Decades before the existential threat of Brexit, acts including Kraftwerk decided inclusion was far more important than excommunication.

If there was anyone who really understood the magnitude of a ‘European’ music, it was Kraftwerk. Decades before the existential threat of Brexit, years before the brutal reality of Populism, and a generation before the Union Jack was starting to be sequestered because of its toxicity, the Düsseldorf four-piece had decided that inclusion was more important than excommunication.

Their masterpiece in this respect was Europe Endless, the beautiful first track on their 1977 album Trans-Europe Express, a song that carefully expressed the apparently inexhaustible delights of the continent: parks, hotels and palaces, promenades and avenues, real life and postcard views.

The robotic nature of the music was the most important aspect of the song, though, as at the time the band were keen to move themselves away from their German heritage towards a new sense of European identity.

It has been described as an electronic pastoral, “painting a picture of a unified, borderless Europe”. Since then, walls have come down, walls have come up, although Europe Endless exists in a state completely separate from all this.

There had been many ahead of them, and even more who came in their wake, yet it was Kraftwerk who made themselves seem truly European.

For some, the mock heroics of Ultravox’s Vienna was all they needed to hear in order to be transported to a mythical Central European cake shop, while for others it was Lou Reed’s Berlin, although for the generation of night owls who came to the fore in the late 1970s and early 1980s it was probably Roxy Music’s A Song For Europe, the anguished warble of a continental sophisticate, wondering where his true love has gone, while possibly trying to attract the attention of his waiter.

The very idea of continental Europe is one that evokes melancholy, a wistful longing for a solitary existence, wandering the city streets while pulling on an unfiltered cigarette. In this instance the most fulfilling record is probably David Bowie’s nostalgic walking tour, Where Are We Now?, an uncharacteristic look over the shoulder at a time and a place long gone, that period in the 1970s when Bowie was inadvertently inspiring a generation he had already culturally assaulted half a decade earlier.

Bowie, in all his wondrous shapes, was – along with Bryan Ferry – one of the few entertainers of the 1970s who celebrated Europe for its promise of escape as well as its place in history. At the time, when music vaulted you around the world, it either dropped you in the bucolic British countryside, or it swept you along the coastal roads of Southern California.

The electronic music which emerged from mainland Europe at the end of the 1970s not only celebrated its provenance, but it also – fundamentally – sounded different.

You could listen to it in one way and feel it was cold and dispassionate and codified, or you could let yourself be swayed by the smell of Gitanes and Cafe Creme, and allow yourself to drift across the rooftops all the way to the Caucasus.

Europe’s grand design was actually rather easy to sketch, which is why so many bands of the New Romantic period were determined to pull up the collars of their raincoats and look forlorn.

If you needed an example of a song that had had all the meaning sucked out of it then all you had to do was listen to Japan’s European Son (which sounds like a Duran Duran b-side even though it predates it by at least two years).

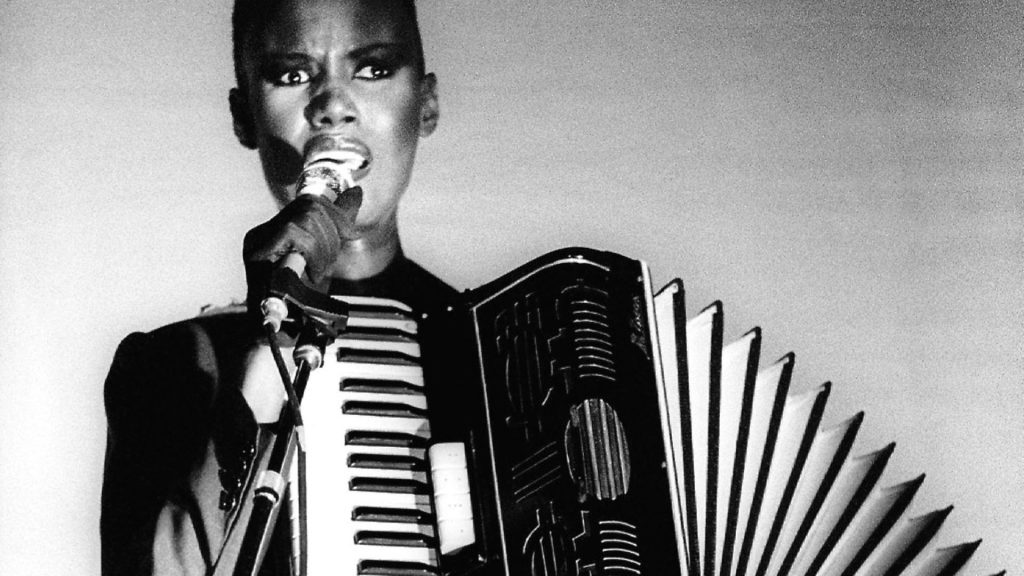

There is one record from the period in particular that managed to escape the genre, creating something very special in the process. Under Chris Blackwell’s direction, in 1981 Grace Jones recorded a reworked version of the Argentinian composer Astor Piazzolla’s Libertango as I’ve Seen That Face Before (Libertango), with new lyrics written by Jones herself and Barry Reynolds.

Driven by Sky and Robbie, and arranged by Blackwell and Alex Sadkin, it conjures something completely original, a mixture of soft reggae, tango and chanson, as Jones recalls a man she sees in every street corner in Paris.

In many ways the song acts as a travelogue, taking us straight to a rainy night in Haussmann Boulevard, but in other, perhaps more sinister ways, Jones acts as a cipher, an androgynous one at that. All in all it was a heady mix, one that perhaps had more of an effect on the culture than the rather lumpen Sweet Dreams, the Eurythmics’ own attempt at transgression with a jet-set bent.

In helping themselves to a particular part of history, namely the romantic and largely fictitious idea of a benign post-war Europe – from the nightclubs of Berlin and the cafes of Amsterdam to the airports of Scandinavia or the railway stations of Burgenland – the post-punk miserabilists and the synth-pop darlings of the period were clumsily putting stakes in the ground, or rather plotting a meaningless journey on a pinboard.

Some simply celebrated their internationalism, with a casual belief in the redemptive properties of global pop. So in the same way that Sister Sledge (courtesy of Nile Rodgers and Bernard Fowler) were espousing the liberating qualities of Halston, Gucci and Fiorucci, so Robin Scott’s M were eulogising the giddy delights of “New York, London, Paris, Munich,” everybody talk about Pop Musik! Escape rather than endurance, fantasy instead of reality.

By 1985 though, this illusion was becoming something of a reality, in the way in which the New Pop of the period was being mediated, as this coloratura was no longer ironic. When, in 1980, the Human League released their Travelogue album, the cover featured a highly evocative photograph of a husky ski trek, in a similar way that a post-punk band may have used a picture postcard as a way of contextualising luxury travel.

As the 1980s reached their mid-point, there had ceased to be anything ironic about the use of, or the purpose of ‘international jet set imagery’. In the worlds of Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran, Wham!, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Madonna, Don Henley, David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, Sting or pretty much anyone else you cared to mention, luxury was a genuine desire.

It was Kraftwerk, though, who truly shackled themselves to the egalitarian European project, albeit somewhat tangentially. Their Mitteleuropean iciness may have become something of a cliché over the years, but their unrelenting dedication to the European cause – a level playing field where one could rendezvous on Champs-Élysées or go to a late night cafe in Vienna – became a blueprint for romantic modernism.

Who cared if you couldn’t afford it, as long as you could feel it. Who cared if you weren’t living the good life, as long as you could dance to it, as long as you could lose yourself in it. Kraftwerk had perfected the illusory power of pop, and that’s where it stayed, as a perfect illusion.

– Dylan Jones is the editor-in-chief of GQ and the author of The Wichita Lineman: Searching In The Sun For The World’s Greatest Unfinished Song, Faber, £10

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37