Loathed by Picasso, praised by Matisse, Pierre Bonnard is an artist who split opinion, writes Claudia Pritchard. A major new exhibition of his work shows how he still does.

‘Don’t talk to me about Bonnard,’ protested Picasso around the time of the older artist’s death in 1947. ‘That’s not painting, what he does. He never goes beyond his own sensibility. He doesn’t know how to choose.

‘When Bonnard paints a sky, perhaps he first paints it blue, more or less the way it looks. Then he looks a little longer and sees some mauve in it, so he adds a touch or two of mauve, just to hedge. Then he decides that maybe it’s a little pink too… The result is a potpourri of indecision.’

Harsh words from the man who polished off his own Nude in a Red Armchair in a single day – or liked to give that impression – before tumbling his model into bed. Bonnard, on the other hand, would revisit canvases at up to 25-year intervals, and stayed with the same woman for 50 years.

The art that so irritated Picasso delighted his friend and rival Matisse, who leapt to Bonnard’s defence when he was attacked in print: ‘I have known him all my life, this rare and courageous painter… He made some works of the highest quality and that will endure… He is already accounted one of the greatest painters.’

The explosions of colour and mild-mannered scenes in an important new show at Tate Modern demonstrate vividly all that both infuriated Picasso and won Matisse’s admiration. The first major UK Bonnard show for 20 years, Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory features 80 or so oil paintings, plus revealing preparatory drawings and a number of photographs by and of the artist – some holiday snaps, others compositions that would underpin paintings later.

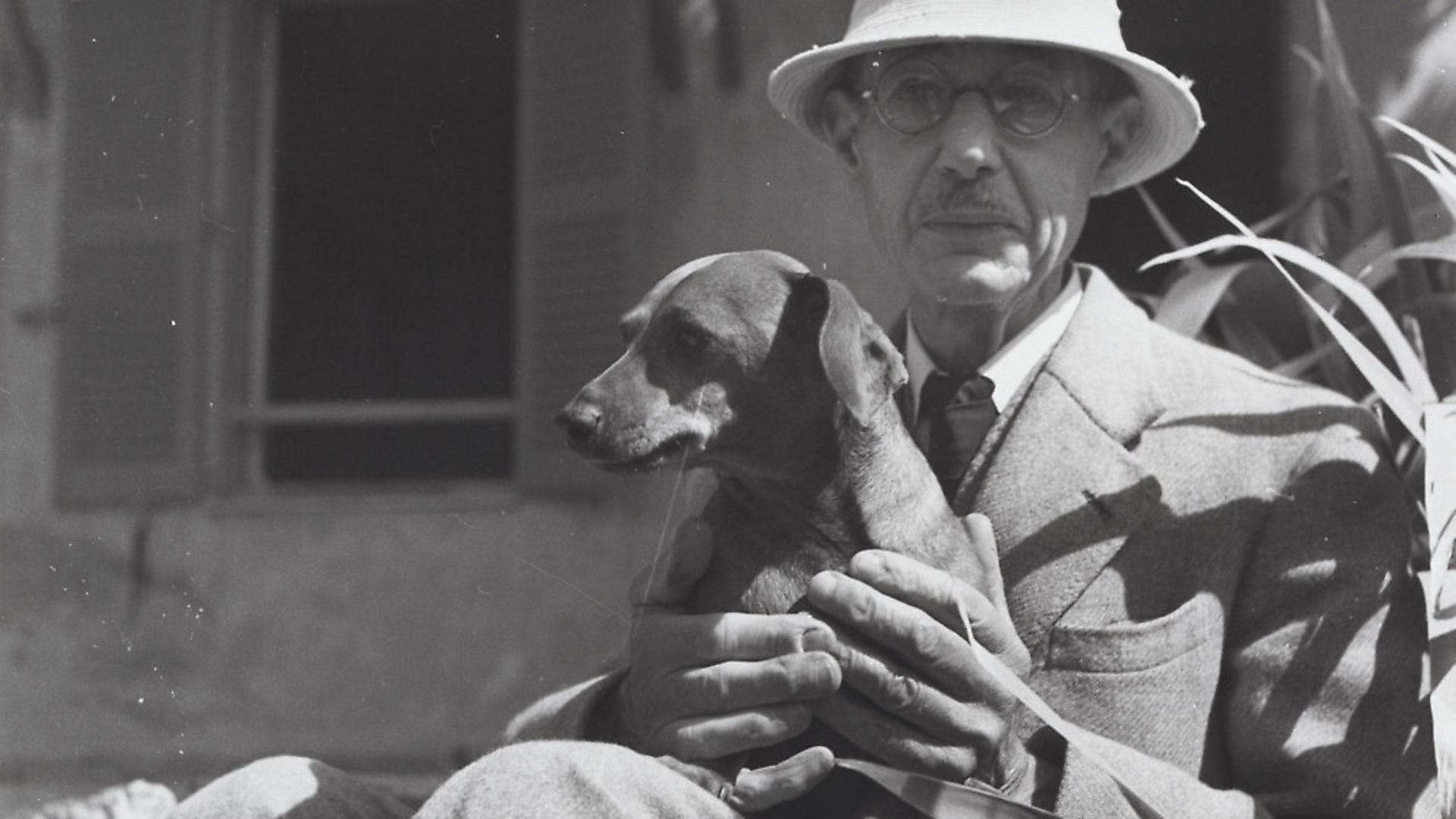

A few minutes of film of boating, taken by the influential dealer and gallerist Aimé Maeght, shows a tentative Bonnard, bespectacled, buttoned up and behatted, bobbing about on the waters. It is a relatively rare excursion out of the world he most often portrays: the home and garden.

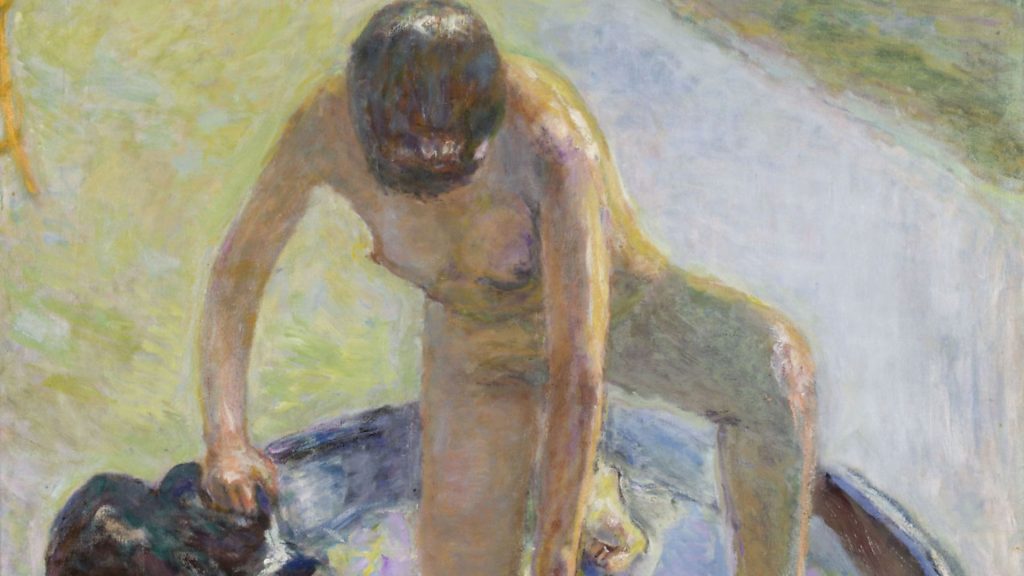

Like Matisse, he revisited the same scene time and time again, but seldom strayed far in either direction beyond the kitchen or bathroom. There are tables and chairs this side of the back door, a profusion of flowers and vegetation on the other; a figure in the bath might be centre stage, or merely an obstacle encountered on the way to a particularly eye-catching wallpaper.

‘The presence of the object… is a hindrance for the painter when he is painting,’ he said, while not going as far as Malevich decades earlier who with his call to arms, ‘Comrades, arise, free yourselves from the tyranny of objects’ rejected the figurative altogether.

Bonnard is not as radical, but with his repeated motifs of diminishing surprise he explores colour for its own sake and crops the image within an inch of its life.Figures are pushed to the edge of the canvas as he experiments with compositions that have their own central magnetism. It is the indigo platter and red checkered cloth that dominate Tate’s own Coffee (1915), and not his squashed-out lover Marthe and half-dog.

The same narrow hound peeps out of several paintings, a black cat winds persuasively in another Tate acquisition, The Bowl of Milk (1919) with its unusual, standing and monumental figure, and kittens pounce on the post-coital bed in the autobiographical Man and Woman (1900). With these pop-up pets there is a playful side to Bonnard, whose interiors are often melancholic where Matisse’s are sumptuous, despite similar props.

There is sleight of hand too: in the several mirror paintings, basic geometry tells us that we are standing where the models should be posing. Compositions are often bisected by a door, window frame or folded screen, allowing several changes of pattern in quick succession. Marthe is submerged for Nude in the Bath (1936), her grey and boneless form lying coolly between rapidly changing and exuberant explorations of tiling and Klimt-like grids of gold.

An admirer of the Japanese artists Hiroshige and Hokusai, he adopted their similarly high viewpoint, creating a vertiginous, birds-eye view of his home, and propelling the viewer into the heart of the painting. Flat surfaces forward, the tableware all but falling at our feet. It was his practice to work on several compositions at once, separating the canvases later.

To suggest something of the immediacy of the studio works, Tate curators have liberated five 1925 paintings from their frames, among them The Window, washed with the white that the artist found challenging. After the firework displays of intense colours, the ghostly whites of In the Bathroom (1940) and The Table (1925, and also unframed here) are haunting.

Marthe was the daughter of a carpenter and midwife who on moving to Paris in 1892 changed her name from Maria Boursin to the more aristocratic Marthe de Méligny. Her long relationship with Bonnard was punctuated by his affairs, notably with the model Renee Monchaty, who appears in some pictures, and who killed herself in 1925, the year that Bonnard and Marthe married.

The many baths were partly medicinal: Marthe suffered from several conditions and seems to have obtained some relief in the water. As she succumbs gradually to her illnesses, her grave form is drained of life.

Bonnard was devastated by her death after a heart attack in 1942, but painted on. The following year he exhibited with Edouard Vuillard, a fellow observer of the daily domestic round. In 1944 he was photographed, as a celebrity, and at the same time as Matisse, by Henri Cartier-Bresson; pictures of him in the studio are in the exhibition.

The fussy brushstrokes and unevenness of the compositions in this huge show may make us occasionally side with Picasso. But illuminating Bonnard’s special vision is his reaction to revisiting the treasures of the Louvre after the Second World War. Looking out on to the busy banks of the river Seine he collared a young staffer. ‘The most beautiful things in museums,’ he said, ‘are the windows.’

Marthe the bathing muse

Bonnard met his wife in 1893. One story has it that he spotted her while she was riding on a horse-drawn tram, became instantly entranced and persuaded her to become his model.

The daughter of a carpenter from near Bourges, in central France, she was working in a shop making artificial flowers for funerals, having moved to Paris to escape her provincial past. In the process, she had changed her name from Maria Boursin to the more refined-sounding Marthe de Méligny – something she did not tell Bonnard until they married in 1925, after more than 30 years of living together.

Just as she told him little about her family, so he, in turn, kept Marthe a secret from his family. Even after their wedding, despite his fame and middle age, Bonnard told few people about their relationship.

For the 49 years from their first meeting to Marthe’s death, she was Bonnard’s principal model. Her fondness for bathing provided him with his best known theme. Art historians remain divided on what precise condition she may have suffered from – tuberculosis, asthma and an obsessive neurosis have all been suggested – but the water apparently offered relief. In Bonnard’s work she often appears in the bathroom, in the bath or stepping out of it. To begin with, these works are charged with eroticism, although as the couple age, this ebbs from the paintings.

Their relationship was punctuated by Bonnard’s occasional infidelity and in 1918 Bonnard met a woman called Renée Monchaty, who he asked to model for him. The two became lovers. However, less than a month after Bonnard married in Marthe in 1925, the jilted Renée killed herself.

After Marthe died of a cardiac arrest, in 1942. Bonnard began to paint landscapes. He died five years later, aged 75.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory runs at Tate Modern, London (tate.org.uk) until 6 May; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (glyptoteket.com), June 6 to September 22; Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna (kunstforumwien.at), October 10 to January 12, 2020

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37