In the 1970s two New York venues were at the beating heart of a culture that spread around the world. Garth Cartwright talks to the photographer who captured the scene

New York City in the early-1970s was dirty, decrepit, violent and hugely creative. Back then the Big Apple served as the epicentre of US arts – with Andy Warhol as its peroxide wig prince – and letters (Norman Mailer as the two-fisted magus of that scene).

At the same time Martin Scorsese was using the neighbourhoods he grew up in as backdrops for some of American cinema’s fiercest films. Oddly, for a city that had been home to so much great jazz and R&B, doo-wop and girl groups (The Ronnettes, The Crystals, The Shangri-Las), its rock scene appeared moribund. The Velvet Underground had long since split and Lou Reed’s solo career was misfiring. The New York Dolls had been the toast of the town but, after two critically praised yet low-selling albums, they disintegrated. Only Kiss – yes, the wretched Gene Simmons-led panto’ metal band – had achieved any degree of success.

Yet two small rock clubs, Max’s Kansas City and CBGB, were throbbing to the sound of fearless young bands.

Max’s first opened in the mid-1960s, serving as home for both Warhol’s crowd and many bands (The Velvets played their final gigs with Reed there), before closing in late-1974. Reopening in 1975, Max’s now focused on booking the new bands then playing CBGB.

Hilly Kristal opened CBGB in 1973 and, by 1975, his club was the cognoscenti’s choice. When forced to close in October 2006, CBGB was an American institution and the world’s most famous rock club. Kristal would die of cancer a year later and has since been played by Alan Rickman in 2013 biopic CBGB (don’t bother, its dire).

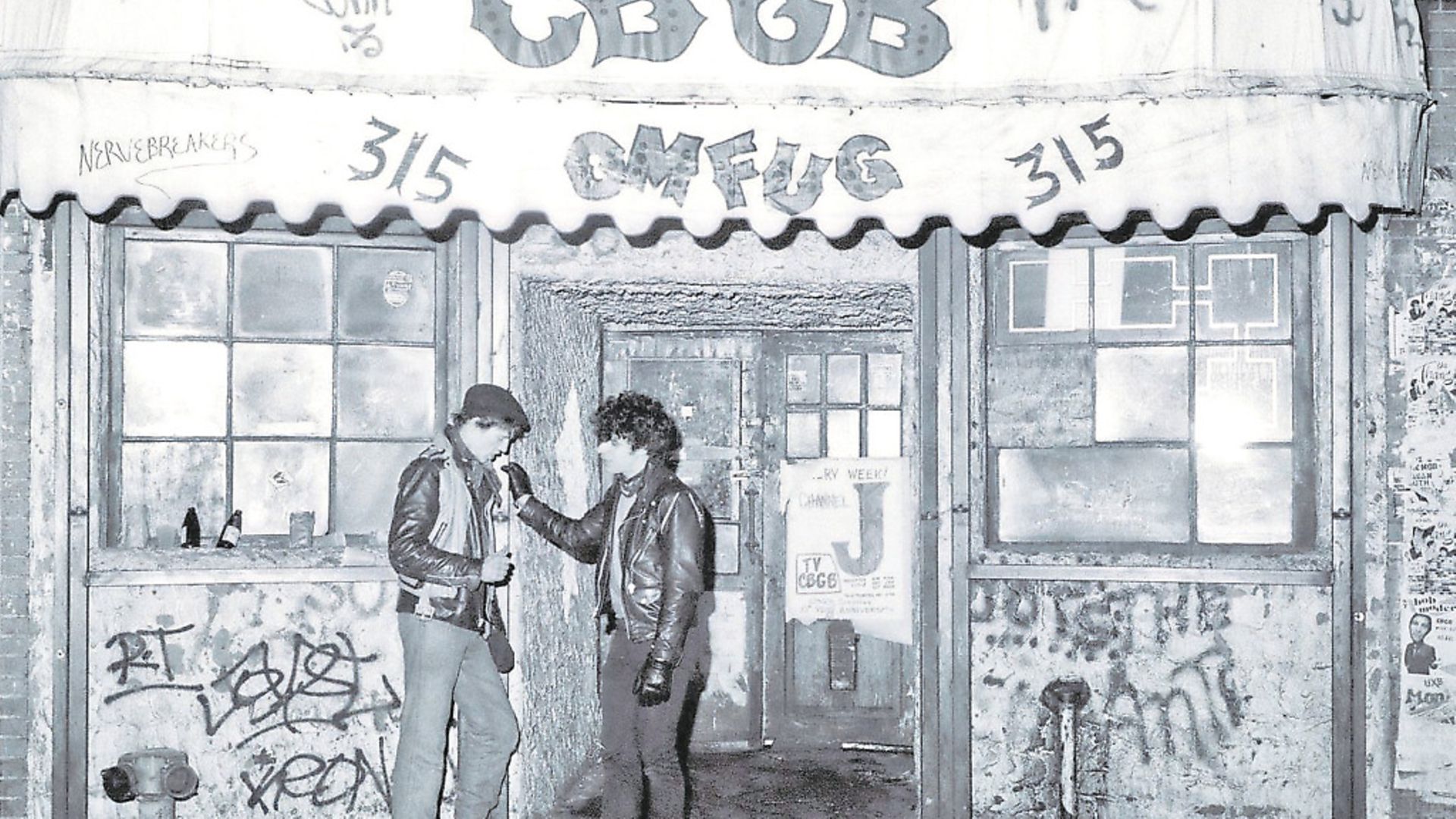

New York to the core, Kristal moved from being a jobbing musician to working in jazz clubs to opening his own bar, Hilly’s, in 1966. He lost this in 1973 due to complaints about noise, shifting to 315 Bowery, off Bleecker Street, and taking over a dive bar, renaming it CBGB & OMFUG.

The club’s full name stands for ‘country bluegrass blues & other music for uplifting gormandizers’. Both by location – the Bowery was NYC’s Skid Row, home to homeless alcoholics and vagrants – and music format, it appeared doomed.

In early-1974 Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell asked Hilly if their fledgling band, Television, could play CBGB. Hilly gave Television a Sunday night residency and the youths built CBGB’s stage.

On it, American rock began to reinvent itself. Manhattan had few venues that regularly offered new bands the opportunity to play and Kristal’s openness to bands playing original material – no matter how raw or inept – ensured CBGB served as an incubator.

Amongst the fledgling rockers playing CBGB were Patti Smith, confrontational electronic duo Suicide, transsexual rocker Wayne County and The Ramones, who performed their first ever gigs here. The Heartbreakers, Mink De Ville, Talking Heads and Blondie all followed.

US magazines Rock Scene, New York Rocker and Creem began championing ‘the Max’s and CBGB’s scene’ and, when Patti Smith released her debut album Horses in November 1975, the promise crystallised.

Malcolm McLaren briefly based himself in NYC in 1975 as he tried to hold the New York Dolls together. He failed at this but used his time wisely, studying the bands playing CBGB and Max’s.

Back home he set about employing the Bowery aesthetic as manager of a group of London teenagers calling themselves the Sex Pistols.

In 1976, a Live At CBGB’s double album was released showcasing eight bands. Meanwhile, Television and the Ramones released debut albums to critical acclaim, if little commercial impact. ‘Punk rock’ became a media byword: while in Britain there was a certain uniformity, almost all the CBGB’s bands created highly assured and very individual music.

By 1979 both Blondie and Talking Heads would be enjoying global stardom while Patti Smith, Television, The Ramones, Mink DeVille and others came to command iconic status.

The original CBGB bands moved on but Kristal stayed put, continuing to champion rock’s noisy edge: he and his club developed into a much loved emblem of NYC’s abrasive energies (Kristal opened a CBGB’s store to sell branded merchandise). Meanwhile Max’s closed in 1981, its founder Mickey Ruskin dying in 1983.

I interviewed Kristal in 2002 when he visited London to promote the CD compilation, CBGB’s and the Birth of US Punk, and he happily admitted initially feeling both Television and The Ramones were ‘dreadful’. Was he proud of his achievements? Certainly, but prouder of how the CBGB bands had gone on to influence others. Patti Smith, he noted, kicked open the door for women in rock.

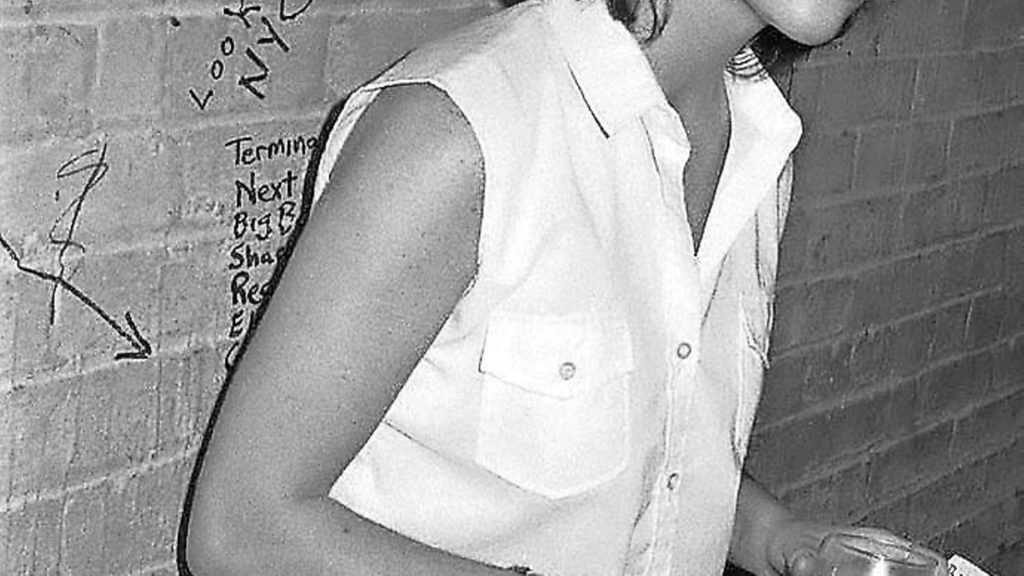

Now there’s When Midnight Comes Around, a book of Gary Green’s photographs documenting the musicians, workers, audiences and cityscape surrounding CBGB and Max’s in the mid-1970s.

The images are in black and white, and raw as a wound. Many are portraits and its remarkable to study Green’s subjects, all so fresh and unguarded. The likes of Joey Ramone and Johnny Thunders are long dead while Debbie Harry and Richard Hell, both still with us, are captured with their youthful beauty intact.

Andy Warhol and Lou Reed both appear – one shot has them together in the audience – alongside images of Tom Waits and Joe Jackson, both smooth skinned musical visionaries.

Looking at When Midnight Comes Around I’m reminded of how grungy rock venues were: cigarettes and graffiti predominate while every surface appears filthy. And the atmosphere is electric, charged.

The sounds shaped in these clubs helped change rock music, art, fashion. And as the world changed so did NYC: today the Bowery is home to millionaires and the raw and the poor, the weird and the marginal, have been forced out.

I contacted Green, who now lives in Maine where he’s an associate professor of arts at Colby College, during lockdown. With NYC’s live music venues all shut while the streets were packed with BLM protesters, it seemed an apt time to speak on the US’s foremost city.

‘It really has been the worst period of time I can remember going through in my life,’ notes Green, ‘and I’ve lived through a lot: the trio of assassinations in the ’60s, the Vietnam War, 9/11, the subsequent wars and now Trump and the virus.

‘Maine is not as bad in terms of the virus or riots as we are a very rural state. In terms of protests, they have been totally peaceful here. Many are speaking out, publicly and online for a change in police tactics and an end to divisive and repulsive racism.’

Recalling his halcyon days on the NYC rock scene, Green says, ‘I grew up in the Long Island suburbs, went to college upstate, and moved to New York City in 1976, where I became an aspiring professional photographer. After a while, when I really had a good group of photographs, I took them to the New York Rocker, which began publishing my work and giving me assignments.

‘In those days you could see a set of Vassar Clements or Bill Monroe at the Lone Star Café on lower Fifth Avenue and then easily catch a late set or two at one of the clubs like Max’s or CBGB. There was a lot to like. My main goal throughout was to try to make a good photograph that could stand on its own, celebrity or not.’

Did, I wondered, Green sense then how world-conquering the scene would be?

‘Personally, I thought it was amazing at the time and a lot of the music has proven its integrity and longevity. It had everything going for it – great music, make-up, crazy clothes, sex, drugs – that would make for its popularity in the press.

‘Being young. Meeting some very cool people. Mostly it was the excitement of the new. New York was an amazing place to be in those days. I have so many good memories.’

Considering how grungy the environment looks in Green’s photos I had to ask why he didn’t include a shot of CBGB’s infamous toilets – regularly described as ‘beyond filthy’.

‘I just never cared in those days,’ replies Green. ‘If it was too nice or clean, it wouldn’t have suited the music or the crowds. Also, CBGB was on the Bowery, which was New York’s skid row. The club was right next to the Palace Hotel, a disreputable dump for those without homes.’

Films of the time – Taxi Driver and The Warriors – portray NYC as feral: was it?

‘Taxi Driver is the right comparison. New York was gritty, dirty, and poor in those days. You could be a poor artist and easily survive in those days. The apartment I shared with Sylvain Sylvain [guitarist with the New York Dolls] cost $300 a month for rent and we split that three ways. It didn’t feel dangerous, although when you live in New York City you get a pretty good sense of where you should and shouldn’t be at a given time. The subways were covered completely in graffiti and rarely had air conditioning working in the summer so it smelled and was steaming hot when you made the descent to the trains. Drugs were all over well into the ’80s when I lived on a crack-infested street on the Upper West Side. That felt a little dicey to me but, again, it was cheap even for then.’

Several photos were taken at the Chelsea Hotel, where many a musician, actor and writer would reside while in NYC. Unlike CBGB and Max’s, the Chelsea Hotel still exists (if extensively remodelled).

Green admits that compiling When Midnight Comes Around involved a certain melancholy.

‘What’s so sad about this time is so many people pictured in the book are gone. I remember The Ramones coming to the studio on 31st Street and basically fighting with each other throughout the shoot. I thought that was funny but they seriously didn’t get along. Everybody knows now that Johnny and Joey didn’t even talk after a while because Johnny stole Joey’s girlfriend. Tommy was really the glue and organisation of the group. And now they’re all gone.

‘My best memories of those days are walking downtown with Sylvain, getting coffee or Cuban Chinese food. Sylvain knew so many people in those days, either from the early Dolls days or his sweater-making days with Billy Murcia, the first Dolls drummer, that walking around downtown with him was a totally social event. That and hanging out at Max’s, seeing the Ramones and Blondie and a million other great bands from then, feeling almost like you owned the city when you were out late at night, and most of all making photographs. That was always the goal for me. New York was at the centre of the world in terms of art, music, and culture in general, and I felt so lucky to be there.’

Green is infrequently in NYC these days and rarely encounters those he once photographed more than 40 years ago. He hopes When Midnight Comes Around will reach some of the survivors but has little affection for a city now infamous for producing Donald Trump.

‘New York is way different now but not in a good way. It’s an unaffordable yet still structurally challenged city that is no longer a place where immigrants, artists, and other fresh voices to the culture can afford to live. A great loss, but the world constantly changes and I’m sure it will change again.’

When Midnight Comes Around is published by Stanley/Barker; for more information, visit garygreenphotographs.com

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37