MICHAEL WHITE on more infighting at home and abroad as leaders wobble but won’t fall down, just yet.

Do you feel relieved, or ever so slightly disappointed, when you open the morning paper or switch on the radio to learn that nothing sensational has happened anywhere overnight? Since the headline-hungry resurgence of authoritarian and nationalist populism, world affairs have become such a drama that I confess to feeling a little of both. As in ‘What do you mean, there hasn’t even been a deranged tweet from Trump?’

The deliberate elevation of drama over substance also makes it harder to sift what is serious from the merely sensational. My hunch is that Donald Trump’s decision to have a one-to-one session with wily Vladimir Putin at their Helsinki summit on July 16 is potentially very serious for Trump’s self-styled allies in NATO and the EU, if they’re still allies by the time he gets to Finland.

Angela Merkel’s stand-off with her Bavarian CSU coalition partners over immigration also has the potential to make life harder for the rest of us. The German chancellor’s paper-thin deal with the EU27 at last weekend’s Brussels summit (‘Brexit, what Brexit?’) seems to have persuaded her interior minister, Horst Seehofer, to withdraw his latest resignation threat.

But, as tricky regional elections loom in October, the Bavarian David (‘I may resign/not’) Davis is under pressure from both the insurgent AfD and ambitious right-wingers in his own party.

So model train buff Seehofer, 69 this week, could tie Merkel and himself to the track before Christmas, certainly before Brexit, in order that they perish together. There is no love lost between Seehofer and ‘Mutti’. The lofty Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung also accuses her of betraying constitutional conservatism.

The faces of her successors are unlikely to be friendly ones.

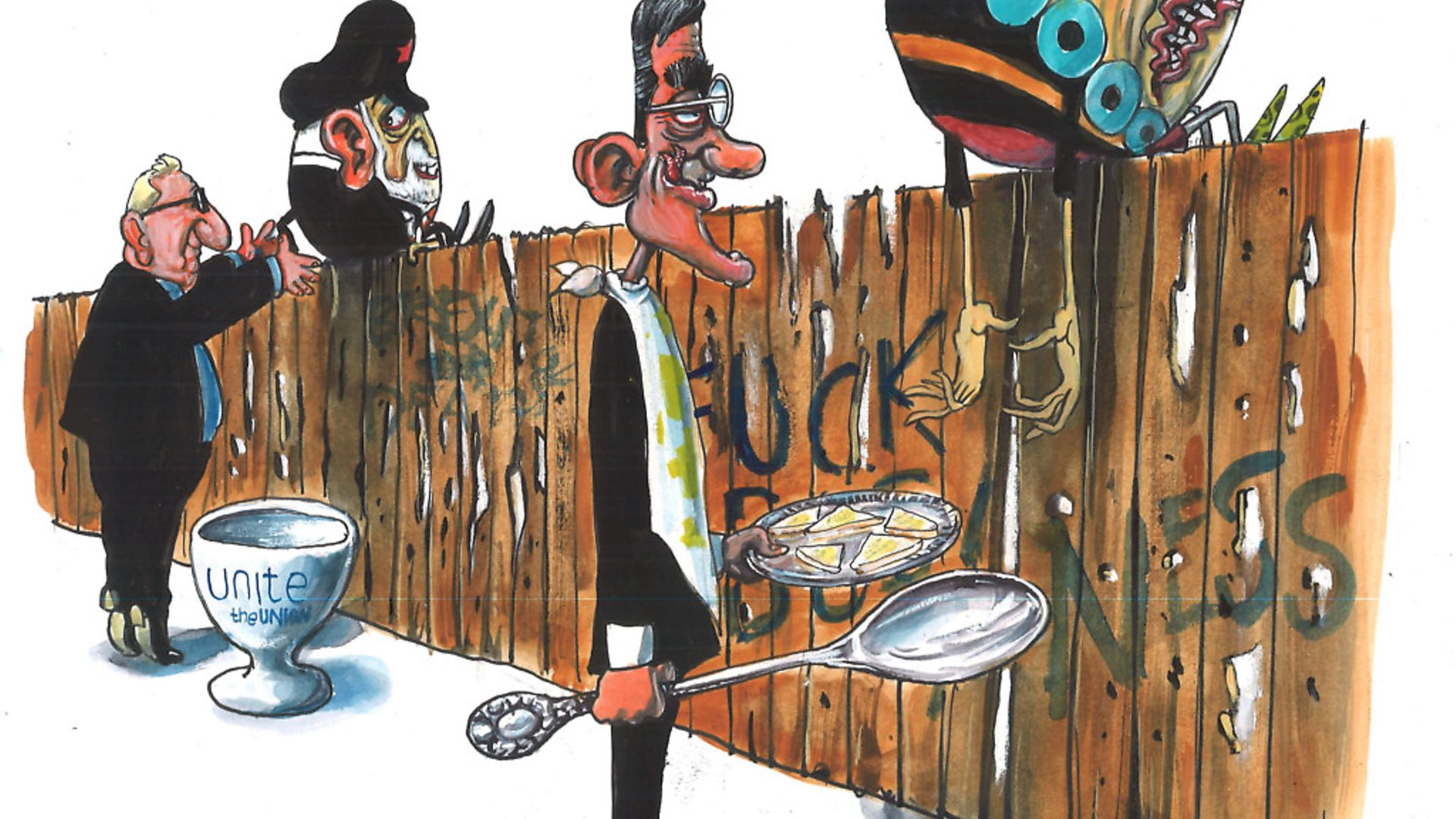

Which leads us gently towards our domestic drama where the merely sensational usually outweighs the serious. Will the combined efforts of younger, pro-European Momentum activists and the muscular influence of the Unite union – in conference this week – finally push Jeremy Corbyn off the fence his minders have erected and flatteringly labelled ‘constructive ambiguity’? Don’t get your hopes up. Labour’s lazy loyalist line is ‘we prefer a general election’.

They won’t get one.

Meanwhile Jez has this week acquired a new burden of expectation: Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, 64 and an avowed Corbyn ally, has been elected president of Mexico at the third attempt. The challenges ‘Amlo’ faces in his stunning-but-ravaged country make even Brexit look quite manageable – or would do if only the Tory party would behave like the natural party of government it once routinely claimed to be.

The immediate test is Team May’s latest version of a post-Brexit trading relationship with the EU, one that squares both Brussels, the Irish border question and a Conservative party, swathes of which are in betrayal mode. Floating a formula on Monday, but not revealing its crucial details until the promised cabinet away-day at Chequers on Friday, does not sound like smart party management to me. As with next week’s much-delayed Brexit white paper we would be wise to prepare for disappointment and the familiar sound of cans kicked down roads.

By way of preliminary skirmishing (unusually hot summer evenings on the Commons terrace cannot help) Tory MPs line up to threaten Theresa May over Brexit. Up to 20 of them reportedly look in the mirror and detect a future prime minister there. If cutting edge bio-science could extract the DNA of their individual best qualities and glue together one half-credible candidate from the 20 it would be some small comfort.

I had barely recovered from the genuine astonishment I felt on hearing that Jacob Rees-Mogg had called Boris Johnson a ‘terrific’ foreign secretary, a claim which is self-evidently false, before North East Somerset’s faux toff popped up in Monday’s Telegraph. He did so to warn May against the fate of Sir Robert Peel, the Tory PM who reneged on a manifesto pledge and split his party over Corn Law repeal in 1846.

Actually, I find the idea of Mogg as May’s stalker – think Jack Nicholson and his axe in The Shining – an overly flattering comparison, not least because JRM usually waves a rubber axe. Last week we learned that Cayman-based, Somerset Capital Management (SCM), of which he remains a partner, has taken the Brexit precaution of opening an office in Dublin. This week we learned that friends of O’Mogg have taken the precaution of sounding out PR firms to boost his leadership hopes. Very Michael Portillo (and we know what happened to him).

But any mention of Peel, the reforming Home Secretary who invented policemen (hence ‘Bobbies’), is OK here. In a more perfect world we should hear more about that earnest Victorian statesman, the Ted Heath of his day, than we do about Danny ‘Twat’ Dyer or indeed about O’Mogg, after whom no useful innovation will ever be called ‘Jakes’.

But O’Mogg’s reference to 1846 was an eye-opening moment for me. His article’s bullying tone drew reprimands for ‘impertinence’ from Alistair Burt and Alan Duncan, Boris’s ministerial deputies at the FCO and both solid citizens. Quite right too. Boris the Terrific was forced to intervene to defend O’Mogg. What fun it must be to work in the Foreign Office these days.

With No.10 running Brexit and foreigners laughing at the foreign secretary, there can be little to do but throw those famous Boris bog rolls across the office.

Impertinence apart, Rees-Mogg’s string of glib historical comparisons – our ‘Danegeld’ payments to the EU is both tired and ignorant – must also have disappointed those who expect more from a man with a 2.1 in History from Oxford. Had standards already slipped so much by 1991? By way of contrast, in 1808 young Peel became the first Oxford undergraduate to achieve a Double First after Maths and Philosophy were offered as separate degrees. The following year this precocious friend of Lord Byron (‘I was always in scrapes, Peel never’) became an MP at 21. By 24 he was Chief Secretary to Ireland.

Backbencher Rees-Mogg still awaits destiny’s trumpet at 49, an age when Peel had already been prime minister once, albeit briefly. But the eye-opener lies in the substance of Mogg’s implied reproach to Peel. There can be no denying he was a cold fish, brusque and awkward with friend and foe alike in a Heath-ish way. But he mastered the Commons for 20 years by mastering every brief he had to handle, from the 1832 Reform Act and Catholic emancipation – he pragmatically changed sides on both – to repeal of the Corn Laws, the urgent dilemma which prompted his most famous U-turn.

The Corn Laws had been imposed in 1815 after the disruptive and costly Napoleonic Wars as an act of blatant protectionism for distressed domestic agriculture. They protected rich landowners and their tenant farmers from foreign competition (by fixing the minimum price at which grain could be imported), but did so by means of dearer bread for industrial England’s increasingly restless poor and, after 1845, the famine-hungry Irish.

It was all made worse by a wet summer and bad harvest in 1845. As well as radical Chartism, the growing crisis triggered the formation of a middle class Anti-Corn Law League by the sort of citizens who make up the People’s Vote campaign today, outward-looking and progressive, George Eliot-types, nowadays Guardian or Times reading folk.

Yes, as PM from 1841 until his fall in 1846, Peel split the Tory party which did not win another Commons majority until 1874. But he was right on the issue, his opponents – the landed aristocratic interests and the stupid wing of the Tory party crying ‘betrayal’ – were wrong. Then as now, they set themselves up against the industrial interests, showing what Nicky Morgan this week called ‘contempt for business’. No wonder they lost power for 28 years! No wonder business leaders on Tuesday again signalled mounting impatience with the pace of Brexit clarity.

Rees-Mogg and his crew, some wealthy finance capitalists like himself – not much ‘march of the makers’ among them – present themselves as free trade globalists. But they find themselves allied with arch-protectionist Trump. His emerging tariff war with three continents is likely to damage left-behind Trump voters as surely as most surveys confirm that Brexit will most damage Leave-voting areas. The private equity cowboys may stalk May, but nationalist thugs stalk them, waiting for the moment when it all comes unstuck.

Brilliantly orchestrating the romantic and reactionary campaign’s doomed attacks on Peel in 1846 was a rank outsider, a rackety romantic, an ethnic Jew and – worse – a novelist, Benjamin Disraeli MP. Two years ago we might have likened rackety Boris to Disraeli, but Dizzy’s lack of fixed principles would not debar him from a dazzling future: PM in 1868 and 1874-80, a peacemaking European hero at the Congress of Berlin. It’s all over for Johnson. Even the regular ConHome leadership poll now has Michael (‘Trust me’) Gove with twice as much support among activists. In Commons corridors Govey is market-testing the idea of abandoning HS2 to free up some Brexit cash. Charm-free Sajid Javid is ahead of him and Johnson, which must help May get a good night’s sleep in Sonning Common.

Can O’Mogg’s expensive mirror in his own non-ancestral home at Gournay Court reflect back the notion of Jake as Disraeli to May’s clumsy Peel? We may discover if there is substance beneath his stork-like attitudinising in the coming Brexit months. But Mogg, like David Davis, the serial almost-resigner, makes threats, then pulls back. Merciless in debate, Disraeli had no such inhibition. In any case, free market Mogg has expediently placed himself on the protectionist side of the Corn Law argument to get him through a 900-word Telegraph column. Pure Boris, mere words.

Yet we should tarry a moment longer in the 1840s. There is much of the mid-19th century’s fluidity and instability in today’s Westminster. By then governments that had once been sustained by royal patronage and fixing were moving towards a system sustained by party discipline, electoral machines and the popular cult of the leader. Faced with widespread social distress the old order needed to adapt and change in the 1840s – much as it does now when a century of relatively stable, alternating-party government looks on the edge of collapse.

Not just in Britain either. Merkel teeters on the brink of political death after forgetting her own advice not to repeat the Thatcher/Kohl mistake and stay too long. Matteo Salvini, Italy’s new right-wing interior minister, has withdrawn threats he made in the election campaign to leave the euro.

Instead he seeks to disrupt the EU’s way of doing business from the inside. Forging populist coalitions with former Warsaw Pact members – Hungary, Slovakia and Poland – against immigration and austerity at the Council of Ministers table in Brussels is his way forward. Austria’s Sebastian Kurtz is up for it too.

After years of failed attempts to resolve the immigration crisis on the EU’s southern border and do so by burden-sharing – over which Silvio Berlusconi was rebuffed a decade ago – the summiteers’ language is now much tougher. Once unthinkable, border camps to contain asylum seekers until they can be processed and sent back to where they first claimed asylum – theoretically part of EU migration law since the 1990 Dublin accords – are now official policy if member states actually do what they sign up to. Renationalising migration policy, away from Schengen ideas of a borderless Europe now looks the way forward – three years too late for David Cameron.

At last month’s mini-summit in Berlin’s Schloss Meseberg, Merkel and Emmanuel Macron – the one who still talks the integrationist talk – put a brave face on firing up the stalled engine of Franco-German cooperation, still holding out the prospect of making Frontex a ‘genuine EU border police’.

Will the EU centre hold? Throw the bundle of contradictions that is Trumpismo into the mix and our rules-based multilateral world looks close to being turned upside down.

Perhaps it will be and perhaps not. None of the new generation of EU nationalist leaders yet say they want to leave Europe, not even the austerity-ravaged Greeks. But the nationalistic mood of their electorates, stoked up on grievance, will make it harder for their leaders to sanction any Brexit deal which seems to favour Britain, unless it can be dressed up as protecting their national interests too.

All this will require delicacy and subtlety, not qualities in abundant evidence on either side of Michel Barnier’s negotiating table. The shambolic state of May’s divided cabinet cries out for a change of leader or a change of government. But the two-party pendulum which emerged from Peel’s Corn Law crisis and the rapid expansion of the Victorian electorate (one of Dizzy’s stunts) seems to be stuck. If the shambolic Tories are ahead in the polls, despite everything, it suggests little public enthusiasm for Jeremy Corbyn to lead us out of the Brexit quagmire.

The Labour leader is under growing pressure, not just from Labour ‘centrist dad’ MPs, but from those Momentum activists and from big unions, to abandon his fence-sitting feebleness and make more than vague formulaic proposals about a ‘jobs-first Brexit’. It can be done.

Tucked away in the Osborne-edited London Evening Standard last week was an all-too-rare detailed list of practical compromises that might seal a mutually acceptable deal. It was penned by George Bridges, who resigned in despair as a Brexit minister last year, and was pragmatic to a Peel-ite fault.

Needless it say, it passed largely unnoticed by all concerned.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37