 642 votes available, a 56:44% majority which Alex Salmond would call virtually a defeat. CDU/CSU leaders reject as ‘catastrophic’ the minority government option or fresh elections that no one wants. SPD activists resent being captured by patriotic appeals.

Yet most commentators assume that the same activists (their party down to 18.5% in polls while the AfD consolidates its 12.5%) will bite the ‘GroKo’ bullet when they vote next month. ‘Europe and the world is watching you,’ Sunday’s delegates were flatteringly told. But none of us should sensibly place large bets in these volatile times when even introspective national agendas can be disrupted by external shocks. What price North and South Korean skiers colliding on the slopes during the Winter Olympics next month?

If this fragile GroKo (with just 56% of the parliamentary seats, compared with 80% last time, not actually such a grand coalition now) is endorsed and comes to pass, the implications for Europe may prove significant. Smart or not, Schulz got a commitment to EU integration that went beyond the clichés deployed in their 2013 coalition deal and way beyond what President Macron has been proposing. Germany would support – and help fund – a larger EU budget, create a Eurozone budget to sustain social convergence and structural reform.

It would be supra-national, not inter-governmental, not what Merkel’s CSU partners or her old finance minister, Wolfgang Schauble (now Bundestag president) like at all. Obviously most Brits, including many Remainers, are wary of continental grandiosity. Some saw Macron’s visit to Sandhurst as a Napoleonic fist in a Gallic schemer’s velvet glove. And how keen are those SPD activists on costly integration? Or the multi-party Dutch, let alone the wider Eurozone 19? Most face an insurgent populist backlash.

Will it happen anyway? After all, Merkel originally committed to reaching a deal over the Macron plan by March. Yet she may not even have a government by March. Her time is ending. Is Macron able to take the lead, as he would clearly wish? At 40 to her 63, he is both less experienced in every sense, a fast-track banker who got lucky, but also less cautious, an egotist at home with the Davos posse (he staged his own mini-Davos to make the point).

By way of contrast we can be pretty sure Brexit is going to happen. It remains to be seen whether German weakness and French ambition make it easier or more difficult to strike a deal that works and saves face for both sides despite mutual posturing. We glimpsed how the endgame will work when May cut her divorce terms agreement in December. So did a distraught Nigel Farage.

In sessions with invited British business leaders at the Élysée (I have heard a vivid account of one) Macron, speaking at length in excellent English while serving his own lunch, makes no secret of his wish to steal some City pie for Paris’s La Defense financial quarter. ‘France is back,’ he tells them, pointing to his labour and pension market reforms last autumn after 40 years of stalling. Next year may be harder, as enthusiasm for his En Marche coalition, broad but shallow, falters.

As fretful City types are saying, they would sleep better if DExEU delivered the position paper on its trade goals for financial services, the one promised last autumn. But French and German realists know that, however much of a hit the City takes, it will remain the indispensable financial hub of Europe.

ECB officials are warning against the perils of a hard Brexit, echoing the Bank of England’s Mark Carney, another Davos grandee. Macron’s more accommodating remarks during his flying UK visit fit into that pragmatic framework. Just as May’s ‘red lines’ on EU court jurisdiction are turning pink, so the EU 27’s core commitment to single market integrity can accommodate anomalies if it has to.

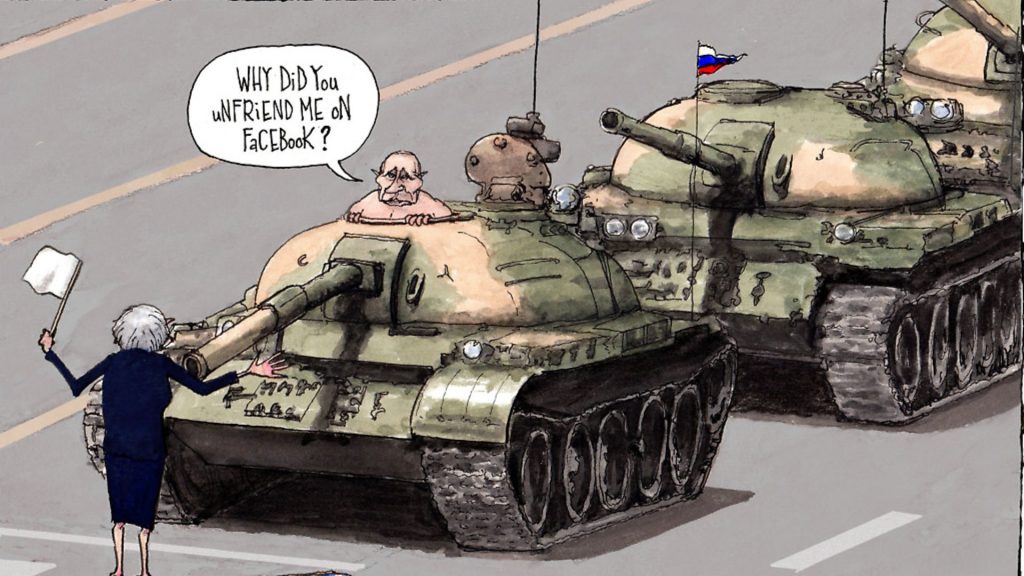

If the City’s wholesale money market matters to the Eurozone, so does Britain’s defence and intelligence contributions in the age of Trump and Putin, when Merkel may soon be gone and Nato is feeling centrifugal pressure, fomented by Russian adventurism – as fundraising UK defence chiefs briefed at the weekend.

Buried away in the small print of Carillion’s collapse is another apposite reminder of how inter-connected we all are. Big German banks are likely to be among the failed construction firms investors and will take a hit in the liquidation process.

With their lax regulation, Germany’s public sector regional (landesbank) banks, so admired by Labour policymakers in search of a big idea, will be in that category too. ‘Dumb German money’ is a phrase not unknown on Wall St. ‘Stupid Germans,’ as Michael Lewis put it in The Big Short, his eye-opening book on the bankers’ crash. They’d buy anything. It’s not just dumb Brits.

In August 1914 City bigwigs (no Davos then) had to be summoned to the Bank of England and told that it couldn’t be business as usual with Germany now we were at war. By 1918, Germany’s exclusion from global funds helped her defeat. One hundred years later we should know by now that we need each other.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37