Why is Russia singling the UK out for special treatment? JAMES RODGERS explores the complex relationship between the two countries

When it comes to Vladimir Putin, actions always speak louder than words. That said, the words can be revealing too.

On the website of the Russian Foreign Ministry is a document – available in five languages – grandly titled the ‘Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation’, which outlines the country’s international strategic vision. The text, approved by Putin two years ago, contains a section on Moscow’s hopes for its relations with the rest of Europe. It talks of ‘stepping up mutually beneficial bilateral ties with the Federal Republic of Germany, the French Republic, the Italian Republic, the Kingdom of Spain and other European countries’.

Given Russia’s strained relations with many of these countries, such benign ambitions may sound darkly comic. But what is most revealing about is that the UK is not mentioned in that section. In fact, it does not appear in the entire document – unless you count the general reference to ‘other European countries’.

The implication is clear: the UK does not belong on a list of nations with which Putin will even pay lip service to the idea of seeking good relations. If any doubt was left, Putin has been clear in his actions. The UK may not have been the only country subjected to alleged Kremlin meddling in its democratic processes, but the poisoning of former Russian military officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, in Salisbury – and of former secret service agent Alexander Litvinenko, in London, over a decade earlier – does suggest the UK has been picked out for special treatment.

The reasons for Russian antagonism towards Britain go back further than the murky career history of either of those agents or their involvement with the UK, further, even, than Putin’s rise to power. There is an entrenched view, among many Russians, that the UK is a country which has not treated them well, especially during those times in its history when it was weak.

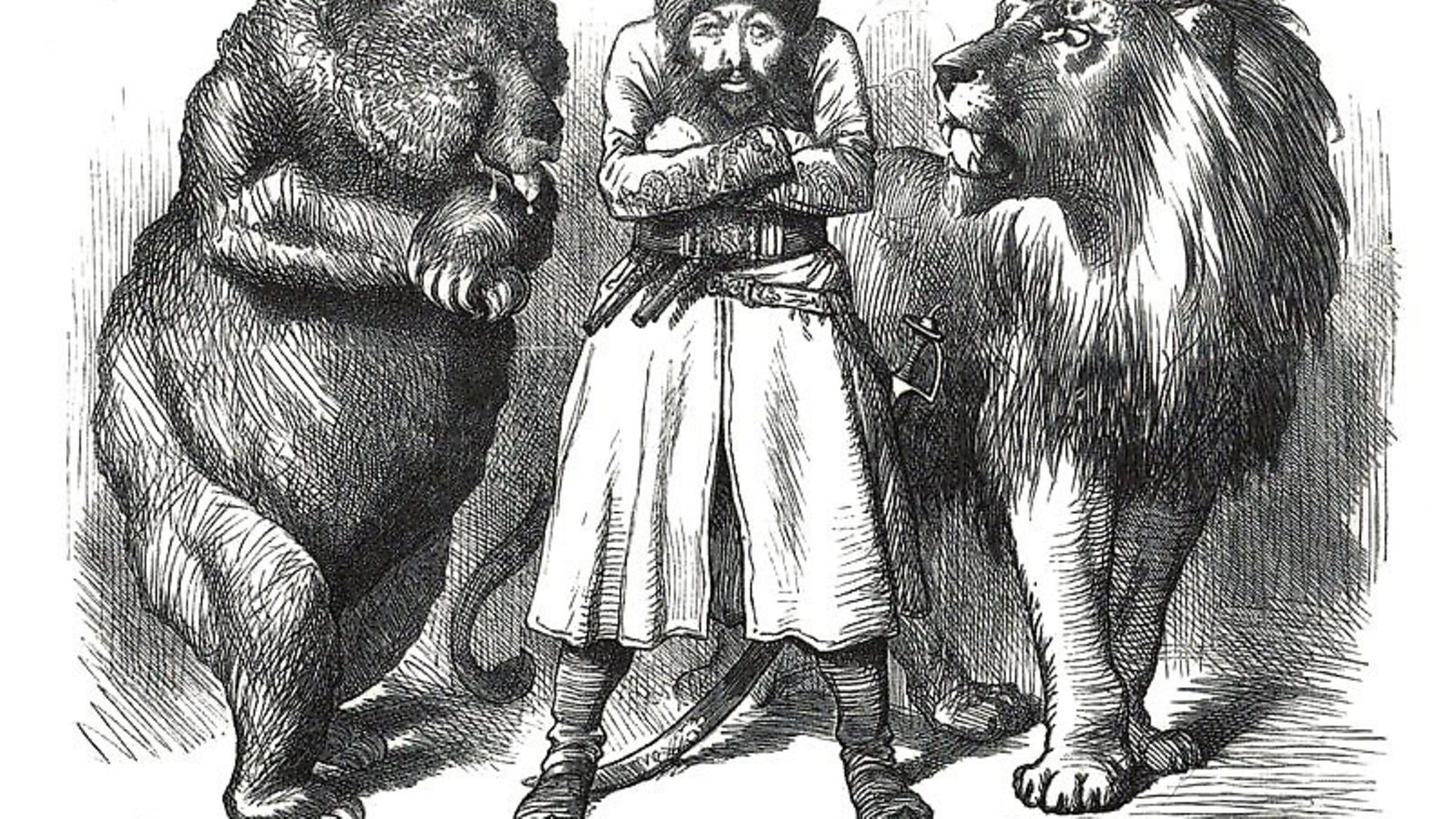

It was not always thus. For a long time, Russia admired Britain. In War and Peace, published in 1869, Tolstoy writes of an Englishman being self-assured because he comes from the best organised state in the world. Even then, though, the seeds of their future rivalry were being sown in the high peaks and plains of central and southern Asia, where British and Russian agents were engaged in what became known as the ‘Great Game’, as the two imperial forces vied for regional supremacy.

It began a long period of – from a Russian perspective at least – underhand British espionage and involvement in encircling and constraining Russian ambition. The next notable chapter came in the aftermath of the October Revolution of 1917, when Britain landed troops in northern Russia to launch a campaign against the Bolshevik regime as it struggled to consolidate its power.

This ill-fated military adventure cast a shadow over relations for the rest of Russia’s predominantly Soviet century. It is still recalled in this century. In his 2005 book, On My Country and the World, the last leader of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, wrote of his belief ‘nothing [had] been forgotten’ since the time when western powers planned that ‘Russia not be regarded as a unitary state’.

Gorbachev will be remembered outside Russia as the Soviet leader who helped to end the Cold War – though many in his own country remember him less favourably as the reformer whose policies led not to restructuring, but to collapse. Whatever your view, he is certainly no rabidly anti-western hawk. His invoking of western intervention in Russia at the end of the First World War shows the length of Russian memories, and the depth of Russian feelings. The subsequent Cold War stand-off, in which Britain played a prominent role, only deepened those feelings.

While Britain is far from unique in having a troubled history with Russia, what is notable is that Moscow perceives the UK to have been a particularly duplicitous adversary, prone to double-crossing and dishonesty, from attempts to thwart Russia’s imperial ambitions during the ‘Great Game’ to offering post-Cold War assurances, not later honoured, that NATO would not eastwards.

Added to this are the very complex developments since the end of the Cold War, which have added to the grievances and made London such a focus of Putin’s attention. In the 1990s, as it staggered away from the wreckage of the Soviet era, Russia was a country where many people found themselves worse off, while a very few made very large amounts of money – not all of it legally.

A sizeable share of that cash made its way to the UK, where it was used to establish a kind of oligarch colony, eventually referred to variously as ‘Londongrad’ or ‘Moscow-on-Thames’. There were plenty among the natives who welcomed the new arrivals: purveyors of luxury goods; top-end estate agents; elite schools seeking fees. When things went wrong, libel lawyers and public relations executives were there to clean up.

That was fine as long as it remained non-political. But episodes such as the granting of asylum to the fugitive oligarch and one-time Putin ally, Boris Berezovsky, and to the Chechen separatist Ahmed Zakayev, infuriated the Kremlin. Britain was seen as providing a haven for enemies of Russia.

This perception led to the relationship hitting a new low in 2006, with the killing in London of Litvinenko, a former officer in Russia’s security service, the FSB. Before his fatal poisoning, he had been working for Berezovsky. Russian officials then – I was a correspondent based in Moscow at the time – saw the presence in London of Berezovsky and others as a political insult to Russia.

Whether or not Litvinenko’s death was ordered from the very top, it sent the message that while Londongrad may have been a pleasant playground, it was not a safe haven. The Kremlin regarded it as an acceptable venue for acts of aggression. Berezovsky himself was found hanged in his ex-wife’s home in Berkshire in 2013: not forgiven in Russia for being among those who had got rich quick in the 1990s; Britain’s offer of sanctuary not forgotten.

Britain is far from alone in being on the receiving end of the Kremlin’s aggression. Just ask the Ukrainian sailors detained after their vessels were seized by Russian forces in the Sea of Azov. But the UK does seem particularly vulnerable to being singled out for special treatment by an increasingly reckless Russia. The extent, or otherwise, of Russian meddling in the 2016 referendum remains deeply contested. What is far less contested is that Brexit – the peeling away of a powerful adversary from its allies – would be a significant strategic success for Putin. The more isolated, introspective and divided the UK becomes, the better for Russia, according to Putin’s simplistic zero-sum calculations.

The Russian president’s overriding foreign policy aim – never mind the platitudes on the foreign office website – is to ensure, by force if necessary, that his country is respected and treated as an equal by powerful nations. By picking on Britain – given our history as an imperial power, current status (still) as one of the world’s leading economies, and permanent member of the UN security council – it looks like Putin is taking on one of the tough guys, and, certainly from a Russian point of view, coming out on top.

In a recent research paper published by the think-tank Chatham House, the former British diplomat Duncan Allen argued, with reference to the attacks carried out on British soil, ‘Russian decision-makers saw the UK as lacking purpose and resolve because its firm rhetoric was not matched by its actions’.

In the wake of the Skripal poisonings, Britain was able to rally its allies in support. There were mass expulsions of Russian diplomats from some 20 countries. Russia is waiting to see if post-Brexit Britain will remain so well supported, and perhaps suspecting that it will not.

Russia’s actions may even suggest that it now feels it can behave towards the UK as it wishes without fear of consequence. It may be just coincidence – lengthy policy documents tend to be months, if not years, in the making – but the foreign policy paper, which saw fit to not even mention Britain, was first published in December 2016, less than six months after the Brexit referendum.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37