The Tate Modern and three US galleries have postponed a major exhibition of Philip Guston’s work, alarmed at his depictions of the Ku Klux Klan. Claudia Pritchard reports on a raging art controversy.

In November 1970, the American avant-garde composer Morton Feldman went to see his artist friend Philip Guston’s new exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery on East 57th Street in New York. The two were long-standing friends.

Feldman had bought a Guston abstract, Attar, in 1953, but what he saw at the gallery so horrified him that the intimacy ended there and then.

The delicate, complex vertical and horizontal pink-and-grey grids that radiated gently in paintings such as Attar had already given way to more highly coloured and physical abstracts.

“It’s such a beautiful land you created, so how can you leave it?”

Feldman had asked Guston. But this shift only presaged a bigger lurch in a career that, evolving quickly and expansively, still has the power to shock.

For in the mid-1960s, Guston had turned his back on his attractive and successful meshes of pink and grey and gone back to the drawing-board – literally. He drew basic outlines and simple forms hundreds of times, looking not only their clean contours, but also at the shapes formed by the white space around them.

These lines and curves gradually turned into everyday objects – a cup, an umbrella, a nail, a lightbulb; and into parts of the anatomy – a bean-shaped head, giant hand, knobbly knees.

Finally, some of these coalesced into figures – among them banal and hooded acolytes of the Ku Klux Klan.

“Guston’s 1970 Marlborough exhibition threw the gauntlet down in no uncertain terms,” says Robert Storr, an authority on the artist, whose new book, Philip Guston: A Life in Painting would have coincided with a major retrospective shown over two years at four of the world’s leading galleries in turn.

But Guston can still cause outrage, 40 years after his death. The exhibition has been postponed until 2024, in the United States by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and, in Britain, by Tate Modern.

A joint statement ascribed the decision to pull the show for four years to “the racial justice movement that started in the US”.

But many believe there has never been a more appropriate moment to revisit work that is visceral in its condemnation of racial violence.

“As art museums, we are expected to show difficult art and to support artists.

By cancelling or delaying, we abandon this responsibility,” says Mark Godfrey, who was due to curate the Tate show. He was suspended for his comments.

Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, reacted similarly: “My father dared to unveil white culpability… our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood, when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles.

As poor Jewish immigrants, his family fled extermination in Ukraine.

He understood what hatred was. It was the subject of his earliest works.”

Born Phillip Goldstein in June 1913, Philip was the youngest of seven children born in Montreal to Lieb Goldstein, a blacksmith, and his wife Rachel, who had emigrated from Odessa.

Unable to support his family, Lieb worked on the railways, until the harsh winter drove the family to Los Angeles, where he collected junk and refuse.

There is something of that trade’s abandoned and disconnected objects in his son’s later work.

Overwhelmed by a sense that he had failed to give his family a better life, Lieb hanged himself in the back porch in 1923, and was found by the 10-year-old boy.

A second traumatic experience would further inform the artist’s work. His adored older brother Nat lost both legs, and then after gangrene set in, his life when he was crushed by a rolling car.

The legs that fold and pile in pictures such as Monument (1976), one of the stars of the Tate collection, are discomforting enough without knowing of his family trauma.

While many parents would have steered their child away from comic books, Rachel encouraged Philip when he took up drawing, inspired by the “funny papers” – the Sunday titles’ cartoon supplement – above all by characters Mutt and Jeff, and Krazy Kat.

He took a correspondence course with the Cleveland School of Cartooning, won a prize and had his entry published in the Los Angeles Times.

Forty years later, he would return to the immediacy of commonplace images and the swinging lightbulb by which he drew as a teenager.

But his route back to those elemental images was circuitous. It began at Los Angeles’ Manual Arts High School, where classmates included Jackson Pollock, and where he excelled in neo-classical drawing.

His early influences included the Italian metaphysical artist Giorgio de Chirico, with his proto-surrealist detached objects and spaces.

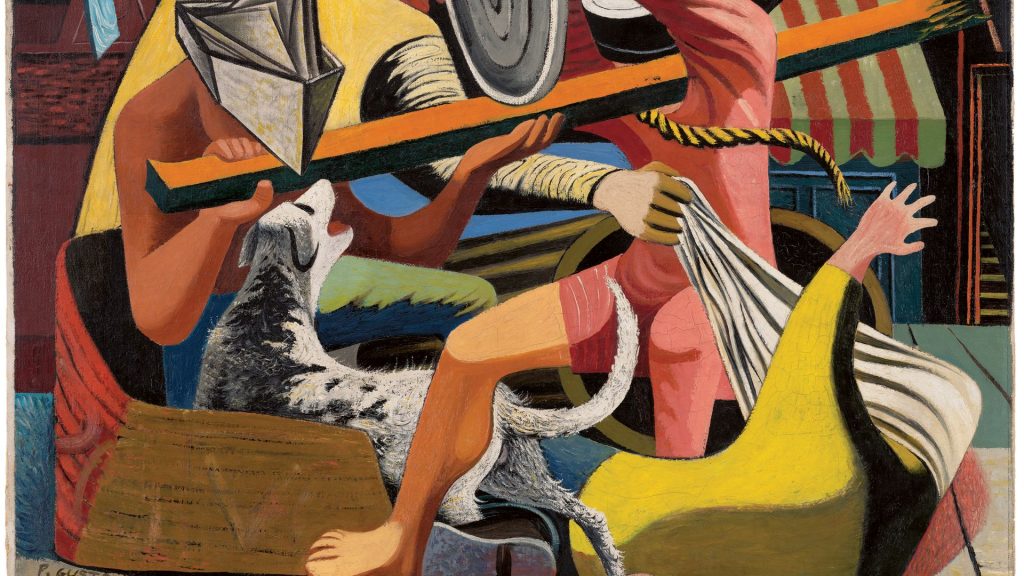

But he revered too the monumental figures and mathematical composition of the 15th century Italian Renaissance painters, above all, Piero della Francesca (a lecture on him is reproduced in Storr’s book). And he also admired the bravura brushwork of Frans Hals. His play-fighting boys in Gladiators (1940) tussle with improvised helmets and weapons, their crisscrossing reminiscent of Uccello’s sea of soldiers in his mid-15th century Battle of San Romano.

A beneficiary of Franklin D Roosevelt’s imaginative depression-era Federal Art Project job-creation scheme, Guston, who had by now worked with others on murals in Mexico, created in scenes such as Gladiators (1940) figures engaged in conflict, creative or community activity.

After the Second World War he caught the wave that propelled the avant-garde from Europe to the US with large-scale abstracts whose grid-like structure centres on knots of intense colour.

As the knots loosened in the late 1950s in works such as The Return (1956-58), the tone thickened and darkened – Guston referred to his palette as “coloured dirt” – until only a sinister black head-like lump floated suggestively.

It was at this point that Guston returned to his drawing roots and built a new visual language.

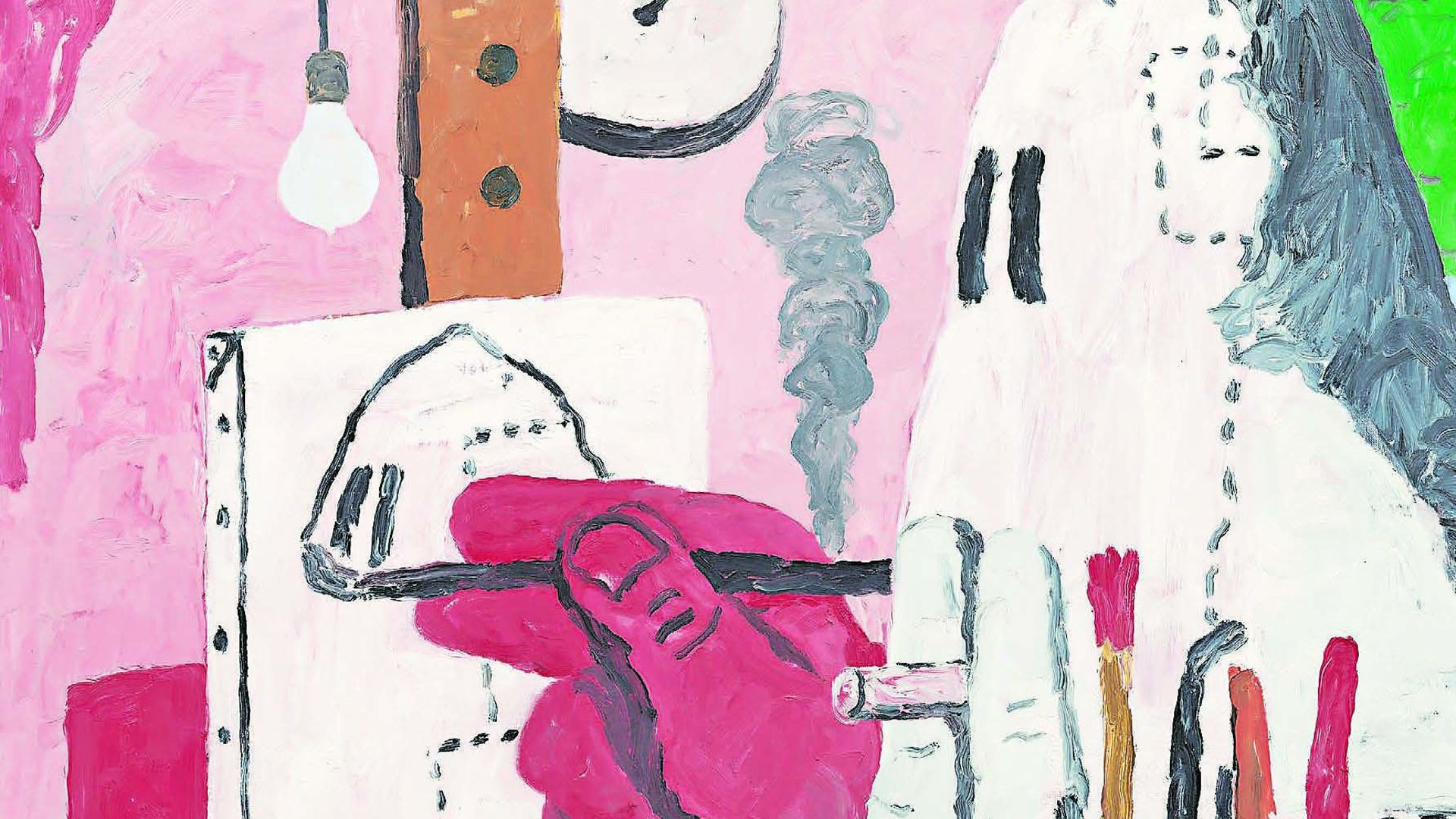

With his now newly controversial KKK pictures, over five years he ridiculed the banality of evil, his pathetic little men wagging stumpy fingers from their clown cars, or peeping through hoods with sight but no vision. In The Studio (1969) he self-critically conflates himself and a Klansmen.

As the KKK faded from the pictures, new characters emerge, represented only by feet and legs, single eyes, scrawny arms. Occasionally the blond head of wife Musa McKim pops over a horizon.

But there is little domestic bliss in Guston’s work. More, the sheer physical effort and black comedy of life itself.

In June 1980 the artist died suddenly at the dinner table of friends, his doctor and wife – the parents of chef Ruth Rogers.

Posthumous exhibitions ran into dozens. In every one of the intervening 40 years there has always been at least one Guston show, often several.

That Washington, Boston, Houston and London should take fright now would surely have made the artist exclaim, as he would on viewing his own work anew: “My God, did I do that?”

- Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting, by Robert Storr is published by Laurence King at £60

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37