Muhammad Ali took part in some of history’s most memorable fights. One of his least remembered took place 45 years ago this week. It was certainly the most bizarre of his long career, and also one of the most consequential

There are many ways to remember Muhammad Ali: cocky, young rapping poet; outspoken political and cultural icon; arguably the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time. But skipping around the ring trying to avoid the kicks of a Japanese wrestler lying on the floor? That’s probably not one of them.

Yet that’s exactly where Ali found himself in June 1976, two years after his defeat of George Foreman in the Rumble in the Jungle and just eight months after he outfought the late Joe Frazier in the Thrilla in Manilla.

The unlikely match-up between Ali and Antonio Inoki came about after Ali met the president of the Japanese Amateur Wrestling Association, Ichiro Yada, at a reception in New York in 1975 and asked if there was no Asian fighter willing to take him on. “I’ll give him one million dollars if he wins,” said Ali.

When Yada returned to Japan, Ali’s remark made headlines in the Sankei Sports newspaper. Inoki a highly respected figure in his home country and wrestling’s world heavyweight champion started pursuing Ali intent on making the fight happen.

A few months later, in June, Ali stopped in Japan on his way to fight Joe Bugner in Malaysia and during a press conference he received a ‘response’ from Inoki, who accepted his challenge. Ali’s manager quickly denied that the fight would take place, but Inoki kept up the pressure, producing an English-language pamphlet imploring Ali not to “run away”.

It paid off and by March 1976 the two fighters had agreed terms to fight for “The Martial Arts Championship of the World”. The date was set for June 26 and the venue was to be Tokyo’s Nippon Budokan arena.

When Ali, then the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world and at the height of his popularity following his victories over Foreman and Frazier, was asked why he was willing to fight a wrestler in a bout that many considered demeaning, his answer was stark: “Six million dollars, that’s why.” Inoki’s paycheque was $4m.

The fight took place against the backdrop of tense diplomatic relations between the two fighters’ countries. The Japanese were still recovering from a series of so-called ‘Nixon Shocks’. In 1971, the US president, Richard Nixon, had imposed a 10% tariff on imports in America, which was explicitly targeted at Japanese products.

At the same time, he unilaterally decoupled the dollar from the gold standard, in effect ripping up the Bretton Woods System of fixed exchange rates and in turn causing the value of the yen to drastically appreciate, further damaging the country’s export market.

Furthermore, it was only four years since the US had returned administrative control of Okinawa to Japan, a legacy of the Second World War. Ali did little to dampen the air of jingoism, invoking memories of the conflict on the morning of the bout when he told journalists: “There will be no Pearl Harbour! Muhammad Ali has returned! There will be no Pearl Harbour!”

Ali had already started calling Inoki ‘The Pelican’ because of his prominent chin. Inoki responded by warning Ali that “When your fist connects with my chin, take care that your fist is not damaged” before presenting him with a crutch to use after the fight.

Interest in the fight was huge. Ringside seats at the Budokan changed hands for up to $1,500 and the fight was broadcast to more than 30 countries and had an estimated audience well in excess of one billion. Many bought tickets to special closed-circuit broadcasts. Fans in Birmingham could pay £5 for the privilege of watching the fight at the city’s Odeon cinema (£7.50 for the posh seats).

Vince McMahon Snr, who went on to make his fortune with the WWE, sold 33,000 tickets to a showing at New York’s Shea Stadium. Unfortunately they were left disappointed by a fight which ended in a draw after 15 turgid rounds; a consequence of the bizarre rules established for the fight.

Boxing journalist Jim Murphy claims that the bout was originally intended to be a ‘worked’ (or choreographed) fight in which Ali would ‘accidentally’ punch the referee, then as he stood concerned over the downed official, Inoki would knock Ali out with a kick to the head.

Thus, everyone would be a winner: Inoki would seal a win on home soil, but Ali would save face because he would have put his concern for the referee ahead of his desire to win. This view seems to be supported by Bob Arum the promoter. However, so this version of events goes, Ali didn’t want to lose, and thus the fight was turned into a real one.

Ali’s doctor Ferdie Pacheco tells a different story: “Ali’s fight in Tokyo was basically a Bob-Arum-thought-up scam that was going to be ‘ha-ha, ho-ho. We’re going to go over there. It’s going to be orchestrated. It’s going to be a lot of fun and it’s just a joke.’ And when we got over there, we found out no one was laughing.”

This is the view put forward by the Japanese media and Inoki, who claimed that when Ali saw him grappling and kicking his sparring partners in training he asked: “OK, when do we do the rehearsal?” When Ali got the answer that the fight was for real, there was a hasty negotiation about the rules, with Ali’s camp, fearful that he might be injured, threatening to call the whole thing off.

Whatever the truth, it was those rules that effectively rendered the fight meaningless. Inoki was not allowed to strike Ali with a closed fist or with a blow to the head (as he would not be wearing gloves). He wasn’t allowed to use any kind of submission manoeuvre nor was he allowed to grapple or try to bring Ali to the ground. If he wanted to kick, he had to do so with one knee on the canvas.

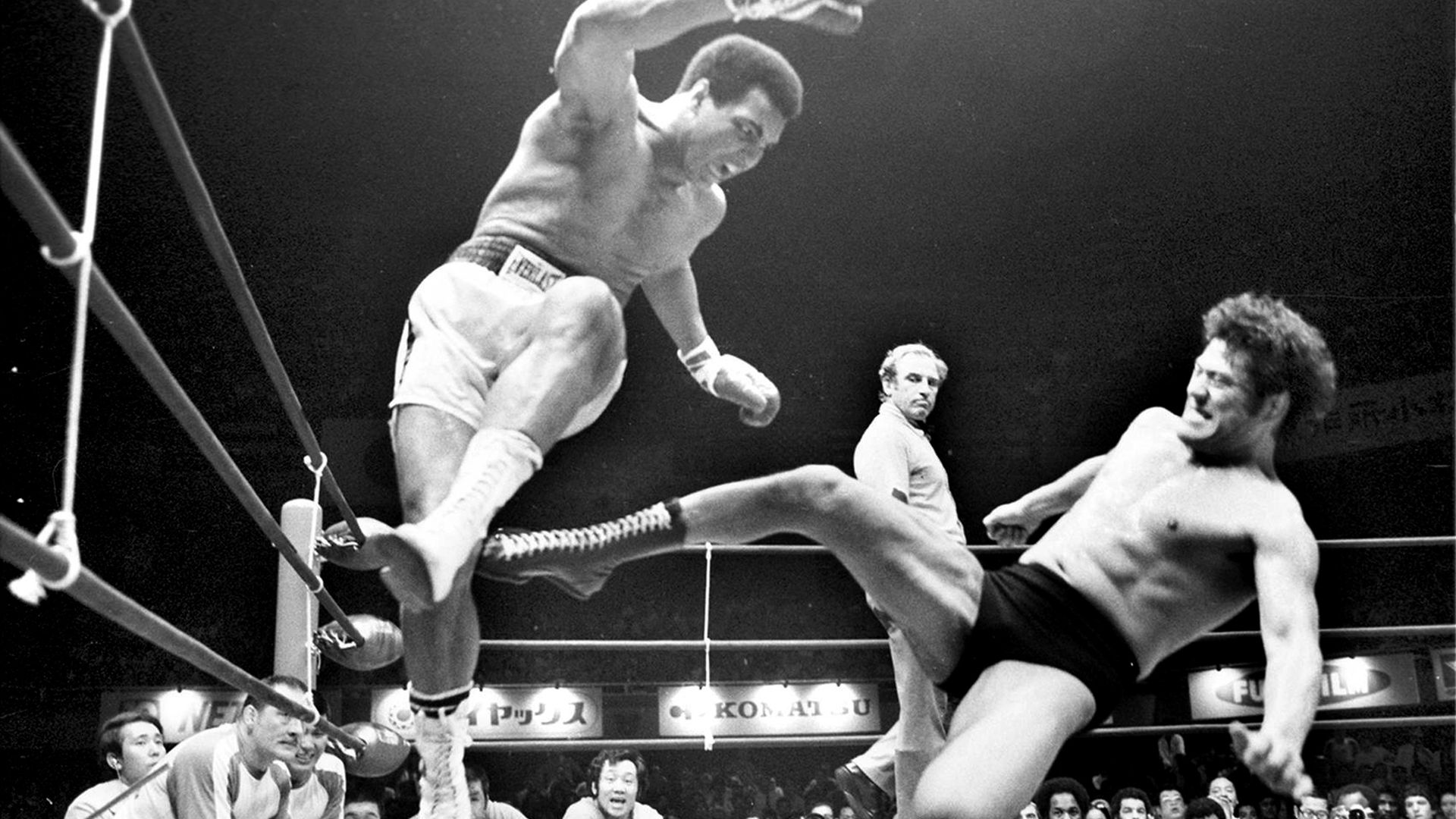

Inoki came out flying, launching himself across the ring feet first. Ali dodged. Inoki tried again and Ali dodged again. Then the wrestler set upon a new tactic which defined the contest. He stayed on the floor on his back, crawling around like an up turned crab and aiming kicks at Ali’s legs. He spent just 14 seconds of the opening three-minute round on his feet.

Ali spent most of the fight trying to avoid being kicked and taunting Inoki to stand up and “fight like a man”. He didn’t throw a punch until the seventh round and didn’t connect until the tenth, in all he threw just six punches. By contrast, Inoki connected with 107 kicks. None of them caused serious damage on their own but cumulatively they had huge impact, not least because Inoki was wearing hard leather boots with metal rivets on the end. By the third round a deep cut had opened up on Ali’s left knee.

The highlight – if it can be called that – came in the sixth round, when Ali tried to grab his opponent’s left leg only to be felled when Inoki grabbed Ali’s foot and swept him over. The wrestler then managed to hold Ali down before hitting him in the face with his elbow. The referee pulled the fighters apart and Inoki was deducted a point.

In the end the fight was scored 74-74, although Inoki had three points deducted in total for dubious infractions. The result meant no one lost face. Inoki was able to claim he would have won but for the penalties and Ali was able to claim his opponent had cheated. However, the crowd inside the Budokan Arena were clear who the losers were: them. Hurling rubbish at the fighters, they made their feelings clear, shouting “Money Back! Money Back!”

Despite the criticism, and the fans’ feeling that they had been cheated, the fighters both sustained serious injuries. Inoki’s right leg, which he used for the majority of the kicks, was fractured. Ali’s left leg, which received most of Inoki’s kicks, was seriously wounded developing infections and blood clots. He was scheduled to take part in exhibition fights in South Korea and the Philippines, but Pacheco told him to cancel, urging him to seek medical treatment instead.

Ali ignored his doctor’s advice and fought the exhibition bouts. On his return to the USA he required an extended stay of hospitalisation. The wound to his left leg become so bad that amputation was seriously considered. He was placed on blood thinning medication to prevent the clots from spreading to his brain, heart or lungs, something that could have proved fatal.

Pacheco would soon quit his role as Ali’s doctor in frustration and although Ali recovered, his movement, which had once allowed him to ‘float like a butterfly’ and upon which much of his early success was built, was restricted for the rest of his career. The fight exacerbated the decline that had already begun. He would never knock out an opponent again.

The pair met in the ring again in 1998, following Inoki’s final fight before retirement. They embraced with Ali hailing their friendship. By this time, Inoki had become a successful politician and businessman selling products such as branded water and condoms. He was as famous in Japan as Ali was in America and like his former opponent had successfully negotiated with Saddam Hussein for the release of hostages during the Gulf War.

Their fight is now a largely forgotten footnote to Ali’s career and for many of those who do remember it, it’s seen as a highly embarrassing affair because the convoluted rules made it such a farcical spectacle.

Yet, it’s still the most-viewed mixed martial arts (MMA) fight of all time and it helped inspire the first generation of MMA fighters in the USA and Japan. As strange as it may seem, not only does Ali stand over the boxing world like a Colossus he was also, along with Inoki, one of the early practitioners of MMA.

Five cross discipline bouts

John L Sullivan, the first heavyweight champion of the gloved boxing era and the last heavyweight champion of the bareknuckle era, fought William Muldoon the world Greco-Roman champion in 1889. Two years earlier, Muldoon had trained Sullivan for his 75-round epic against Jake Kilrain, however when they met in the ring, it took him just two minutes to slam Sullivan to the floor and claim victory.

The first televised mixed discipline fight took place in 1963 between Gene LeBell, known as the ‘Godfather of Grappling’, and boxer Milo Savage. Staged in Salt Lake City, the fight was a close affair. Savage had clearly trained in judo in a bid to counter his opponent’s technique. However, in the fourth round LeBell gained the upper hand and choked out Savage. He drew on the experience 13 years later when he refereed the Ali-Inoki fight.

On the day Ali fought Inoki in 1976, fans at the Shea Stadium also got to see boxer Chuck Wepner fight wrestler Andre the Giant. Wepner had lost to Ali by a last-round knockout the previous year, a fight which inspired Sylvester Stallone to write Rocky. His three-round defeat to Andre also inspired the charity bout between Rocky and wrestler Thunderlips, played by Hulk Hogan, in Rocky III.

In November 1993, lightweight boxer Art Jimmerson took on Royce Gracie, in the first round of the first Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). MMA was not what it would become with most of the competitors proficient in just one discipline and inexperienced at fighting people with different skills. There were three basic rules: no biting, no eye gouging, and no groin shots. Jimmerson was out of his depth and wore just one glove, to ensure the referee could see him tap out, which he did very quickly. Royce Gracie, who practiced Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, went on to be crowned champion.

In 2017 reigning UFC lightweight champion, Conor McGregor stepped out of the octagon and into a boxing ring in Nevada to take on undefeated former boxing champion Floyd Mayweather Jr in a 12-round boxing match. Mayweather began to take control in the ninth round and was declared the winner in the tenth on a technical knockout, maintaining his undefeated record. The fight recorded the second highest pay-per-view TV audience in US history, earning the fighters more than $100m each and re-enforcing the fascination with fights between practitioners of different disciplines.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37