MITCH BENN takes a look at the end of an eight year era as Game of Thrones comes to an end and explores how the ending for our own story has not been written.

So, Game of Thrones then.

I’m going to go out on a limb here and assume that a worthwhile percentage of you have been following GoT (as it’s usually abbreviated to for internet purposes) for some if not all of its eight-year run, which came to an end earlier this week.

Those of you who haven’t been watching; I’m not going to try to shame you into it now… The show managed to transcend a lot of the snobbery exhibited towards high fantasy in the mass media to reach a far broader audience than even HBO could have anticipated. But it’s not, by any means, everyone’s cup of tea, so if you’ve been avoiding it for eight whole years I imagine you have your reasons and I respect those (probably).

Even the non-Thrones enthusiasts among you may have picked up on the fact that the show’s finale – the whole of the last couple of seasons in fact – hasn’t met with the universal approval of the show’s hardcore fans.

Without wishing to spoil it (there may be those among you who haven’t yet seen the last episode but still intend to) I found it broadly satisfactory without being mindblowing.

This seems of a piece with the story as a whole. The show, and George RR Martin’s books, present such a morally complex and fluid world (much like our own, except with dragons) that a straightforward And They All Lived Happily Ever After was never really on the cards. What we got was probably the closest thing possible.

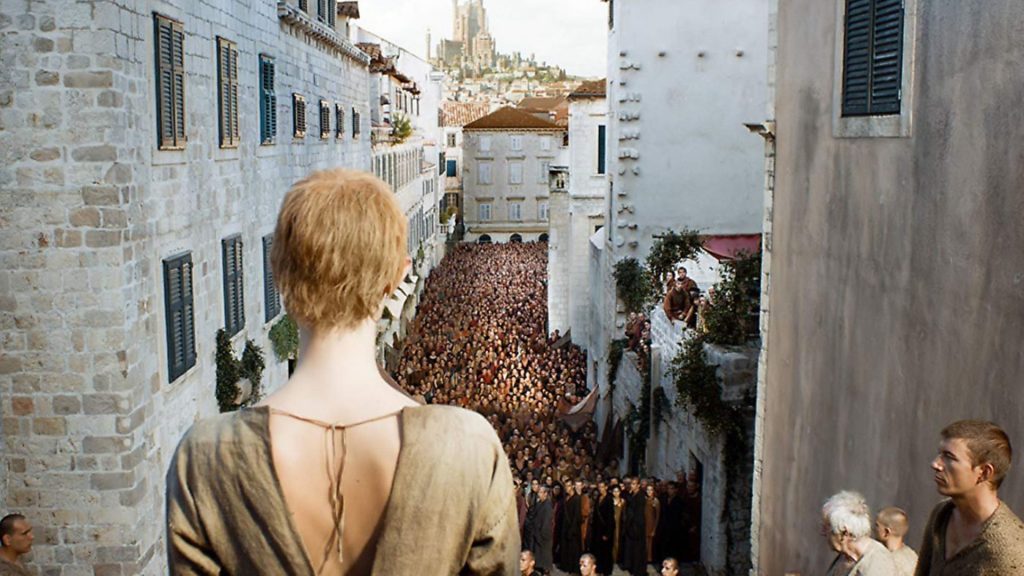

The story, in case you don’t know, concerns the years-long war between the various noble houses of Westeros, a mythical kingdom perhaps best described as “14th century Britain turned up to 11”.

Right from the first moment (and page) it’s clear that this is going to be a story which ignores most of the ‘rules’ of storytelling. Bad deeds go unpunished; the innocent suffer unjustly; and every time a brutal or foolish king or other such ruler is removed from power they’re invariably replaced by someone far worse.

The very first episode ends with the apparent murder of a young child and the first season ends (slight spoiler alert, but it’s been eight years, you must have heard about this by now) with the apparent hero of the piece being executed, whereupon you realise that he wasn’t really the hero, that there may indeed not be a hero and that the fact he was being played by Sean Bean should have made his fate obvious from the start.

One of the story’s recurring themes is that there are no real heroes and saviours will always let you down. You may have picked up on a specific burst of fan outrage after last week’s penultimate episode, in which one of the prime contenders for saviour of the kingdom and rightful heir to the throne ruined everything by going off on a genocidal rampage.

Some viewers seemed to think this came out of nowhere, but that character’s defining trait in these later seasons has been increasingly unshakeable belief in their own righteousness. As I’ve said in this column before, with reference to more earthly events, unshakeable belief in one’s own righteousness doesn’t inevitably lead to atrocity, but it is a necessary first step. All the worst crimes in history were committed by people and armies who believed 100% that they were doing the right thing.

Besides, it’s never easy to reconcile the desire to grant readers (and viewers) a ‘happy ending’ with the desire to remain faithful to the reality one’s created. I’m just finishing writing the third book in my Terra science fiction trilogy and it’s hard to bring the story to a satisfying conclusion without undoing much of the world-building I’ve already done.

Because even – perhaps especially – imaginary worlds should feel real while the viewer (or reader) is ‘in’ them, and the sad fact is that in the actual real world there are no happy endings.

Endings, by definition, are always sad. Happiness doesn’t take the form of endings, but of agreeable ongoing situations, which are always at least slightly tainted by the knowledge that they won’t be ongoing forever. As my daughter Astrid noted when she was about seven: “They always end stories with ‘and they all lived happily ever after’ but that’s not true is it ‘cos they are all gonna DIE eventually.”

I imagine by the time you read this you’ll have voted (or be about to vote) in the European elections. Perhaps the results are coming in. Perhaps some people are claiming victory who we’d rather had been soundly defeated. Perhaps they’re proclaiming that this means the battle to avert Brexit is finally over. They’re wrong.

Just as a good storyteller knows that the story is never really ‘over’, just resolved for a while, we know that this story – our story – is only just beginning.

Resist. And valar morghulis.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37