Forty years ago this summer, the main event at the Moscow Olympics was an almighty clash between sport and politics. MICK O’HARE considers which was the winner.

(Photo credit should read STAFF/AFP via Getty Images) – Credit: AFP via Getty Images

When Allan Wells dipped desperately for the line in the 100 metres final at the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games he wasn’t sure he’d won. He was in lane eight, right on the outside of the track. His nearest rival, Silvio Leonard of Cuba, was far away in lane one. Wells tried to glimpse to the left as they crossed the line almost simultaneously but he couldn’t tell.

His wife and coach Margot, up in the grandstand, peering through her fingers, had to wait agonising seconds before the scoreboard confirmed the result. The Scot had grabbed gold by millimetres, the first Briton to win the event since Harold Abrahams of Chariots of Fire fame in Paris in 1924.

Wells’ winning time of 10.25 seconds would not have ranked him in the year’s top 20, which meant that commentators were suddenly talking about the sprinters who weren’t there: the rapidly emerging Caribbean athletes, the Canadians and West Germans, but most of all the Americans who were expected to dominate.

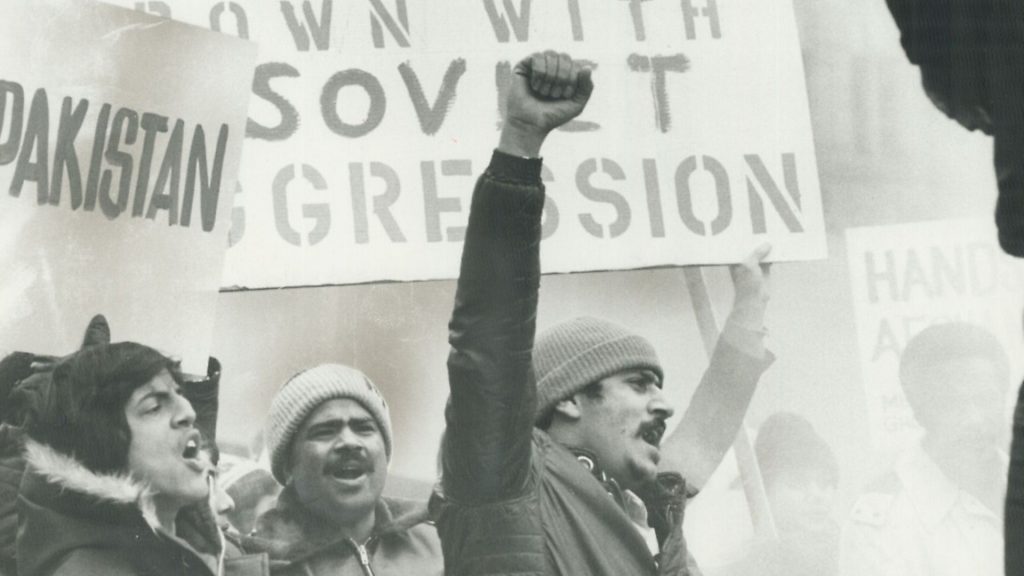

All were missing because the previous December the Soviet Union, host of the 1980 Olympics, had invaded neighbouring Afghanistan.

Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev’s intention was to reinstate the Marxist-Leninist Afghan government of Babrak Karmal under threat from Muslim and anti-communist insurgents.

Naively, in hindsight, the Soviets expected little international condemnation, considering the occupation a personal matter on their own doorstep. But the administration of US president Jimmy Carter was already covertly backing the insurgents throughout 1979 and, with the arrival of 30,000 Soviet troops, another Cold War proxy conflict kicked off.

The notion of a boycott had been rumbling around western capitals for a while, along with talk of other sanctions, but it began to morph into somatic form when prominent Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov was arrested after protesting against the invasion.

His appeal for nations to boycott the games offered the Carter administration an opportunity to win domestic kudos by flexing its muscle on the international stage amid the ongoing debacle of the Iran hostage crisis – a crisis that would go from bad to worse in April when US forces botched a rescue mission to free the 52 Americans held in their embassy in Tehran.

Carter’s foreign policy humiliation was mounting, so in an attempt to recoup waning support in what was a presidential election year (an election he would lose), he announced that if Soviet forces did not withdraw from Afghanistan by February 20, the US would boycott the July games. Congress overwhelmingly backed him but as the Washington Post noted: ‘The Soviet Union has been treating this Olympiad as one of the great events of their modern history,’ and unsurprisingly they refused to accede to the ultimatum. In response Carter, egged on by vice president Walter Mondale and hardline national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, urged allies around the world to follow his lead.

The next few weeks dissolved into a ‘will they? won’t they?’ stand-off between national Olympic committees, individual sports bodies, politicised athletes and their keep-politics-out-of-sport counterparts.

Lord Killanin, the Irish president of the International Olympic Committee, desperately attempted to stave off the boycott. He was fearful for the very future of the games and contended the athletes were being treated as geopolitical pawns. The IOC declared its ‘belief that boycotting a sporting event is an improper way of trying to obtain a political end and that the real victims of any such action are the sportsmen and women’.

But while Killanin was demanding the games go ahead, Carter began to lean heavily on his allies in NATO and elsewhere. He even sent out former world heavyweight champion and Olympic gold medallist boxer Muhammad Ali to tour Africa as his diplomatic envoy. Initially Ali called himself ‘the black Henry Kissinger’ but there was an inauspicious outcome.

He returned with his opinion changed in favour of no boycott – ‘at best, it was ill-conceived; at worst, a diplomatic disaster,’ wrote Ali biographer Thomas Hauser.

In Britain, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher, elected the previous year and promising among other things patriotic resurgence, broadly supported Carter’s stance.

The US president hoped if Britain came on board the rest of western Europe would take note. Sebastian Coe, the world record-holding middle-distance runner whose forthcoming track confrontations against his equally-decorated countryman Steve Ovett were expected to provide Moscow’s pièce de résistance, recounts the athletes’ tension in the months before the games.

‘The uncertainly played on us all,’ he says, ‘and while I understood the anger at the invasion and knew however hard you tried, politics and sport could not be kept apart, it was unfair athletes were being used. It was hypocritical and weak, the politicians should resolve issues themselves.’

British athletes wrote a letter to Thatcher stating: ‘We make it clear we do not support Soviet foreign policy but we are not prepared to preside over the destruction of the Olympic movement.’ She remained unmoved.

In the end parliament voted to boycott, but the British Olympic Committee would not be bowed. Despite vague threats of the government withholding athletes’ passports the committee deemed it was up to individual national sports bodies to choose whether to compete. Luckily for Coe, Ovett and Wells, track and field opted to attend, with only hockey, yachting and equestrian sports staying away.

However, they would be required to compete under the Olympic rather than the Union flag. ‘I think we had public backing,’ says Coe, although he recalls one photograph of departing athletes under the headline ‘Moscow’s latest weapon’.

By now Carter’s faux belligerence – and his arbitrary February deadline – was pasting him into a corner. And when the Winter Olympics, held in the US at Lake Placid, threw up the ‘Miracle on Ice’ – the United States ice hockey team beating the all-conquering Soviet Union and winning gold – public opinion began to turn.

Sport was exciting. Maybe it was better to go to Moscow and whop the Reds on their own soil. US four-time discus gold-medallist Al Oerter concurred: ‘The only way to compete against Moscow is to stuff it down their throats in their own backyard.’

Public sympathy for the athletes was growing. ‘I don’t like having my livelihood wasted,’ said marathon runner Garry Bjorklund. Others were more openly political. Fellow distance runner Carl Hatfield pointed out ‘the Olympics is one of the few events that’s conflict-free. Take that away and you’re further down that continuum that leads to war’.

Because the constitution of the IOC demanded that national committees, not governments, were in charge of sending teams to Olympic games, at one stage it appeared the US Olympic Committee might defy Carter as the British had defied the Thatcher government.

In May, 18 European national Olympic committees jointly announced their intention to defend the ideals of the Olympic movement and declared they had a ‘duty to permit participation in the Games’.

With other western nations following suit, it looked like embarrassment was looming for the president. In the end, after legal attempts to force the US committee to withdraw failed, it took an impassioned speech, appealing to the delegates’ ‘patriotism’ and demanding the athletes not ‘defy the highest elected office in the land’ from William Simon, a former treasury secretary under president Richard Nixon who had served on the Olympic committee, to force USOC members to support the boycott. It was the hollowest of victories. One delegate remarked regretfully that it was ‘either that or being perceived to support the Soviet Union. And I resent that.’ Anti-communist hawk Brzezinski retorted that dissenting athletes were not the ones facing down the tanks of the Soviet aggressors.

Ultimately, while most of the western sporting powerhouses defied Carter, albeit with many competing under the Olympic flag rather their own, some key nations did join the boycott including West Germany, even after chancellor Helmut Schmidt had complained earlier that the US allies should not ‘simply do as they are told’.

His country was followed by Japan, Canada and Argentina while a number of non-US aligned Islamic states joined in protest against the oppression of religion by the Soviet/Afghan government.

So did it work? Carter may have had one eye on the 1976 boycott by mainly African nations of the Montreal games. They objected to the inclusion of New Zealand, whose rugby union squad had toured South Africa in defiance of the informal sporting embargo on playing teams representing the apartheid regime.

While New Zealand were not excluded (hence the boycott) it did raise awareness of widespread opposition to apartheid and eventually – although not until after more protests over a reciprocal incoming South African tour to New Zealand – led to the latter joining the rest of the world in opposing apartheid through sport.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the human rights campaigner, called it ‘the sanction that hurt supporters of apartheid most’.

It might have been this partially successful outcome and the publicity it generated that led Carter to his injudicious position. In some ways he was initially outwardly more successful – 65 nations joined the United States in boycotting Moscow, 36 more than in 1976. However, a central tenet of the IOC is to ‘endeavour to place sport at the service of humanity and thereby to promote peace,’ and Carter banked on nations choosing to ignore this message, seemingly unaware of the significance of each country’s independent national Olympic committee and their adherence to the ideal.

Any patriotic burst from pulling out was almost certain to be short-lived – once the games were under way the public became even more aware that the only group paying a price was the competitors themselves.

A group of American athletes were unsuccessful in suing the government over the damage to their careers but they were successful in sowing resentment of the boycott among the American people. Carter eventually become conscious of this, fearing he might become the man who ‘killed the Olympics’.

Even politicians who outwardly supported the boycott were aware of its drawbacks. Ted Kennedy, the Massachusetts senator, confirmed his support, but added: ‘I want to make clear it is not an effective substitute for foreign policy.’ And that criticism applied as much to the effect the unwelcome pressure Carter brought to bear on his allies had created, as the repercussions or otherwise it had on Soviet foreign policy.

As Coe, who would himself go on to chair the organising committee for the 2012 Olympics in London, notes: ‘In historical terms the boycott must be counted as a failure, but in other ways the Olympic movement is more aware of the need for unity, more determined to resist outside political pressure.’

Nonetheless, the US-led 1980 action would still lead directly to the eastern bloc’s retaliatory boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles games – an unintended legacy of Carter’s actions. ‘Don’t mix sport and politics’ runs the old adage.

Carter, his focus distracted by dwindling prospects of a second term in office, failed to take heed. The Olympics, in any case, proved more resilient than he could have imagined. And even without the participation of 65 nations, 36 world records were set in Moscow.

But of course, the greatest measure of the boycott’s failure was that Carter had hoped to express the opprobrium of the international community, and to force the Soviet Union to withdraw from Afghanistan. Yet it would be 10 years – or two more Olympiads – before they did, leaving behind a ravaged and religiously radicalised nation.

Killanin had this to say of Carter: ‘Whatever the rights and wrongs of Afghanistan, the judgment of one man scrambling for his political life in the American presidential election campaign… turned the Olympic arena into [a] battleground.’ He never forgave the US president.

And for Allan Wells there was vindication. For sceptics who believed he would not have taken gold had the best Americans been in Moscow, the Scot had the perfect riposte. Two weeks after Moscow he accepted the challenge to race them at an invitation meeting in Koblenz. He beat them all.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37