PETER TRUDGILL boldly goes on about one of the most controversial grammatical issues of all.

English forms like to sleep, to run, and to read are technically called infinitives. In the sentence ‘I want to go’, to go is an infinitive. When we want to talk about a particular English verb, we normally cite the infinitival form, as in ‘the verb to go is irregular’. Infinitives can also occur without the to: in ‘You can go’, go is an infinitive.

Some languages do not have infinitives. In Modern Greek ‘you can go’ is thelo na pao, ‘I-want that I-go’. But in languages which do have infinitives, these often consist of a single word: the French for ‘to go’ is aller, the German is gehen, and the Latin is ire. The Scandinavian languages, on the other hand, have two-word infinitives like English: ‘to go’ in Norwegian is å gå.

I have written before about non-existent ‘rules’ of English grammar which have been invented by would-be authorities, such as the particularly daft one stating that you must not end a sentence with a preposition.

Sometimes, we actually know when and where such ‘rules’ were concocted. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a ‘rule’ about infinitives was published in 1803 by John Comley in his English Grammar Made Easy to the Teacher and Pupil.

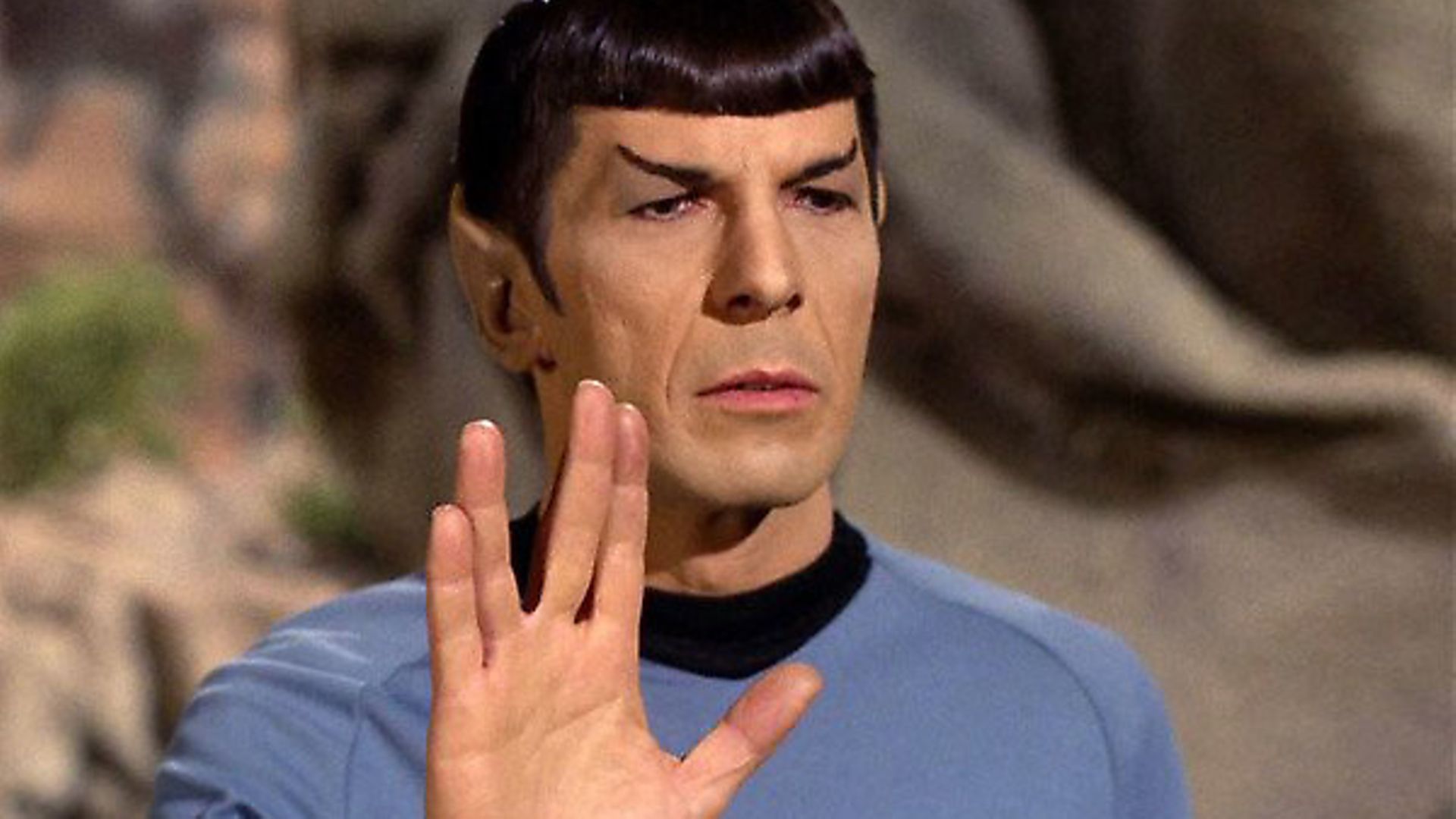

The rule he invented was: ‘an adverb should not be placed between a verb of the infinitive mood and the preposition to which governs it’. This is where many people got the idea from that it is wrong to ‘split’ an infinitive, as in ‘to boldly go where no man has gone before’, as was said of the Starship Enterprise in Star Trek.

It is not clear why this American writer came to think that way about infinitives. Perhaps the fact that infinitives are single, unsplittable words in Latin had something to do with it – another example of a misguided attempt to impose Latin grammar on English.

It is no surprise, though, to learn that he was an American: a majority of Americans are descended from people who were not native speakers of English, and there has always been a stronger tendency in the USA for people to worry about speaking and writing ‘correctly’ than there ever has been here.

This rule became popular with those who derive pleasure from giving instructions to other people about how they should speak their own language. But there is really no need for the rest of us to be concerned: the ‘rule’ is complete nonsense, and we can ignore it, just as the Norwegians do – they have never even heard of it, because no one ever invented a similar rule for Norwegian.

The Norwegian for ‘to boldly go where no man has gone before’ is å modig gå der ingen har gått før, where å modig gå is literally ‘to boldly go’.

In his book Mind the Gaffe, Professor Larry Trask – it is only fair to point out he was American – very wisely observed that it is the split infinitive which makes the meaning clear in a sentence like ‘She decided to gradually get rid of the teddy bears she had collected’.

This is the best way of indicating elegantly and unambiguously that the decision was to dispose of the bears gradually over time. No other word order works as well. If you ‘un-split’ the infinitive and write ‘She decided gradually to get rid of the teddy bears’, that could be interpreted as meaning that it was the decision which was gradual. ‘She decided to get rid of the teddy bears she had collected gradually’ could mean that it was the collecting that was gradual; and ‘She decided to get gradually rid of the teddy bears that she had collected’ is very awkward.

Our famous poets and writers have demonstrated over the centuries that there is nothing wrong with using split infinitives. All attempts to completely and utterly remove split infinitives from English are bound to fail.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37