Fifty years on from the moon landings, MICK O’HARE asks whether this monumental achievement – the ‘giant leap for mankind’ – was ultimately worth it

It’s obvious that Joe Gilmore, head bartender at the American Bar in the Savoy Hotel in London thought it was all worthwhile. Just before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in July 1969 he created the Moonwalk cocktail, a drink still on the bar’s menu today. So impressed by his creation was Gilmore, and so keen to promote it, that he had the ingredients shipped to the US so that the first alcoholic drink Armstrong would enjoy on his return was the Moonwalk’s mix of grapefruit, Grand Marnier, champagne and rose water. There’s a framed letter in the Savoy’s museum from the astronaut thanking Gilmore, although there’s probably no substance to the rumour that Armstrong preceded his cocktail with the words “one small sip for a man…”

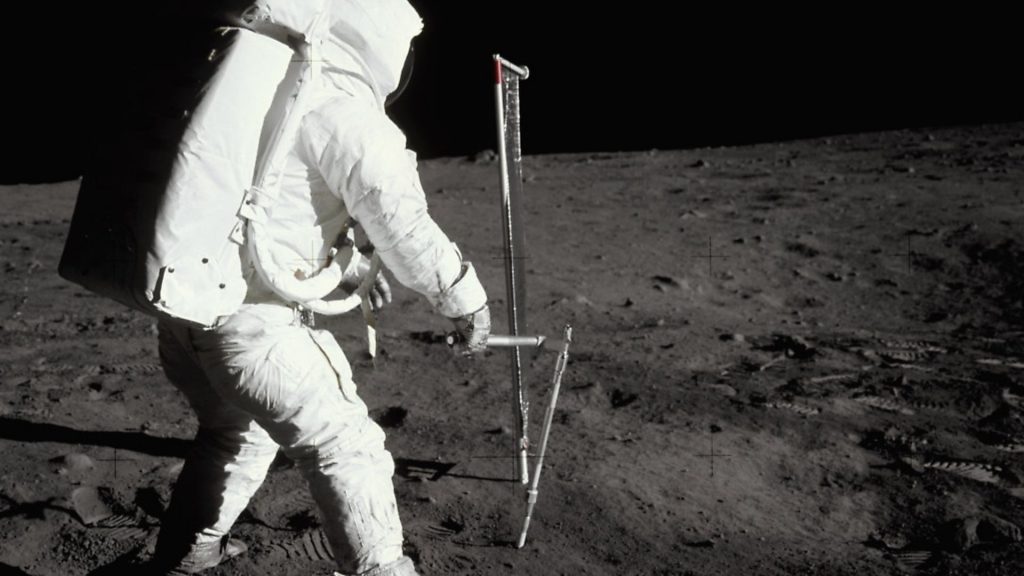

Presumably when the Apollo 11 commander stepped onto the surface of the moon on July 21, 1969, booze was the last thing on his mind. It was the culmination of a decade of endeavour. In 1961, president John F Kennedy had promised a moon landing by the end of the 1960s, so with his now immortal line “one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind” (there’s still debate about the ‘a’) Armstrong ensured the Americans just scraped home.

But now, 50 years on, and with nobody having walked on the moon since 1971, it’s pertinent to ask whether the whole thing was worth it. What was it for? Was it, to coin a bad cliché, worth a handful of moonbeams?

It was, of course, a success born out of Cold War ideology – a means of proving that American democratic capitalism was better than Soviet state-controlled collectivism. But how and why does walking on the moon prove that? Certainly the British weekly science journal New Scientist was sceptical, writing that NASA’s achievement was “a matter of no greater moment than just peering into the high recesses of the big top and there witnessing the most incredible trapeze act ever performed”.

Why risk humans and all the cost it entails when we could have done real science with an un-crewed probe, it asked. So disparaging was New Scientist of Apollo 11 that on the 40th anniversary of the landing, it issued an apology for being so curmudgeonly first time around. But the magazine wasn’t alone. A substantial proportion of the world’s scientific community saw putting humans in space as a costly and risky waste of time, arguing the money would be better spent on earthbound projects. And the questions still stand. What was it all for – a vainglorious project, a sideshow to the Cold War? Or, to turn the arguments on their heads, was it something that benefitted science and humanity and still does today?

Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo spacecraft collection at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC and an expert in the politics and diplomacy of spaceflight, believes that whatever drove humans to the moon the collective effort stands alone.

“The United States directly and indirectly employed 400,000 people on Apollo, their jobs, their livelihoods were entwined with the project – often at great family cost as they worked endless hours. It gave them a sense of purpose. You’d obviously have to ask each one of them but I think you’d find that they thought it worthwhile, the highlight of their careers.”

So was their motivation to beat the Soviet Union or were there more subtle drivers? “In many cases the Apollo team were driven by a sense of national service and national pride,” says Muir-Harmony. “Frank Borman, who flew on Apollo 8, is quite explicit about this. He saw it as part of serving in the military and serving his country amid the Cold War, answering Kennedy’s inauguration address: ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country’. But others also enjoyed the technical and logistical challenge of getting humans to the moon.”

But does any of this make it worthwhile with the benefit of hindsight? How does getting to the moon first prove that the victor’s ideology is better than the loser’s? “It doesn’t directly,” agrees Muir-Harmony. “But you have to realise the shock that went through the US administration when the Soviet Union put Yuri Gagarin into space in spring 1961. People around the world marvelled at the accomplishment. They looked up to what the Soviet Union had achieved.

“It was also days before the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba by US-backed rebels and Kennedy realised the US needed a change of image and focus. He suddenly saw the technological prestige that spaceflight offered. And getting to the moon was the biggest prize in space.

“At heart Kennedy was an internationalist who believed American values would offer the world better solutions than the Soviet Union could. Getting to the moon first does not prove your ideology is better but it does impress the international public. As his successor as president, Lyndon Johnson, later said, you get geopolitical alignment behind a nation that can do such things.

“It’s about the perception of America around the world – we’d probably call it soft power today. And as an instrument of soft power is the context we perhaps should view Apollo in 50 years later.”

However, some devil’s advocates have suggested that Americans landing on the moon proved very little about democracy considering they were state employees. How, they have asked, does a state agency (NASA) sending state employees (the Apollo astronauts) to the moon differ in any way from the state-run space programme of the Soviet Union? Private enterprise got nobody to the Sea of Tranquility.

“I think the US State Department and NASA would point out their programme was open for the nation and world to scrutinise, the Soviet Union’s was not,” says Muir-Harmony. “And private enterprise had a big role, it wasn’t just the state. Of the 400,000 people involved, only 25,000 were government employees the rest worked for private companies.”

Space historian and author Gerard DeGroot has written that Apollo was driven solely by Cold War pragmatism and the need to provide the American and worldwide public with heroes who would show the world the virtue of US-style democracy and freedom. Of course, to a point he is correct, and Kennedy clearly realised this too, but is DeGroot, like so many others, labouring under a misconception? The world did not watch agog because it was desperate for an ideology to succeed. People would have watched whoever was first onto the moon. It was the technological and human achievement that mattered at that moment – even the grumpy New Scientist admitted this.

“Absolutely,” says Muir-Harmony. “While Neil Armstrong would not have walked on the moon without the Cold War, the accomplishment still stands astride that. It provided the first global television audience, and was an achievement, to use the phraseology of the time ‘for all mankind’. Kennedy was keen for it to be seen as something for all the people of the world. Up to 600 million people watched it – with more listening on radio – and we are still talking about it today. For many people it was a milestone moment in their lives. It was cited as ‘a new beginning’ for humanity – some even called it Moon Day 1.”

It’s true that despite the Cold War overtones of the space race, many in NASA and the US government were keen to see Apollo 11 as an internationalist mission. There were even controversies about whether the astronauts should plant the United Nations flag rather than the Stars and Stripes.

In the end the US flag won out but the plaque the astronauts left on the moon announces they came “in peace for all mankind” and shows the two hemispheres of Earth with no political boundaries. “They made clear,” says Muir-Harmony “that they were not claiming the moon for the US. NASA even had a ‘symbolic activities committee’ to oversee whether these ideals were being met. In that era internationalism was seen as a positive. The US was involved in aid programmes such as the Alliance for Progress – a kind of Marshall Plan for South America – and saw its role as a benign power forging links with other nations with whom it could create alliances.”

There are also arguments made about the sheer pointlessness of going to the moon in the first place. Much has been made of Armstong’s fellow moonwalker Buzz Aldrin’s description of the lunar surface as “magnificent desolation” and that this suggests there was nothing on the moon to make it worthwhile visiting. But nobody climbed Everest for its practical worth, and very few people use ‘magnificent’ pejoratively. Whatever the astronauts discovered, their achievement in getting there is arguably far greater than any economic value.

“It’s too simplistic to say that nothing came of it, that it was worthless,” agrees Muir-Harmony. With hindsight we can put whatever values on Apollo we choose to but it had profound effects and “it helped to change geopolitics. Richard Nixon had become president when Apollo 11 landed and he used its success to change his relationships with other nations, China and North Vietnam being especially important because the Vietnam War was still being fought.”

When Armstrong returned from his postflight worldwide trip Nixon told him it had finally secured him a meeting with hardline communist Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu. “Nixon said to Armstrong that this alone made Apollo worth every cent,” relates Muir-Harmony.

“Although we often talk of technological spin-offs from the space race there were political spin-offs too. Nixon travelled the world in the aftermath of what we now call his ‘moonglow’ tour.”

And what of that financial cost? Well of course there will always be calls for all the resources ‘wasted’ and the money that was spent to be directed towards hospitals, cures for cancer, education, alleviating poverty… the list is pretty much endless. And the Apollo programme was wound down in 1971, the last three missions cancelled when it became clear the government and American people no longer considered it worthwhile.

They wanted their tax dollars spent elsewhere while there were earthbound political issues such as Vietnam, and the burgeoning civil rights movement to deal with. But can simple monetary worth ever fully account for human endeavour? Let’s not forget the space race was accompanied by a destructive arms race back on earth as the two superpowers stockpiled nuclear weapons and fought proxy wars around the globe in an even deadlier competition for ascendancy.

As Doug Millard, senior space curator at London’s Science Museum has pointed out: “If space really was a proxy for an actual war between the US and the Soviet Union, then it was surely money well spent. Millions of lives were saved, and we ended up with a whole load of science and great stories.”

Muir-Harmony adds: “If we view Apollo in the context of national security, rather than money lost that could have been spent on hospitals or education, then the cost focus shifts. It wasn’t a trade-off between health or education and egotistical grandstanding. It shifted the perception of people politically, and instead of the US and Soviets coming to blows on earth, they showed what could be achieved elsewhere. Positives rather than negatives.”

So, 50 years on, what is the greatest legacy of Apollo 11? “Scientifically, I’d say it was confirming the origins of the Earth-Moon system through the geological samples the astronauts brought back,” says Muir-Harmony. But on a political level she agrees with Millard’s point. “The Cold War was raging, there were nuclear weapons and proxy wars around the world. Apollo focused on a positive and in many ways drove political realignment. That psychological battlefield, winning prestige and winning public opinion was so significant, and for those who say it cost too much I disagree, it warranted national resources,” she argues. “And let’s not forget that for the first time we could see the world from space with no political boundaries. As the astronauts said, if we could bring the politicians up here peaceful co-existence would be far more likely. This is our planet, the only place we can live, we need to protect it.”

Whatever the motivation, ultimately it was the achievement that dwarfed the ideology. Armstrong, Aldrin and their colleague Michael Collins – who flew the mission’s command module alone in lunar orbit while the other two were on the moon – became heroes despite the Cold War, not because of it, and were lauded in the Soviet Union as much as they were in the United States. Like Yuri Gagarin before them, they became citizens of the planet.

Apollo 11 captured the imagination of the entire world. Millions of people bought televisions for the first time so they could witness history being made, while others gathered in public squares in their thousands to watch on large screens. Science rarely makes the headlines yet this was the biggest story ever. So while it was, of course, the culmination of the space race, the ultimate propaganda tool of the Cold War, and quite obviously an ideological mission more than a science mission in the end, New Scientist’s grinching failed to take root.

Despite the race to the moon being driven by politics not scientific research, and perhaps by nationalistic pride rather than the common purpose of humanity, we can see it now – especially in the light of almost five more decades of astonishing scientific progress – as still humanity’s finest technological achievement.

Whatever the misgivings, and there have been many, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins were participants in what many people would consider to be the greatest adventure in history. Joe Gilmore would drink to that.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37