The artist’s recent artwork for London Underground didn’t seem to quite hit the mark. But a new exhibition and book shows his energy and love for life remain undimmed

Air travel stopped, and so did the hum of traffic: as humanity fell silent last year, the natural world took centre stage in an exuberant display of life resurgent. As we adjusted to the highs and lows of the ‘new normal’, the progress of that particularly glorious spring provided many people with an absorbing new interest and a respite from the virus, and the news.

On April 1, 2020, David Hockney made public 10 pictures of daffodils and blossoming trees at La Grande Cour, the Normandy farmhouse where he has lived since 2018 in rural isolation with his dog Ruby, and his assistants Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, known as J-P, and Jonathan Wilkinson. “Meanwhile the virus is going mad,” he said, “and many people said my drawings were a great respite from what was going on.”

The public responded with warmth, in contrast to the scorn that has been poured on Hockney’s most recent art work, a design for Piccadilly Circus station, commissioned by the London mayor as part of an art project called #LetsDoLondon.

The wonkily-drawn underground logo, coloured purple and yellow, and with the ‘S’ dropped awkwardly below the preceding letters, has been almost universally ridiculed on social media, where it has been compared unfavourably with the efforts of small children, and the artist accused of trolling Londoners.

Happily, he will have another chance to reconnect with the capital and perhaps restore a slightly bruised reputation with a forthcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy: David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020.

The show features more than 100 new works, including the spring pictures, which– like the London Underground image – are ‘painted’ on an iPad. Together with a series of ink drawings made during the previous year, the iPad pictures also serve as the backdrop to Spring Cannot Be Cancelled, a new book based on conversations and correspondence between Hockney and his friend and collaborator, the art critic Martin Gayford.

The book is the third such collaboration between Hockney and Gayford, and their regular emails and FaceTime calls, are as much a record of friendship conducted at distance, as a book about art.

Ranging across subjects, from colour and perspective, to sunsets, fame and the effects of aging, the book amounts in the end to something between a memoir and a collection of musings from a man who thinks deeply and widely, and communicates with ease. Whether he is talking about drawing, or Proust or Wagner, Gayford writes that it is “with such simplicity and ease that almost everything he says, journalistically speaking, is highly quotable”.

Hockney first began using an iPad in 2010, but a new app updated to his own specifications, helped to revive his interest in the medium at the beginning of 2020. Its great advantage is its immediacy – he doesn’t have to spend time preparing paints and brushes, he can just start work.

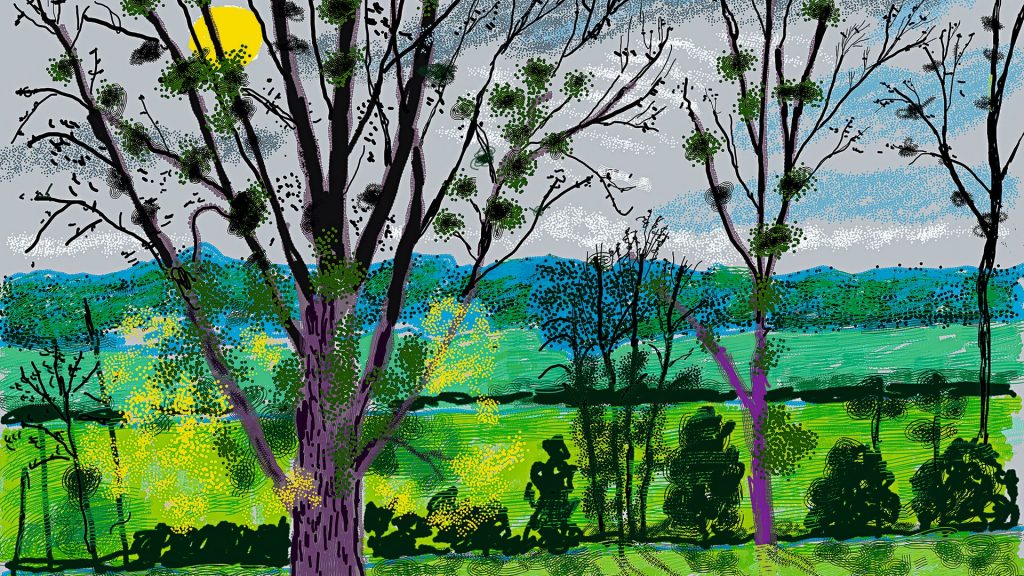

The vibrant colours so characteristic of Hockney’s recent years are applied with a huge vocabulary of marks and gestures – refined considerably since his early experiments with the iPad – that readily translate the unstoppable energy of the natural world into pictures.

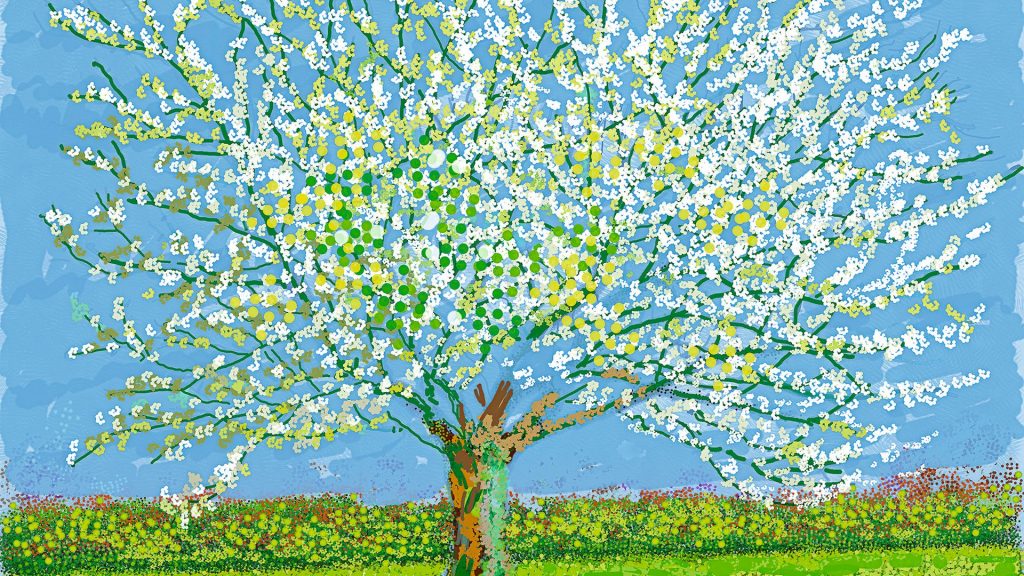

Their primal energy is unmistakably the very same life force that drives the new season: “The source of art is love. I love life,” said Hockney, a message that had special force at a time when life seemed to be simultaneously so precious and so devoid of interest.

The images strive for universality containing something of the mood and shared experience of lockdown. Hockney is well aware of the privileged circumstances of his own lockdown, and the new pictures, accordingly, capture the joy and energy of spring, but sound a cautionary note, too: “We have lost touch with nature, rather foolishly as we are part of it, not outside it”, said the artist. “This will in time be over and then what? What have we learned?”

Hockney has more popular appeal than most artists, but, as his most recent efforts in London show, he is also not afraid to cause offence, characteristics that may partly explain his enduring popularity; now 83, he has, commented his friend Melvyn Bragg, “been famous, more or less continuously, since he left art school”.

He is an inveterate observer of the seasons, and having painted several Yorkshire springs in the years leading up to 2013, he decided to paint spring 2019 in Normandy, where he had bought a house for that very purpose. In an email to Martin Gayford dated October 22, 2018, he described the attractions: “There are more blossoms there: you get apple, pear, and cherry blossom, plus the blackthorn and the hawthorn.”

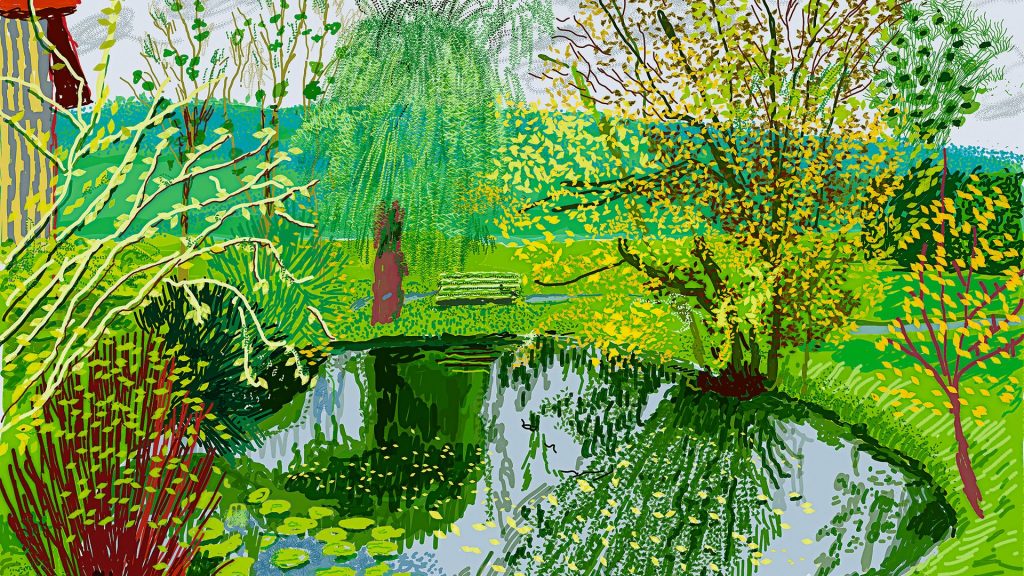

La Grande Cour was the first house that he and J-P saw, its half-timbered, “higgledepiggledy” structure the perfect vantage point from which to observe the transformation of the countryside. “It is a studio in a landscape,” writes Gayford, “Immersed in the natural world, in the midst of silence and living plants.”

Rural simplicity, structured around the natural rhythms of the working day and the turning seasons, seems to have increased their appeal for Hockney around the time of his 80th birthday in 2017, and he says that in the peaceful seclusion of La Grande Cour, he is more productive than ever.

He has always had a fearsome work ethic, and Gayford describes Hockney’s bedroom-cum-studio in Notting Hill in the 1960s, where a sign placed within sight of his bed read “GET UP AND WORK IMMEDIATELY”.

Aged 83, he is no less focused, and says “I’m less interested in what other people are doing. I’m just interested in my own work. I think I’m on the edge of something, a different way of drawing is coming through, and I can do it here. I couldn’t do it anywhere else: London, Paris, New York.”

Even so, life’s pleasures remain important to him, and as well as the “fabulous” food, France remains “a lot more smoker-friendly than mean-spirited England”.

Born in Bradford in 1937, Hockney moved to London in 1959 to study at the Royal College of Art. The limitations of his home country have repeatedly encouraged Hockney abroad: “Boring old England”, he wrote to Gayford. “You can’t do this, you can’t do that. That’s why I went to California all those years ago. I always thought there was so much self-hatred at home, and so many mean spirits. Well the mean spirits have really come out again now, it seems to me!”

Forever associated with his most famous painting, A Bigger Splash, 1967, California is Hockney’s best-known home from home. The clean, manmade lines of America could hardly contrast more with the “higgledepiggledyness” of Normandy, a favoured description that Hockney has borrowed from J-P, who Gayford describes as the artist’s “principal aide and, increasingly, the mainstay of his existence”.

The contrasting attractions of these various places are easily identified in Hockney’s paintings – the light and space of California, the green and rolling landscape of Yorkshire, the abundance, and particular quality of light in Normandy. Even so, they are connected by certain recurring themes which Gayford and Hockney tease out in conversation.

The swimming pool pictures for which Hockney is most famous, their pristine expanses of sun-baked blue water, shattered, ice-like, by a splash, or a ripple, offer an exotic setting for erotically charged depictions of the male nude. But they are also, fundamentally, paintings that grapple with the technical difficulties of painting water, as it changes constantly, reflecting and refracting light, sometimes offering an opaque surface, sometimes a window through to something else.

The same preoccupation can be seen in Hockney’s most recent iPad paintings: an April shower falling on the lily-pond at La Grande Cour is reduced to pattern and colour, but still it conveys exactly what is happening, as well as the strange and rather contradictory visual qualities of water. On a bright November day, the pond is perfectly still, its glassy surface offering reflections as vivid as the plants themselves. The busy movement of the river at the edge of the farm is captured in marks that seems as infinitely varied as the water they represent.

Hockney’s longstanding interest in water is inseparable from his interest in optics, a subject that he has pursued over decades with remarkable dedication and technical grasp. His controversial book, Secret Knowledge, 2001, proposed the theory that from the early 15th century, optical devices such as mirrors and lenses, were widely used by artists to aid their compositions.

Single-point perspective, the great discovery of the Renaissance, was a direct consequence of experimentation with optical devices and over the years, Hockney more than anyone else, has exposed the artifice of this system of constructing pictorial space.

In his explorations of the different ways in which pictorial space can be constructed and experienced, Hockney has experimented with multiple cameras, and different picture formats, including panoramas created from great concertinas of folded paper, inspired in part by the Bayeux Tapestry nearby.

Many of his insights come not just from the practical experience of making his own work, but from looking at the art of others, something that he has been doing in earnest for most of his life. In 1973, he moved to Paris where he lived near the Boulevard Saint-Germain, studying in detail the marks made by the great painters of the School of Paris – Picasso, Van Gogh, Matisse, Dufy.

Now, in his iPad paintings, the distinctive qualities of many of these artistic forbears are clear to see: the colour of Matisse, the masses of dots and dashes that in his work, just as in Van Gogh’s, create the impression of ceaseless movement.

For Hockney, this way of drawing is something of a metaphor for his life and work: he never stops, but is always looking to the next idea, or project. For an artist this prolific, errors of judgement and the occasional dud are an occupational hazard, evidence perhaps that his curiosity and frankly proclaimed love of life, continue undimmed by age.

Spring Cannot be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy, by Martin Gayford and David Hockney, is published by Thames & Hudson £25

David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020 is at Royal Academy from May 23 until August 1

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37