MICHAEL WHITE on how distractions are diverting us from the issues central to humanity’s survival and dissipating attention from the real issues.

What do Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson and Yuval Noah Harari have in common? I agree, not much. One is a clever and famous chap who has frittered away his talents writing frivolous books like Seventy-Two Virgins and Have I Got Views For You. The other is also famous, a public intellectual who has written scholarly volumes like Sapiens and Homo Deus – and worries about the future beyond his own career ambitions.

I was half wrong here last week when I dismissed de Pfeffel’s £5k a pop ‘Burkagate’ column in the Telegraph as destined to damage his political hopes (I hesitate to call them anything as organised as ‘plans’). Like a wit once said, no one ever went broke under-estimating the intelligence of the public. The wit might have added ‘or of the newspapers’, at least in the silly season. But I suspect the quote originated with the acerbic Baltimore columnist, HL Mencken, who took his trade quite seriously.

Where I still insist I was right in last week’s New European is in standing with those who argue that the portly plotter stumbled into his ‘letterbox’ controversy. He merely took advantage of it when he realised that refusing to apologise to Theresa May – and her attack poodle, party chairman, Brandon Lewis – would restore lustre to the ‘Brexit Martyr’ crown he tarnished with his botched resignation as our work experience foreign secretary.

We cock-up theorists are probably a minority on this one in these paranoid and demented times. It is more fun and provides more scope for outraged, highly-satisfying displays of selective intolerance to assert that Johnson planned the whole thing rather than sought to cover the offending column’s essentially liberal point – don’t ban the burka – with mockery of said headgear.

In its most extreme form the conspiracy theory has Burka Boris taking dictation from dog whistler, Steve Bannon, the American nationalist with whom he has struck up an improbable working acquaintanceship. Keep your distance, BoJo. Muscular and unshaven ex-marines with serious anger management problems like Bannon sprinkle posh fat boys like you over their breakfast cereal. Personally I think Boris was writing in a hurry and reached for a sub-standard joke.

Where does earnest and admirable brainbox YN Harari fit into this undignified manifestation of the ugly culture war which Comrade Steve has helped to export across the Atlantic? Good question. The answer is that one of Harari’s themes on his current book promotion tour – the book is called 21 Lessons for the 21st Century – is that resurgent, populist nationalism is a noisy distraction from the imperative big issues we should all be worrying about.

Need you ask what they are when a heatwave has ravaged the northern hemisphere’s summer? Climate change, disruptive technologies driven by artificial intelligence (AI) and bio-engineering that also has the potential to tweak our very nature, liberate us from fear and want – or wipe us out. We are about as prepared for all this, Henry Kissinger recently remarked, as the Incas were for the Spanish Conquistadores, armed with guns and small pox. He might have added ‘or the Titanic for the iceberg’.

Odd that the self-appointed futurologists of Brexit have so little to say about such clear and present dangers in their learned papers, apart from a nod to algorithms. They offer glib assurances that smart customs software will allow us to trade safely and quickly across frontiers without ro-ro lorries at Dover queueing all the way back to the M25. Dover port authorities don’t seem to agree. Nor does business in both halves of Ireland.

Smart customs solutions run alongside Brexit scorn for man-made climate change, of course – science-resistant scorn which mostly rests on optimism and assertion. It’s much like Iain Duncan Smith’s simplistic hopes for universal credit (UC) in the face of expert warnings. Its ‘transitional’ implementation is currently causing much distress to society’s needy, but not much to resigner IDS whose private welfare network includes living in his father-in-law’s house, leaving others to clean up the UC mess. Very Brexit.

Sorry to sound grumpy. But that’s the thing about populist politics, not just today but forever. They live by headlines, they make promises, declare victory and move on. Sanctions, trade wars, peace talks, ‘war’ on over-priced US pharmaceutical firms, Donald Trump does it all the time. Any evidence of failure can be attributed to enemies, the ‘fake news’ media or those ‘left wing Democrats’ though, oddly, never Russia. If Brexit goes badly I fear you, dear TNE reader, will be in the frame.

I wish I could say that my side in most of these controversies was qualitatively better, but it isn’t, not as much as I’d like. I share the overall view that the prospect of Brexit is causing cumulative damage to the UK economy, but not all the news is bad. We clocked up 0.4% growth in Q2, better than France, worse than Germany, and Remainers (who predicted it would be so much worse much faster) are sometimes too grudging.

It’s counter-productive. As such it’s a bit like Corbyn-led Labour blaming everything – even the endemic problems of rough sleeping or A&E waits – entirely on the government and austerity, or blaming the shabby shambles over anti-Semitism and Tunisian wreath-laying parties solely on a media vendetta and (copyright Chris Williams MP) panic in the ‘neo-liberal establishment’.

Let’s not go there. It’s not that Johnson’s burka row or Jeremy Corbyn’s quixotic past as an armchair revolutionary (personally, he’s opposed to violence, we are constantly reminded) are without significance. It’s just that they are blown out of proportion by people with unrelated agendas – ‘Get Boris’ and ‘Get Jez’ – whose personal record is not without blemish. Yes, I mean you, Bibi Netanyahu. But I don’t mean you, Dominic Grieve, you’re unusually fastidious. When you say you will leave the Tory party if young de Pfeffel – ‘not a fit and proper person’ – becomes its leader, I believe you. That’s increasingly rare in Twitter-driven 2018.

Is there light at the end of the tunnel that isn’t flames, a silver lining to the mid-August cloud that isn’t lightning? The Observer certainly thinks so. On Sunday it published research by Focaldata, a consumer analytics company, by modelling two YouGov polls (total sample 15,000) before and after Theresa May’s Chequers plan was published on July 6.

Combining them with census data and material from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) they concluded that in 112 of the 632 constituencies in England, Scotland and Wales a majority of voters had shifted from Leave to Remain – 97 of them in England, 14 in Wales (which also voted for Brexit). That means there are now 341 seats with a pro-Remain majority, compared with 229 at the time of the referendum, 288 pro-Brexit compared with 403 in 2016.

Best for Britain, the pro-People’s Vote umbrella group, and anti-racist campaign, Hope Not Hate, felt the research shows that Brexit is not inevitable and that people are having second thoughts – especially in the Labour-dominated North of England – about the realities of what it might mean. That should boost resistance in key votes this autumn in both the Lords and the Commons.

Pro-Remain MPs, the people who fight elections, were more tentative. There is some polling evidence of a slight shift back from the 51.8% – 48.2% result on June 23, 2016. But like the binary Tory-Labour poll, it is fragile, and those MPs who fear a second referendum would be a fearsome gamble have my vote.

Despite grassroots and union pressure in the run-up to the party conference season, Labour’s deliberate equivocation on Brexit is unlikely to change under Corbyn’s leadership. Its attitudes are deep-frozen as anti-capitalist, anti-EU, anti-US during the Cold War. The fact that the chaotic and divided Tories (voters are even more pro-Brexit than before, reports Focaldata) are not 20% behind but are occasionally even ahead of Labour, is also pretty salutary. In any case, the justification for Labour’s fence-sitting, that 30 or so key seats have Brexit majorities, was always suspect. They were not Labour majorities and Focaldata says that Frank Field, Graham Stringer and Kelvin Hopkins, three prominent Leavers, now sit for Remain seats. Not that it stopped Kate Hoey, whose Vauxhall seat always was.

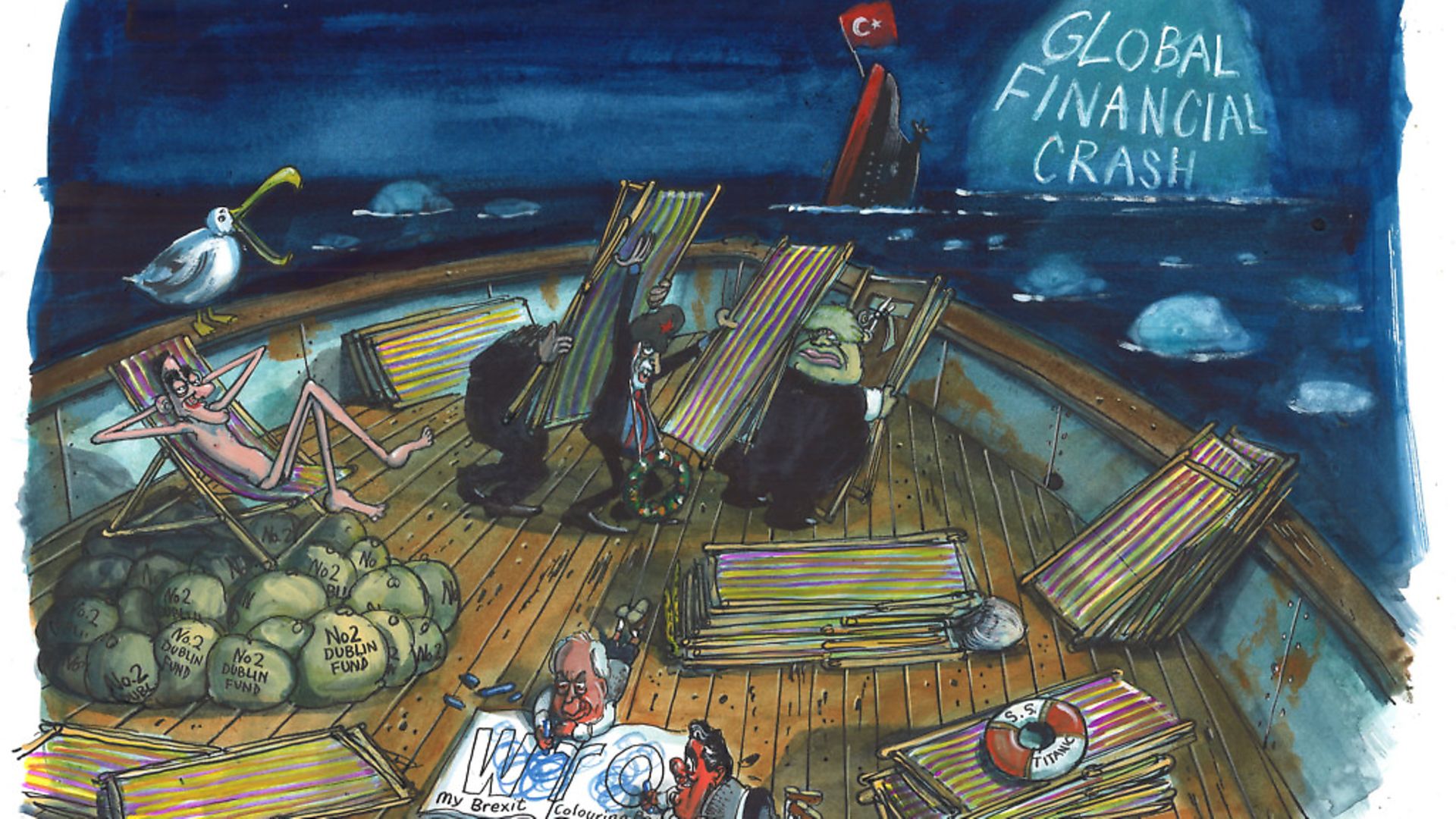

My own oft-repeated feeling is that it would take a serious world crisis to shift public opinion decisively back into the ‘better the devil you know’ safe harbour of the EU, rather than to risk an open voyage in the SS Brexit, whose senior officers sometimes sound as confident as Captain Edward Smith on the bridge of the Titanic in 1912 – symbol of over-mighty European pride that it soon became, as war engulfed us all.

No single factor can be blamed for the sinking. It wasn’t just the iceberg, any more than the assassin’s shot at Sarajevo caused the First World War. It’s sometimes called an ‘events cascade’, where a lot of things suddenly go wrong – sometimes in August. Are we seeing one such event this week, as Trump’s confrontation with Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, over trade and controversial clerics, rapidly escalates?

Probably not. The smart money tells us that Erdogan will have to compromise with reality, by allowing the Turkish Central Bank to raise interest rates, and easing up on his ‘foreign enemies’ rhetoric – as well as phoning the IMF to help with those dollar-denominated debts as the local lira tanks.

But the Brexit vote and Trump’s reckless policies (to name but two) remind us that political grandstanding is in fashion. Why should Erdogan, a talented politician with no handbrake, be any different. Having concentrated power on himself, most of Turkey’s economic problems (not the three million refugees) are seen by sensible Turks to be of his own making. Cornered, why shouldn’t he lash out against perceived Western hypocrisy (some of it true) and negotiate help-at-a-price from fellow autocrats in Moscow and Beijing? That wouldn’t do Nato much good. The Chinese are already all over EU-impoverished Greece.

Market contagion is already affecting other emerging economies as nervous investors seek safety in the US dollar, the value of which Trump’s credit card splurge has raised. The White House is also feuding over trade and other sanctions with China, with Mexico and Canada, with Russia (at Congress’s insistence, not the president’s) with Iran and with the EU. Isolated Britain is caught in several pincers: which side to choose.

Shrill nationalistic self-assertion is also politically contagious. Under the high-speed ‘reform’ leadership of Prince Salman, the only leading prince to have been educated only in introspective Saudi Arabia (so he speaks poor English), Riyahd has picked a bizarre fight with studiously inoffensive Canada. Hungary, Poland, Italy… they’re all at it – usually as a distraction from the domestic failures they promised to cure if elected. A case of ‘no bread and circuses’.

Optimistic American conservatives try to make the best of what they know is a bad job. People like Kissinger persuade themselves that some good may come of this disruption – we might call it ‘the great immoderation’ – so that complacent organisations like the UN, the WTO, the EU and Nato may benefit from a good Trump kicking. Well, maybe. Remain ministers like Jeremy Hunt and Sajid Javid, who have since declared for Brexit, are engaged in the same hopeful exercise.

Yet we rarely get a mention, in learned papers from Economists for Brexit (now known as Economists for Free Trade), of this rising economic and political nationalism, of trade wars and assaults on the rules-based world order. It has taken 70 years to construct, but can be demolished much more quickly – rather like that row of retirement homes that a disgruntled building worker took a mechanical digger to.

On Tuesday, Lord (Peter) Lilley, one of Brexit’s more thoughtful champions, penned a column for the Times arguing that, in the absence of a sensible trade deal with Brussels – Chequers is ‘moribund’ and the Irish ‘backstop’ unacceptable – it would be best to leave on WTO terms.

WTO rules would prevent the EU from discriminating against us so there will be no Lawson cliff to fall over. Tariffs will only be 4%, non-tariff costs 0.1% according to the Swiss (!!) and any extra burden offset by the 15% depreciation in sterling. Britain would save its £40billion ‘divorce’ bill and our old friend electronic customs collection will prevent nasty queues at Dover.

Anything less than ‘good neighbourliness’ in Calais and beyond would breach EU law, WTO rules and the new trade facilitation treaty, says Lilley. Good oh! But earlier in the week the Times also reported that the EU’s no-deal planners, led by Martin Selmayr – Juncker’s brain – are concerned about that March 29 cliff. Britain, a single, non-federal state, is better placed than all 27 EU member states to make the regulatory changes that will allow goods to flow and aircraft to keep flying, the report suggested.

True or false, we may find out the hard way. Much of what Lilley wrote seems to come from what Economists for Brexit like to call – it sounds more positive – a World Trade Deal – in reports like What If We Can’t Agree? It would be making a Paul Dacre kind of mistake to say it doesn’t make some good points. For example, EU regulation does add costs to businesses which don’t trade abroad. But a 6% loss of GDP sounds a stretch.

So we are invited to believe that a ‘Brexit in Name Only’ deal would costs the UK 7% in lost GDP growth, whereas the WTO route would see consumer prices fall by 8% and GDP rise by 4% over a medium period, 7% if other savings are taken into account. EU exporters will have to cut their prices to compete. The Treasury will gain £13billion in extra taxes. Professor Patrick Minford even estimates that leaving early – with no 21 month transition – will be worth £650billion to the UK.

You may have noticed that these estimates mirror the 7% loss of GDP made in the leaked civil service report on a no-deal Brexit. Without bothering to raise an eyebrow over the Minford School of Maths – devoid of any reference to the trade war world out there – I work on the assumption that both rival versions are likely to prove wide of the mark.

But they do underline Professor Haravi’s point about distractions which divert us from the issues central to humanity’s survival. Squabbling over the sun loungers on the SS Brexit (over burkas and Tunisian wreath laying) also dissipates attention available for more humdrum challenges: the housing shortage, HS2 and the third Heathrow runway, the chaotic and avoidable state of rail management, the probation service, airport queues and whether or not Brits will be given their own as a Brexit reward.

The response of both government and opposition to them all is usually painfully inadequate. Lost opportunity costs are another form of cost which don’t feature in Economists for Brexit’s posh populism.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37