He seems the quintessential American writer, but Truman Capote’s career hinged on spells he spent in Europe. RICHARD LUCK explains how the continent played a key role in shaping Capote’s life, his writing and his masterwork, In Cold Blood.

Yes, Truman Garcia Capote first came to Europe in the hope of winning the affections of fellow writer Jack Dunphy. In 1949, the two men – Dunphy the elder by a decade – embarked on a tour of Italy, visiting Venice, Florence and Naples before settling in Rome. With Dunphy positively responding to Capote’s advances, the younger man discovered a happiness that, among other things, inspired him to begin writing what became The Glass Harp, his second novel.

In Capote: A Biography, Gerald Clarke remarks that, while the initial desire to explore Europe might have been Dunphy’s (“Jack wanted to travel and Truman wanted to please him”), it was Capote – or more specifically, his writing – that benefited most from the change of scene.

“Truman loved New York,” writes Clarke. “[He] loved it so much that he found it hard to write when it was so tempting to go out on the town. New York was a kind of addiction. He realised that if he wanted to write – and that’s all he wanted to do – he would have to do it elsewhere.”

The continent also laid on some exciting opportunities, such as the time Capote was summoned to the Amalfi Coast to rewrite the John Huston movie Beat The Devil (1953), which was being shot in the area. Writer-director Huston and leading man Humphrey Bogart were unhappy with the film they were shooting and so put Capote to work – he’d often write a scene in the morning in time for it to be filmed in the afternoon.

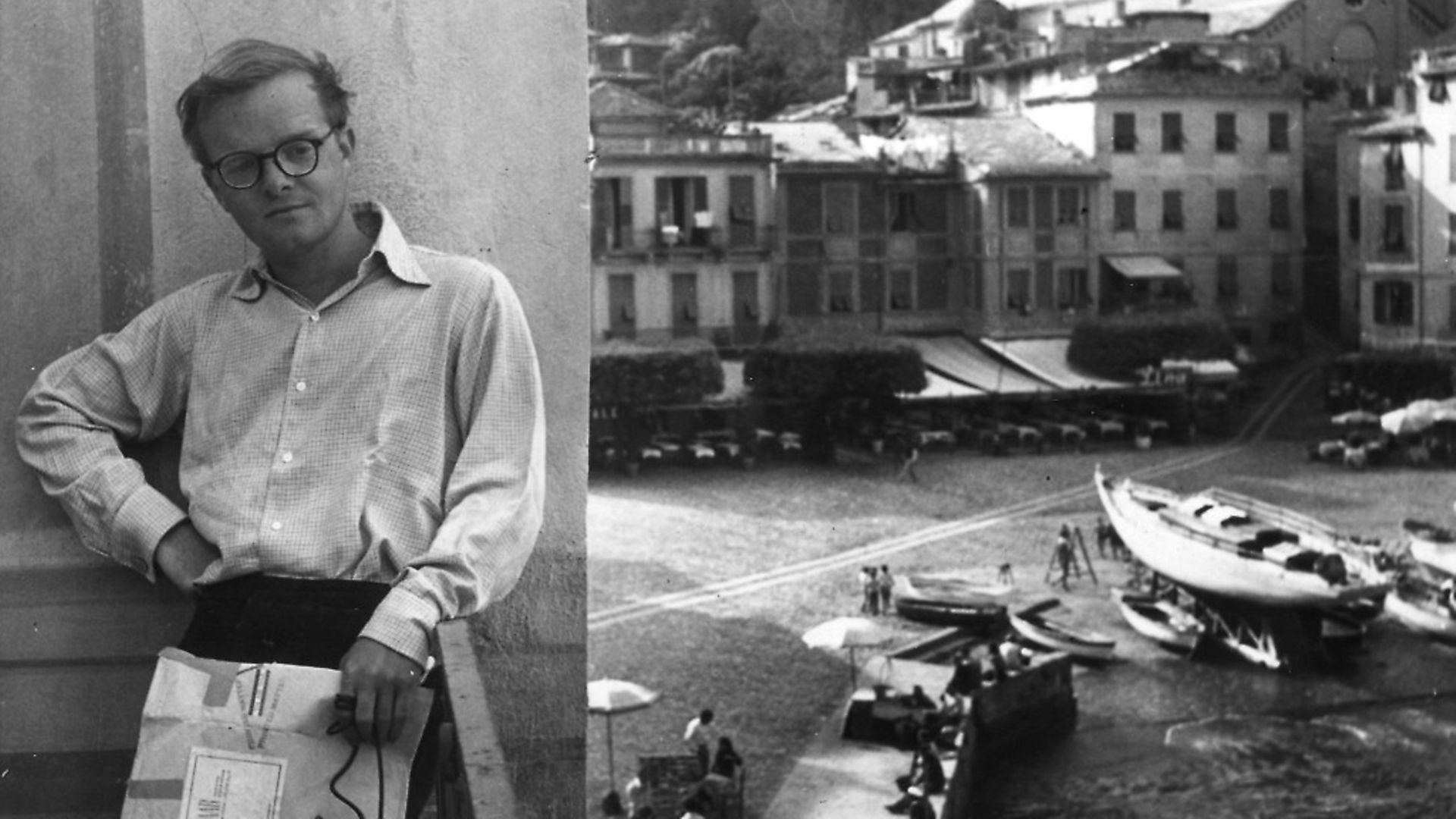

The Beat The Devil gig gifted Capote enough money and sufficient anecdotes to live on for some time to come. So it was that Capote and Dunphy hit the Italian Riviera in the spring of 1953. They stayed in Portofino until October, by which time Dunphy’s boyfriend would be a bona fide literary star.

On the back of his debut Answered Prayers and the aforementioned The Glass Harp, Capote was a man everybody wanted to meet. Rex Harrison, Noel Coward, Tennessee Williams, John Gielgud – each and all saluted the enfant terrible of the English language. Of those who came to Portofino specifically to spend time with him, Capote drew particularly close to the photographer Cecil Beaton, and the unlikely pair – Capote looking almost childlike with his shorts and unkempt hair, Beaton the epitome of English refinement – were often to be seen deep in conversation.

The summer soon devoured by endless cocktail hours and the odd spot of writing – Capote’s working holiday yielded the libretto for musical House Of Flowers – Capote and Dunphy left the riviera forever changed. Yes, other seasons had posed him greater challenges, but the quasi-spiritual experience Capote underwent in Portofino altered his estimation of both himself and his work. Whether it made him a better person is debatable. That his confidence as a writer increased is undeniable.

From the Mediterranean coast to the heart of a Russian winter, Capote’s next major European adventure saw him head to the Soviet Union to cover a tour by New York’s Everyman Opera Company. An olive branch exercise at a time when the Cold War was really biting, an African-American cast performing Porgy And Bess before the politburo was the sort of highly unusual event that merited Capote’s attention.

With Ira Gershwin’s wife on hand to ensure her husband’s work went unmolested, Capote made copious notes as the Everyman’s every man and woman performed before bemused audiences in Leningrad and Moscow during the festive season of 1955.

In years to come, the Everyman exercise would be acknowledged for playing a role in black America’s quest for equal rights. For Capote, however, the tour was but an excuse to experiment with new journalism, the form with which he would become synonymous.

The Muses Are Heard (1956) found the author complaining about the quality of Soviet hotels and remarking upon Russia’s sexual prudishness, Porgy And Bess proving far too raunchy for the good folk of the USSR. That Capote thought the Everyman “a second-rate company” also comes across in his mischievous account of the ultimate culture clash.

With Capote being upfront about parts of The Muses Are Heard being embellished if not quite fictionalised, one can’t take the story’s revelations too seriously. Still, as he flirted with new journalism, Capote found a way of tackling the gravest of subjects in a fresh, dynamic fashion. It’s no understatement then to say that The Muses Are Heard, and the author’s mission to Moscow were crucial to his developing the technique that produced In Cold Blood, the non-fiction novel that ensured Capote’s place in America’s literary pantheon.

Before then, though, Europe was to play a role in the story behind his other great classic, Breakfast At Tiffany’s, after it encountered problems before publication. Burnt out upon the novella’s completion in 1958, Capote headed for the Greek islands, convinced that the book’s language and subject matter would scupper any chance it had of going into print.

Sure enough, his editor had plenty of problems with the tale and peppered Capote with telegrams and calls throughout his stay on Paros. Rather than getting caught up in a crippling dispute, Capote set about enjoying his holiday.

Good food, great reading (Proust, Raymond Chandler), endless sunshine – what could have been a fraught period in the writer’s life began to resemble Capote’s idyllic stay in Portofino. The resemblance between the two eras was re-enforced by the presence of Dunphy and Beaton, the photographer having promptly responded to an invitation to join the pair on Paros.

The weeks of swimming and walking and talking that followed left Capote ready to return to New York and fight the last few rounds needed to bring in Breakfast At Tiffany’s.

When the novella was eventually published in November 1958, Norman Mailer – a man about as far removed from Capote as its possible to be without belonging to a different species – described the author as “the most perfect writer of my generation – I would not have changed two words of Breakfast At Tiffany’s.”

Mailer had fewer good things to say about 1965’s In Cold Blood (he described it as “A failure of the imagination”), but no matter. A forensic account of a mass murder in rural Kansas, In Cold Blood is an extraordinary accomplishment, widely and rightly regarded as Capote’s masterpiece. And as the book was in part inspired by his excursion to Moscow, so it was Europe that enabled Capote to fully bring In Cold Blood into being.

In the course of researching his tome, Capote had both befriended the friends and neighbours of the slain Clutter family and drawn close to the men found guilty of their slaughter, Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. According to some accounts – including the 2006 film Infamous, starring Toby Jones as Capote – the writer was actually physically involved with Smith.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the Clutter tragedy took a great emotional toll on Capote. To make matters even worse, the writer didn’t have an ending for his novel, at least not until the death sentence on Hickock and Smith had been served. That something as ultimately trivial as a book’s resolution rested on the killing of two people he’d come to consider friends so upset the author that he turned to drink and drugs in hope of finding respite.

Then, just when the bottle ceased to provide succour, Capote received a phone call from Dunphy. Currently writing on the Costa Brava, Dunphy insisted that his frazzled boyfriend join him in the village of Palamos. And so it was that Capote’s compelling story of murder, small-town American style, wound up being written beneath the Spanish sun.

Between the publication of In Cold Blood in 1965 and his death in 1984, Capote globe-trotted less and less. As a resident of New York City, he acquired notoriety courtesy of his regular visits to Studio 54, the famed Manhattan nightclub that seemingly ran on a blend of celebrity, sweat and cocaine.

A keen drinker and recreational drug user since his youth, Capote’s new-found appetite for coke so inflated his ego, it all but burst. The drug and its effects certainly contributed to the author falling out with pretty much everyone he’d met on the way up. Even one of his very oldest friends, Harper Lee, stopped returning his calls, perhaps because Capote did little to quell rumours that his involvement with To Kill A Mockingbird extended beyond his having inspired the character of Dill Harris.

Sadly, this aimless period of debauchery is what springs to many people’s minds upon mention of Capote. Whether it’s going to Studio 54 in his pyjamas or mislaying thousands of dollars worth of coke on the short journey from a cab to his apartment, it’s easy to understand why these anecdotes have endured. Contrast such stories of excess with Capote’s sedate but nourishing European excursions and you see that, while the former ultimately destroyed his gifts, without the latter, there would have been no high point from which to decline.

Ernest Hemingway, Arthur Miller, Gore Vidal – what the continent did for them it also did for Truman Capote. “Writing has laws of perspective,” the author observed in a 1957 interview. To write so well about America, he had to cross the Atlantic, for it was from Europe that could he see his homeland in its entirety. Its flaws, its follies, its promise – who’d have imagined that, to so perfectly capture Manhattan and small-town America, what you first needed to do was set up shop in the Mediterranean.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37