Before the professional ad industry took over and the watchdogs got involved, commercials had a more primitive and boisterous appeal.

In 1477 William Caxton, the man who introduced the printing press to England, fixed a slip of paper to a church porch to advertise the Sarum Pie, or the Ordinale ad usum Sarum, a handbook for priests.

The advertisement reassured clients that the text of the handbook was ‘truly correct’ and that the buyer ‘shal have them good chepe’ (cheaply) and he appealed: ‘Supplico stet cedula’ – please do not remove this notice.

In what would have been a delightful exhibition, The Art of Advertising at the Weston Library, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, scores of images dating from the dense print of Caxton’s notice to the flashy glamour of a 1930s jazz-age flapper in a shiny Morris car offer a glimpse into the spirit of the times – the inconsequential matters of passionate concern that have obsessed us over the centuries such as health and wealth, what to wear, how to look and how to behave.

Coronavirus has put an end to the show but a thoroughly entertaining and informative book by the show’s curator Julie Anne Lambert can be bought online and is ample compensation.

Most of the exhibits are from the John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera, accumulated by the late printer to the University of Oxford, who collected about 1.5 million items – mostly single-sheets, billboards, postcards, flyers and posters.

Johnson described his hoard as ‘everything which would ordinarily go into the wastepaper basket after use, everything printed which is not actually a book’.

What he rescued from the bin may seem trivial today, but as curator Lambert says: ‘Their messages are now redundant, their immediacy, sometimes even their meaning, lost. And yet, although they were not conceived for that purpose, advertisements bear witness to their age, often encapsulating its zeitgeist.’

The result is quaint, curious, and with the perspective of 21st century sensibilities, absurd and often, downright dishonest: shaving razors for use while hunting? Cadbury’s cocoa more nutritious than meat, eggs and bread combined? And what about the prospect of immortality offered by Blackham’s Vegetable Tonic which promised to ‘utterly destroy’ the ‘Death Microbe’? Take your pick.

The exhibition follows the development of printing from the simple letter press of Caxton’s day, to the wood cuts from the 15th and 16th centuries and on to the 19th century with the invention of chromolithography, a method for making colour prints using chemicals instead of the raised image of a relief.

In a kind of symbiosis, as the technologies improved they reflected a society which, for some, became increasingly sophisticated and wealthy and to whom the advertisers targeted their wares accordingly.

Like Caxton’s little poster the earliest adverts were densely displayed and came straight to the point. The Elixir Stomachicum; or, the Great Cordial Elixir published in 1698, claimed to be ‘of a Delicate Flavour, and pleasant (though bitter) Taste to be drank at any time , but especially in a Morning in any Liquor, as Ale, Tea, Canary (a sweet fortified wine) etc’. It promised to ‘ease scurvey, purifie the Blood, Expell Wind, for all indispositions of the Stomach’ and boasted that it ‘excells any One medicine ever made public’.

By the early 19th century thanks to wood engraving, a refinement of the wood cut, these wordy ads were increasingly replaced by dramatic posters such as Lotteries End for Ever in which the message from a strident bell ringer is picked out in bold red and black lettering which could easily be read by passers by in the street.

Simple, direct, but with the introduction of chromolithography, the range and versatility of the displays moved up several notches – and none more than with the promotion of Pears soap in 1887. Thomas Barratt, managing director of the soap company bought the copyright to A Child’s World by the Royal Academician John Everett Millais which depicted a boy gazing at bubbles as they floated off into the unknown. Barratt cheekily added a bar of Pears soap, the brand name and a new title, Bubbles.

Millais was horrified but without a copyright had no choice but to accept the inevitable as his re-worked image became one of the most enduring adverts until the 1920s, appearing on billboards and in books more than three million times.

A soap rival, Sunlight, played a similar game with Charles Burton Barber, a regular exhibitor at the RA transforming A Girl with Dogs into The Family Wash and a painting by Academician William Powell Frith, A New Frock, was transformed by Sunlight into a child holding up her clothing with the slogan ‘So Clean’.

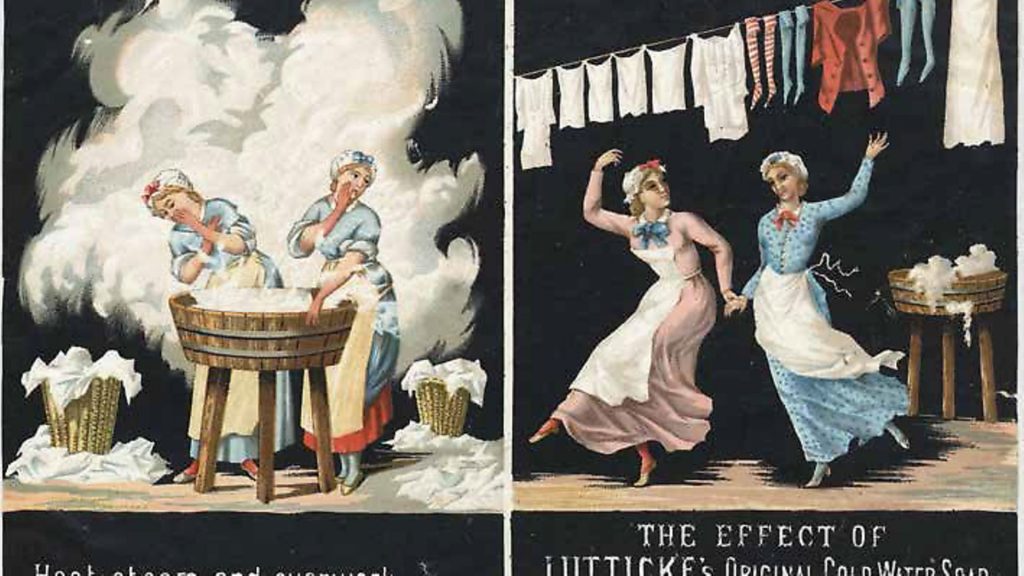

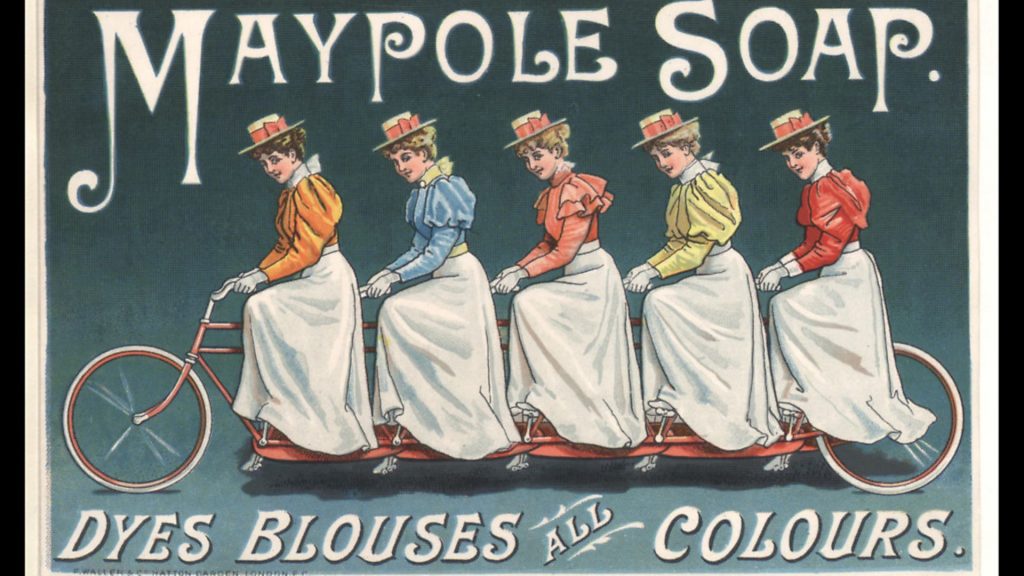

Being clean and busying oneself with the housework was a constant theme and the adverts of the 19th century are reminders that this was a world where the affluent had servants who, of course, were happy with their lot and eager to use new products such as Lutticke’s original cold water soap.

The ad shows contrasting images, one with two servants coughing in the steam and weighed down by the misery of washing day, and in the other, dancing for joy once they used the soap which promised ‘no heat, no steam, no chapped hands’.

In another, ad ‘For spring cleaning use Calverts’, the lady of the house simpers admiringly as her servant cheerily washes down the floor with a damp rag, a bucket and the all-new No.5 carbolic soap.

By the end of the century the world of women is changing. Not only do the advertisers target them as the person in charge of the household budget but also, then as now, a pretty female face makes a more appealing pitch to the household member, who tended to provide the money. The husband.

Some themes remain familiar to readers of today’s women’s magazines; the Royal Worcester Adjusto corsets for the ‘generous or fuller figure’ promises ‘luxurious freedom and comfort’ and Figuroids tablets are marketed as ‘the only method by which it is possible to remove fat from the body’.

But the ads also recognise that women were also gaining some independence.

‘Vote for Nixey’s Boot Polish’ combines a reference to the suffragette movement with a, frankly, deranged-looking woman stepping out confidently in her shiny boots clutching a poster while the right of women to smoke is encouraged by a tobacco maker with the words; ‘It is now fashionable for ladies to smoke dainty little cigarettes and why not?’

In 1908 a confident young woman, independent and free spirited, strides out as Miss Remington who enthuses over the portable typewriter she is carrying – ‘delightful to operate and so compact’. Though it does rather confirm her role as secretary – the boardroom is some way off for the Miss Remingtons of this world.

By now – the end of the Victorian era and the start of the 20th – the advertisers tug at the purse strings by using glamour and celebrity. Mennen’s borated talcum powder claims the endorsement of such stellar names as actresses Mrs Patrick Campbell and Ellen Terry as well as opera singers Adelina Patti and Dame Nellie Melba with the claim, ‘The above celebrities all recommend ‘Mennen”.

Ellen Terry was happy to pose for ‘Koko for the Hair’, vouchsafing she had used the product for many years and ‘can assure my friends that it stops my hair from falling out… and is the most pleasant dressing imaginable’.

With no control over content – the Advertising Authority launched only in 1962 – the royal family, the ultimate in celebrity, was exploited with scant regard to propriety.

Matchless metal polish managed to combine the death of the Queen while celebrating her successor, the newly-crowned Edward VII. ‘A ‘Matchless’ Reign’ and a ”Matchless’ Metal Polish’ it declared and exhorted consumers to ‘BE LOYAL! DON’T PURCHASE FOREIGN POLISHES’.

Victoria looks on severely as the public is being encouraged to ‘Ask for Golfer Oats’. The makers capitalised on her diamond jubilee year (1897) by proclaiming that their porridge was ‘the latest development of jubilee year … unequalled for Infants and Invalids’ and claiming that their porridge and the Queen together were ‘the two safeguards of the constitution’.

By the 1920s the advertisements had long substituted laborious accounts of a product’s virtues by concentrating on the brand’s image – often with examples of stylish commercial art.

Aubrey Beardsley drew posters for the literary periodical, The Yellow Book, and Dudley Hardy did as much as anyone to influence the new style with his poster of an effervescent girl dressed in yellow advertising a weekly magazine, To-day.

The Beggarstaffs – a pseudonym for designers William Nicholson and James Pryde – brought strong outlines to Rowntree’s Elect Coffee, and Maurice Greiffenhagen used only three blocks of colour – red, black and off-white – to make an impact with an elegant lady reading the Illustrated Pall Mall Budget.

Perhaps the most distinctive of the commercial artists was John Hassall who added humour to simple depictions of everyday life. A bald man scratching his head, searching for his Andrews Liver Salt which remains unseen in his back pocket, is a classic. ‘I Must have left it behind’ reads the slogan.

For most of the years covered by the exhibition the impetus for the advertisement came from the printer or the owner of the product or store but by the 1930s, the advertising agency was taking over, offering a complete professional service.

One company boasted that it required only ‘details of the story you wish to tell, the client you wish to reach, and the openings you wish to develop’ for it to launch a campaign.

In consequence the hidden persuaders of the ad world became a multi-million pound industry. Today the United Kingdom ranks fourth among the world’s advertising markets with expenditure estimated at more than £20 billion and, as one might expect, earnings in the industry are also high with ad giants Saatchi and Saatchi, for example, topping the pay league with income per head at £172,487, according to trade magazine Campaign in November 2018.

In fact, vast amounts of money have washed around the industry for years. In 1863 one Thomas Holloway, seller of pills and ointment, was at pains to explain the value of advertising because he was not prepared to settle for a ‘limited reputation’ but instead ‘to be content with nothing less than girdling the globe with Depôts of my remedies’.

To achieve that in that one year alone, he invested £40,000 – about £5 million in today’s figures. Even Saatchi and Saatchi would be impressed by that.

• The Art of Advertising, by Julie Anne Lambert, £21.70, available online

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37