Punk made a noise wherever it erupted. But nowhere was its impact greater than in Troubles-torn Northern Ireland. GARTH CARTWRIGHT reports.

Once upon a time punk rock shook things up. Music, fashion, the media and, most importantly, the very idea of who could be a ‘musician’. For a genre that was often shrill and shouty and sold relatively few units (when compared to disco/heavy metal/country/soul/easy listening/adult oriented rock) punk’s cultural impact was huge.

And nowhere more so than in Northern Ireland.

Punk revitalised rock culture across the world but, in a land torn apart by the Troubles, it served as a lifeline, breathing new life into Northern Irish rock and inspiring a generation.

BP (before punk) Ulster was a dead zone for music and the arts: even the Republic’s showbands had largely stopped visiting after the UVF massacred the Miami Showband in an ambush in July 1975.

Only Irish icons Horslips and Rory Gallagher returned to play annual concerts; the region’s reputation as a combat zone kept almost all others away.

Today its hard to imagine how exciting and life-changing punk was in Northern Ireland, providing a creative outlet, a means of expression, when precious few were on offer.

The bands of Belfast (and beyond) created a scene entirely of their own, without the aid of an existing network of venues and publications. Punk forged alliances that reached across sectarian boundaries and pushed back against an establishment offering little to the region’s youth.

Most impressive was just how striking the Northern Irish punk bands were: the likes of The Outcasts’ You’re A Disease (released May 1978), The Undertones’ Teenage Kicks (September 1978) and Stiff Little Fingers’ Alternative Ulster (February 1979) quickly became anthems.

All sounded seminal then, as they do today, marking Northern Ireland on rock’s map. Not since Van Morrison’s Them burst out of Belfast’s Maritime Hotel in 1964 had Northern Ireland produced rock music so full of desperate yearning. And Them came up in the pre-Troubles era of plenty.

Indeed, commentators would note how while The Sex Pistols and The Clash sang of anarchy and riots the residents of Belfast and Derry experienced such on a daily basis. Here you had the British army on the streets, the IRA and the UDA controlling entire neighbourhoods with paramilitary thugs, gangs of youths battling police and soldiers with stones and being answered with tear gas and rubber bullets, tanks in city centres and helicopters hovering ahead. Bombs, executions, punishment beatings… no wonder the bands sounded so urgent.

Very quickly Belfast’s Stiff Little Fingers and Derry’s The Undertones won critical acclaim and major record deals, both bands shifting to London where they stormed the charts, toured the world and pretty much left the Northern Ireland scene behind (I should note that three of The Undertones have since returned to live in Derry).

But there were other bands who, if they never enjoyed the international success of SLF and The Undertones, rocked hard and represented the raw, underground DIY spirit of the scene.

Both The Outcasts and Rudi possessed great songs if little luck: they issued 45s on Good Vibrations, a tiny record label ran by a maverick named Terri Hooley out of his Belfast record shop (The Undertones’ Teenage Kicks being GV’s most famous release), won airplay from John Peel, rave reviews in the music press (Rudi got signed to The Jam’s Jamming! record label) but neither managed to grab the brass ring that would lift them from Belfast penury to pop success.

Like many a music scene, Northern Irish punk would soon find both interest and inspiration waning and, by the mid-1980s, all the bands had split. Yet recently there has been a real interest in what happened over a few short years in the late-1970s.

Superb 2012 feature film Good Vibrations captured how intense, violent and funny the Northern Irish scene was as seen through Terri Hooley’s eye (he only has one). Its now a winning punk jukebox musical.

Books and features and dissertations have been published and Belfast council has honoured The Harp Bar – where the bands cut their teeth – with a plaque that celebrates Hooley and the noise boys (and they were all, it seems, boys).

London’s Cherry Red Records – long leaders in reissuing niche musical genres – have now documented the scene with a Shellshock Rock box-set. This gathers three (three!) CDs worth of music from that era alongside the DVD of Shellshock Rock, a 52-minute feature documentary from 1978, a book featuring an introductory essay by Stuart Bailie (author of the excellent Trouble Songs, a history of Northern Ireland’s rock scene), copious band biographies by Sean O’Neill (author of It Makes You Want To Spit – the fanzine-style book covering the Belfast punk scene’s heyday) and a treatise from Shellshock’s director, John T. Davis.

Perfect then for someone like me who grew up in suburban New Zealand loving records by The Undertones, Outcasts and SLF but had no connection to the scene.

I’d long been aware of Davis’ film’s existence but there had never previously been a VHS or DVD release.

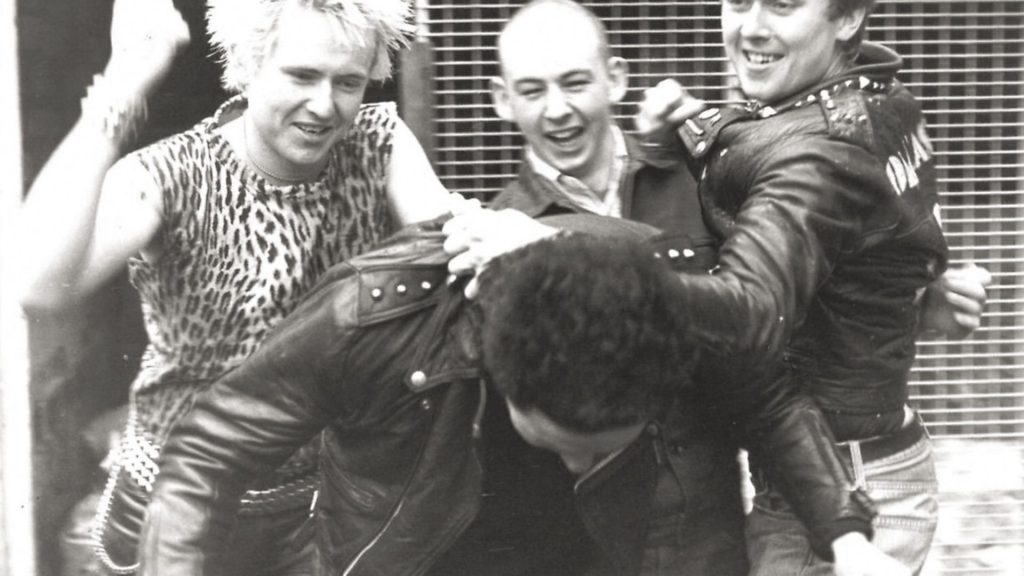

Shellshock Rock proves worth the wait, capturing the Ulster scene as it took raw, beautiful shape. Everyone looks so young (except Hooley, already by then in his thirties), these spotty, pale, thin youths struggling to master their instruments while cranking out desperate, sweaty rock’n’roll.

Also filmed are the fans (literally garrulous kids) alongside shadowy soldiers patrolling the streets and the ordinary people who express bemusement with punk when vox-popped.

Davis, a photojournalist who had befriended D.A. Pennebaker (the American film maker whose Bob Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back pioneered the cinéma vérité music film) applied a similar vérité aesthetic: there’s no narrator, nothing staged, his film is raw and visceral yet lightened by teenage camaraderie and humour. Just like the music.

Shellshock Rock was immediately acclaimed and condemned – in 1979 the Cork Film Festival cancelled its premiere on the day of its screening (deeming it ‘unsuitable’) yet the New York Film & Television Festival awarded it a silver medal. Compared with Don Letts’ The Punk Rock Movie (the London scene in 1977) and Penelope Spheeris’ The Decline of Western Civilization (Los Angeles in 1979/1980), Shellshock Rock stands up as the best of the punk rock doc’ genre.

This is due to Davis possessing a photojournalist’s eye for location and action. Also, the music here is so much more urgent, the London and LA punk scenes being predictably full of poseurs and nihilists: as Hooley noted at the time: ‘When it comes to punk: New York had the haircuts, London had the trousers, but Belfast had the reason.’ Or, as he sometimes says, ‘the songs’. And the best Northern Irish bands had reason and songcraft like few others.

Admittedly, the box-set’s three accompanying CDs (74 tracks!) demonstrate that only a handful of the bands were notable, most being, as in every scene, chancers or uninspired. Still, O’Neill’s copious notes detailing every effort included provide insight into a time when forming a rock band was something many aspired to.

There’s also grim hilarity: showband Candy, having been treading the boards since 1969, decided to jump on the punk bandwagon as Pretty Boy Floyd & the Gems – when Candy fans turned up for a concert and realised their favourite band had hopped genres they literally attacked, hospitalising members… Perhaps not so surprising, violence being a constant in Northern Ireland at the time.

‘Belfast in the ’70s was a very dangerous place,’ says Martin Cowan, guitarist/songwriter in The Outcasts. ‘There was violence everywhere. Wherever we went, because of the way we looked, a lot of guys wanted to pick fights with us and we were always getting stopped and searched by the army and police. But we wanted to take a different path than the norm – I had school friends who got involved in the paramilitaries (while) I had no interest in this and just wanted to get away from this type of life.

‘Music seemed to offer a way out. We called ourselves The Outcasts because we felt like outcasts – most people either hated you or looked at you with disdain. All our early gigs were marked with violence, but gradually we built up a following.’

‘It’s difficult today to convey to people outside Northern Ireland about how it was in the late 1970s/early 1980s in Belfast and other places,’ says Joe Zero (of Victim/The Androids), noting that being a Belfast punk guaranteed no safe space.

‘Violence was always a heartbeat away – you could bump into the wrong people on a dark street any night and the results could be fatal. There were various violent sectarian incidents surrounding punk bands – at an Androids gig at The Harp in May 1978 I had a gun put to my head in the toilets! Also punks were regularly attacked and chased by similar shady characters, especially on their way home from The Harp. At rock gigs before punk in the early 1970s Protestant and Catholic rock fans would attend such gigs but, afterwards, each would head back to their own areas, not really mixing together. With the new punk scene, kids would go to the gigs, mix together, meet the next day, socialise, etc., with no one caring about anyone’s religion, politics, or whatever. Punk was the unifier.’

Martin Cowan agrees. ‘Back then people were segregated and lived in their own communities. The centre of Belfast at night was a ghost town ringed with an iron wall with barbed wire. When bands like us and Rudi started to play The Harp kids from different communities came and starting mixing together. More and more kids came and it became a movement united together because a lot of people hated us.

‘When Terri started to sell punk records and record bands the whole thing grew. He put on three concerts in the Ulster Hall, which held 2,000, in 1979 and ’80. I think these kids provided the first sparks that eventually spread to the wider community.’

Brian Young of Rudi sighs wistfully when I ask him about his memories – Rudi were Belfast’s first punk band, made Good Vibrations’ debut 45 and possessed great potential – but agrees that the local punk scene’s energies were greater than the sum of its bands. ‘Part of the initial appeal of punk, to me at least, was that it was inherently a rejection of everything around you and that had gone before which, over here, included local tribal politics and sectarian divisions, prompting you to challenge and question things you’d been brought up to believe in – and that had a very significant impact and resonance to folk living here in a bitterly divided society.

‘It was certainly more by accident than design too, but as hordes of spiky-topped teens started to cross the religious divide, often for the very first time, and got to know each other, in venues like The Harp, they soon recognised that they had much more in common with each other than they had with the outside world. It’s been said many times before that at places like The Harp most people left their politics/sectarian baggage at the door. And that’s pretty much how I remember it.

‘Self preservation was also a powerful force for unity too as punks were a very visible target for marauding spider men (local thugs) throughout this period. They didn’t care what religion you were or what part of town you came from – the fact that you were one of those nasty punk rockers was more than enough to earn you a good kicking. Even simple things like all walking round to get the last bus home together from The Harp or Pound offered a modicum of protection and helped cement a feeling of unity. At times, it really was as simple as ‘us against them’.’

The violence spread well beyond Belfast. If Records, of Portadown, the first label to record Northern Irish punk, saw its complete stock and masters destroyed by a car bomb while The Undertones, from Derry, were greeted with hostility at home. Their guitarist Damian O’Neill – a 15-year-old schoolboy when they formed in 1976 – laughs when he recalls how his band were considered outliers by town folk.

‘We were the punk scene in Derry. There was no other band like us and we used to get abuse in the street from people who considered us a joke band. Even just having short hair and wearing drainpipe jeans could lead to a kicking.’

All I interviewed agree punk played a role in the Northern Irish peace process.

‘Punk definitely helped bring young people together,’ observes O’Neill, ‘especially in Belfast where more and more punks bands formed and young people who just loved the music didn’t care what religion you were. For us in Derry – being a predominantly Catholic city – it didn’t register that much, although I have to say we did befriend Protestant fans from the east of the city who risked getting their heads kicked in just to cross the river and see us at the Casbah. Unbelievably, these were the first Protestants I ever met.’

‘The punk bands playing the gigs helped open up Belfast’s city centre again after nearly a decade of it being cordoned off and closed each evening,’ says Joe Zero, ‘thus allowing young people to go out and experience music ‘live’ again. And English bands like The Damned, The Clash, The Stranglers, The Fall and others were encouraged to venture across the water to play in Belfast. For me, there is still a positive resonance from that period which is felt to this day. Punk played it’s part in helping to make Northern Ireland a more peaceful place.’

Stiff Little Fingers, The Undertones and The Outcasts all reformed to tour and record new material. They may no longer be angry young men but audiences across the world happily embrace these bands that gave the Troubles a soundtrack: The Outcasts were invited to tour Japan last year and, to their amazement, found Japanese youths who weren’t born last century singing their songs. While the pandemic has currently put everything on hold – The Undertones lost US and UK tours plus Glastonbury festival – it has added fresh resonance to You’re A Disease, Teenage Kicks and Alternative Ulster. The music lives on and the three greatest bands of Northern Irish punk all look forward to new adventures.

‘Back in the day there was a lot of rivalry between the bands,’ reflects Cowan, ‘but now we are all friends and just glad to be alive and able to do it.’

The Shellshock Rock Box-Set is released by Cherry Red Records and is available at HMV, Fopp and many independent record shops as well as online traders

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37