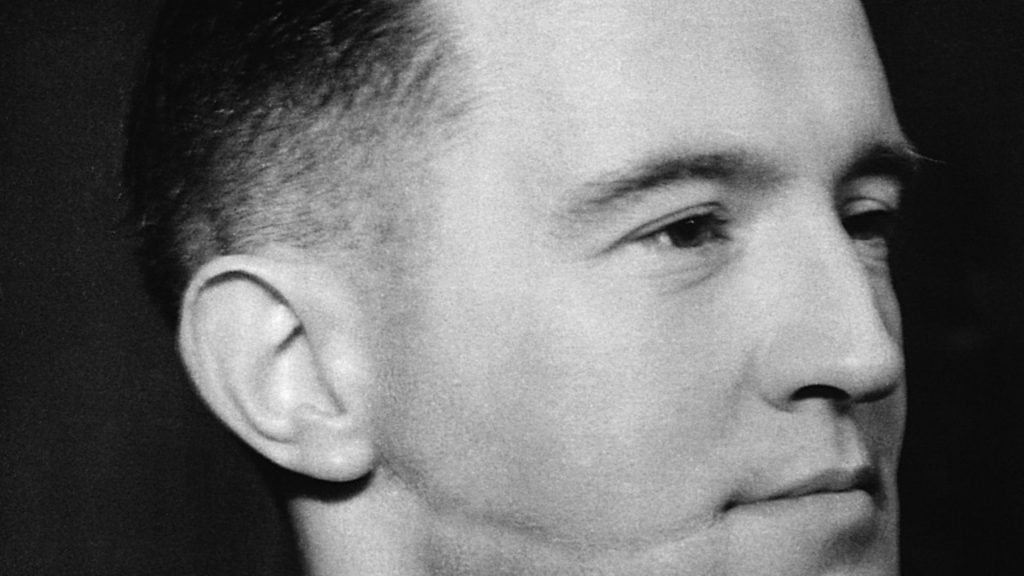

The broadcaster and traitor – captured 75 years ago – exerted a mesmerising influence over his willing audience, says RICHARD LUCK.

‘Germany calling, Germany calling’ – even today, those words can send a shiver down one’s spine. Heaven knows how chilling they must have sounded when broadcast out of British radio sets at the height of the Second World War.

As the bombs rained down on every major manufacturing site in the UK, the man with the highly-affected aristocratic accent poured scorn on the Allies’ chances of surviving the Nazi military onslaught.

Defeat was inevitable, his listeners were assured; simply surrender to the Fuhrer and the warm embrace of national socialism and your normal programming would resume forthwith.

Though designed to break the resolve of the British, the Lord Haw-Haw broadcasts, as they became known, had quite the opposite effect; strengthening the resolve of his listeners to do whatever they could to bring about Hitler’s defeat. But who was the man with the public school vowels and the abrasive tone? And how did he come to be known as Lord Haw-Haw?

We have Daily Express radio critic Jonah Barrington to thank for the nickname, his pieces on the Nazi broadcasts never failing to point out the speaker’s ‘haw-hawing, dammit-get-out-of-my-way tone’.

The broadcaster’s identity, however, is more elusive than you might have been led to believe. For there were in fact several Lord Haw-Haws – or, at least, there were a number of Nazi-backed radio broadcasters who used the British voice of wisdom and experience over the airwaves to convince the Allies that the gig was up.

Indeed, before William Joyce entered the picture, German radio host and PG Wodehouse fan Wolf Mittler ‘graced’ the airwaves with his best – actually rather ordinary – Bertie Wooster impression. Then, after Mittler voiced his dislike for both the material and the cause, he was replaced by Norman Baillie-Stewart, a former British army officer who had been kicked out of the forces in the 1930s for selling military secrets to the Germans.

It wasn’t until September 14, 1939, less than an week after Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany, that William Brooke Joyce first got behind the microphone.

His journey to Berlin had begun half a world away in Brooklyn, New York, in 1906 where he was born in to an Irish father and English mother.

Three years later, the Joyce family returned to the old country, settling in County Galway. With Ireland still part of the United Kingdom at the time, the Joyces were British, a fact that would prove of some import later in William’s life.

Lovers of Britain and its monarchy at a time and in a country where antipathy towards both was in the ascendant, the proudly Protestant Joyces were spurned by their Catholic neighbours.

Come the war for independence, the teenage William wrapped himself in the union flag, informing on the IRA for the king’s army. When the republicans got word of this perceived treachery, they sought to snuff out Joyce; this at a time when the IRA tended not to execute juvenile informers.

A fortuitous change of address spared William’s life in the short-term, while relocation to Worcestershire marked the beginning of the next chapter in his life.

Although he flirted with a military career, Joyce ended up studying English at Birkbeck College, graduating with a first. It was then, after unsuccessfully applying for a Foreign Office position, that fascism first entered his life.

The movement made quite an impression on Joyce. Indeed, he would take great pride in claiming that his pronounced ‘Chelsea smile’ – a scar running from his ear to his mouth – had been a gift to him from Jewish communists at a political meeting in Lambeth in 1924. Though the meeting and the communists had both been real enough, Joyce biographer Colin Holmes is convinced that the razor-wielding assailant was in fact both Irish and female.

Joyce officially joined the British Union of Fascists in 1932. Impressed by his way with words, Oswald Mosley charged him with writing and delivering speeches. Joyce was also held in high regard as a rabble-rouser, willing and able to back up his invective with a well-aimed fist or boot.

At one point recognised as the BUF’s deputy leader, Joyce’s time with the group was cut short by infighting and budgetary issues. According to Mosley, Joyce was a traitor to the movement, obsessed with anti-Semitism at the expense of all other issues.

If he was no longer in league with the Black Shirts, Joyce’s time with the group meant that, with war looming, he was among the various ne’er-do-wells the government was interested in interring.

So it was that, towards the end of August 1939, William and his wife Margaret travelled to Berlin. According to some intriguing accounts, he was tipped off about his impending arrest by handlers in MI5 who had previously recruited him to report on the fractious Black Shirts.

Once in Germany, Dorothy Eckersley – another displaced BUF sympathiser – suggested that, with his writing and speaking skills, he’d be a good fit for radio work. One audition later and Joyce was unveiled as the new and improved Lord Haw-Haw. It was a position he would hold until the spring of 1945.

Initially based in Berlin, Joyce would see an awful lot of Germany and its newly-occupied territories as the Nazis sought to keep him from Bomber Command’s clutches.

Employed by the national radio corporation Reichsrundfunk, Joyce’s flagship show, Germany Calling aired on medium wave.

A network of Nazi-controlled stations stretching across Germany and later France and the Low Countries ensured that a strong signal could be picked up on the other side of the Channel.

Rather than bleeding into regular programming as has often been depicted, Germany Calling was available to British listeners in much the same way as the pirate radio stations were in the 1960s.

Listening to Joyce wasn’t actually against the law but the government openly discouraged the general public from lending their ears to Lord Haw-Haw.

However, many seemed keener to listen to him than to the official guidance. At some points in the war, around half of the British listening public seemed to be tuning in to Haw-Haw.

Historian Terry Chapman, in a piece for the Imperial War Museum, explained: ‘The BBC… undertook in early 1940 a special study of the effects of the German broadcasts. At the end of January 1940, one out of every six adults was a regular listener [to Germany Calling], three were occasional listeners… At the same time, four out of every six people were listening regularly to the BBC News.

‘A number of reasons were put forward for this large audience,’ Chapman continues. ‘[Over half] of those questioned listened ‘because his version of the news is so fantastic that it is funny’… A large percentage tuned in ‘because so many other people listen to him and talk about it’. A bricklayer’s labourer told one reporter: ‘There’s a feeling you can’t turn off. You’ve got to listen to him.”

These accounts get to the heart of the Haw-Haw appeal, and therefore the power he wielded over his listeners. Many people have described finding him ‘amusing’. For a start, there was the accent – cartoonish, even at the time. But it was just part of a radio persona that was able to pass into myth, a phenomenon that existed far beyond banal realities of a bitter man sitting behind a microphone in a studio in the Third Reich.

For instance, stories spread in Wolverhampton that when the town clock stopped one night, Joyce had reported the fact 20 minutes later. Elsewhere in the Midlands, an ammunition factory suffered a drop in production when it was believed that Joyce – who, of course, had no military role – had threatened to bomb their new paint shed.

In Shoreditch, locals believed that he had had one street bombed because he had been beaten up there.

His listeners may not have nodded along to what Joyce was saying – there is no evidence that his audience were attracted to his broadcasts because they agreed with them – and yet, at a time of great uncertainty, with the prospect of violent death literally hanging over their heads, they tuned in night after night.

His propaganda did not ‘work’ in the straightforward sense of the word. His listeners were perfectly capable of recognising his lies and nonsense. Indeed, that was part of the amusement. Yet that did not diminish his power. His broadcasts were able to unsettle his audience. They provided the besieged British with an unnerving glimpse of the enemy, and he was close-up, speaking their own language and dripping his poison as they sat in their own living rooms. Rather than just switch their sets off, many must have found this a grimly-fascinating experience.

And what did this addictive shock jock have to say to his audience? Everything from out-and-out fabrications – Joyce insisted that the Nazis had no interest in occupying the Balkans – to the celebration of German military triumphs such as the Nazis’ conquest of Denmark and Norway.

Lord Haw-Haw also took great pleasure in insisting that the British were a petty, trivial people who had neither the stomach for war nor sufficient honour to conduct conflict in a civilised manner.

And Winston Churchill? In Joyce’s opinion, the prime minister was ‘[not] the servant not of the British public, nor of the British empire, but of international Jewish finance.’

Anti-Semitism was never far from Lord Haw-Haw’s lips, either. ‘I don’t regard the Jews as a class,’ he’d claim in one broadcast, ‘I regard them as a privileged misfortune.’

Such was his noxious fame – fuelled by its curious mix of ridicule as much as fear – spread as far as Hollywood, where it helped inspire the 1942 film Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, which pitted the detective against a Nazi propagandist – complete with a distinguishing scar – who uses the anonymity afforded by the airwaves to spread fear the width and breadth of Britain.

Just as fate finally overtakes the fictional villain, so it was catching up with Joyce. As the war progressed, and Nazi fortunes declined, he became a parody of his former self. With his drinking increasing as quickly as the Allies were advancing, Lord Haw-Haw’s final broadcasts were all but unintelligible.

The last time he slurred ‘Germany calling’ was April 30, 1945, the same day Hitler committed suicide. In happier times, Joyce had been awarded the War Merit Cross by the Fuhrer. Now, with his beloved leader dead, there was nothing left for Lord Haw-Haw but to go into hiding.

Since the Allies were familiar with his voice and Joyce himself had regularly mentioned his real name during broadcasts, his hopes of alluding capture were slim. When the moment of truth came, it was on May 28 in Flensburg, the town near Germany’s Danish border that served as the last capital of the Third Reich. While walking through the local forest, Joyce encountered two British officers collecting firewood.

‘When he saw what we were doing, he pointed to a pile of logs with his walking stick and spoke first in French,’ Lieutenant Geoffrey Perry recalled in an interview with the BBC. ‘Then, in English, he said, ‘There are three or more [logs], here.’ When I turned to [Captain Bertie Lickorish], he said, ‘That sounded terribly like William Joyce’ … I challenged him and said, ‘You wouldn’t be William Joyce by any chance, would you?’ His hand reached for his pocket – I thought he was going for his gun – I drew my own pistol, aimed low and fired.’ Injured and identified, for William Joyce, the war was over.

As he recovered from his wounds, his prosecution for treason was prepared by the British. But could such a charge be levelled against the American-born Irishman? Geoffrey Robertson, the human rights barrister, has talked at length about the Joyce conviction and is convinced that it was motivated by revenge rather than adherence to the law.

The counter argument concerns the fact that when Joyce was resident in Ireland it was still part of the United Kingdom and, as such, Joyce was a servant of the crown. Those in support of the conviction also point to Joyce having obtained a British passport – albeit by nefarious means – and participated in UK elections.

It was enough to secure his conviction and he was executed at Wandsworth Prison on January 3, 1946, under the watchful eye of Albert Pierrepoint, another 20th century character of sinister fascination.

Joyce’s execution helped secure his notoriety. He was the only one of 40 British subjects – and there were no legal question marks over their status – who had broadcast from Germany during the war to suffer this fate. The reason for his special treatment appears to have been a recognition of his talent. None of his fellow pro-Nazi broadcasters – which included his own wife, known as Lady Haw-Haw – had achieved anything like the same dubious fame. The precise alchemy that had created this ‘success’ must have been a combination of both his persuasive radio persona and the heightened sensitivities of his audience.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37