When Do The Right Thing was released it was considered an incendiary polemic for racially-charged times. Thirty years on, JAMES OLIVER finds it has lost none of its power.

It gets hot in New York city and as temperatures rise, tempers fray. That’s one of the reasons why Do The Right Thing got the reception it did on first release: several critics took against the film not just artistically but morally.

It was a ‘dangerous’ film, they wailed; one that might lead to civil disobedience and worse.

It didn’t, of course (how could it?) and those dire predictions of unrest have been filed away and forgotten. Instead, as it turns 30 this year, Spike Lee’s third film is being treated to the sort of celebrations that show it is now considered a classic, with the customary anniversary re-release and deluxe blu-ray edition.

But it’s worth remembering those wrong-headed early takes: Do The Right Thing trades in issues that frightened a lot of people and frighten them still – it might be a ‘classic’ but it’s still horribly relevant.

It’s set on the hottest day of the year, on a block in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a historically African-American neighbourhood in Brooklyn. One of the local hang-outs is Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, a fast-food joint run by one of the few white guys in the neighbourhood (played by Danny Aiello); he’s a decent guy, who likes and is liked by his customers, and he’s proud of his own heritage, so much so that he has a wall of fame, photos of other Italian-Americans, like Frank Sinatra.

The trouble starts when someone asks why he hasn’t got any black faces on the wall – after all, most of Sal’s customers are black.

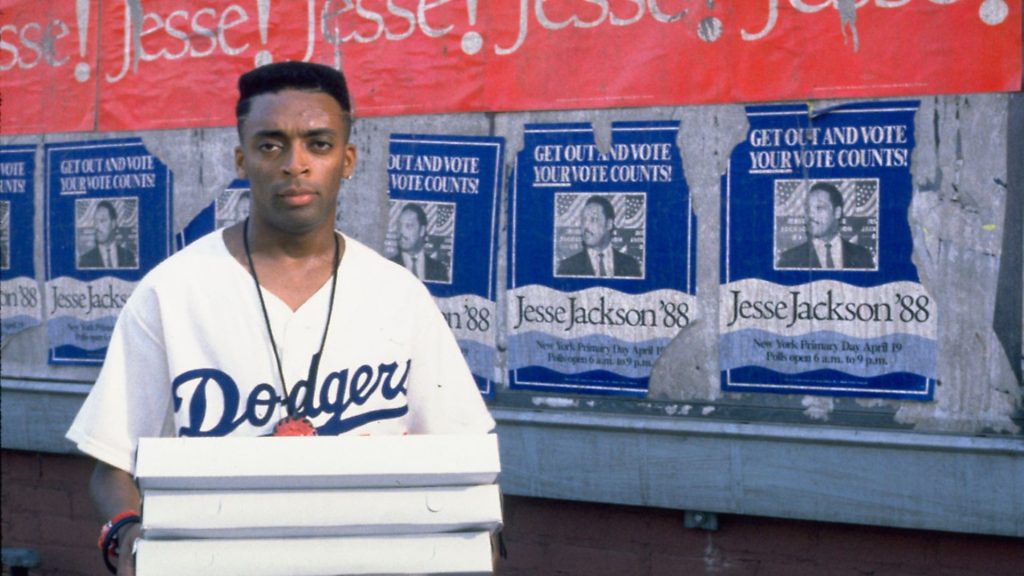

That disagreement will escalate, but before it does, it needs to be noted that this isn’t (just) a film about rage; Lee could have set it on another, cooler, day and still produced a masterpiece just by focusing on the locals. This is a vividly drawn community, and we get to hang out with them at length; Mookie (Spike Lee himself), Sal’s feckless delivery guy; philosophical drunk Da Mayor (Ossie Davis); Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), his boombox pumping out Public Enemy all the while; the guys on the corner, the kids on the street…

But the thermometer is pushing 100°F and the police are cruising around. Lee was inspired to make the film after a couple of infamous incidents involving the cops. There was the one concerning Eleanor Bumpurs in 1984; 76 years old, with mental health issues, she was holding a knife when she opened the door to the police who had come to evict her; they shot her twice, fatally. She was black. So was Michael Stewart, a graffiti artist who died in a chokehold administered by New York’s finest.

This is what made the film so controversial; Lee was picking at America’s most painful scab. If conversations about race are fraught today, they were even more so in 1989 when there was a comfortable white majority with even more conservative attitudes than now. This was 25 years before #blacklivesmatter, and there were a lot of people who didn’t want to hear about institutional racism or police brutality.

Those who accused Do The Right Thing of being ‘agit-prop’, however, missed the point. This isn’t a sermon, nor are the characters mouthpieces for what their creator believes; as everyone who has ever read an interview with Lee will know, he’s never needed anyone or anything to speak on his behalf, thank you very much. Racism feature here because it features in these people’s lives. But ultimately, this is about a bunch of guys who are spoiling for a fight.

(And it is guys; the women here – from Mookie’s sister Jade (played by Lee’S own sister Joie) or neighbourhood matriarch Mother Sister (Rubie Dee) – are a moderating influence, or at least try to be.)

Beyond the true stories of police brutality, Lee was inspired by other sources: “I remember seeing an old Twilight Zone,” he told his biographer Kaleem Aftab, “where a scientist had conducted a study that the murder rate goes up after the temperature hits 95 degrees.” Animosity below the surface is drawn upwards; the heat dries everything out and fires are started by a single spark.

Bad things are said here, but it’s not just from white to black. Lee is allergic to cliché, and is determined to mix things up; a Korean family have opened up a grocery store and are subject to derision and outright abuse from the locals.

What’s more, the director shows tremendous empathy – in the truest sense of that much-misused word – by seeking to understand his most racist character, Sal’s son Pino (John Turturro); you won’t agree with him (or at least it’s very much to be hoped you won’t) but he’s not the cartoon bogeyman he might so easily have been.

Lee doesn’t always get his dues as a filmmaker; he’s such a brilliant polemicist that other aspects of his films tend to get overlooked. But they’re on full display in Do The Right Thing, starting with one off cinema’s greatest credits scenes, with Rosie Perez dancing, grinding and punching her way through Fight the Power by Public Enemy (written for this film, fact fans), perfectly setting you up for the next 120 minutes.

Do The Right Thing premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and there were high hopes that it might take the top prize. Instead, the Palme d’Or went to sex, lies and videotape (itself a seminal film). It was a defeat that Lee took with good grace: “I have a Louisville Slugger baseball bat with [Cannes Jury president] Wim Wenders’ name on,” he said at the time, responding to reports – strenuously denied – that Wenders denied the film the title because he found Lee’s character ‘unheroic’.

Soon enough, Lee would have bigger issues than sour grapes, with the anguished suggestions that the film promoted violence. It had the misfortune to drop at a time when racial tensions were higher than normal; earlier that year, a young white woman had been attacked, beaten and raped in Central Park. The attack was so vicious that she couldn’t identify her assailant but the NYPD arrested five black youth, even though many believed they had the wrong people.

As it happened, they had; DNA would later incriminate the real culprit, but a lot of New Yorkers were furious at the Central Park Five (as they came to be known), displaying a scarcely-disguised racism. One local businessman took out a full-page advert in the New York Times demanding the restoration of the death penalty for them.

Plunged into this febrile atmosphere, Do The Right Thing earned an unfair reputation for being incendiary, something that dogs it to this day. Happily, we can see it more clearly now. It’s a film about racism, about hate and a film that knows we need to chill the f**k out.

Nor has it dated; if anything, it may be more on-point than ever. After all, the local businessman who demanded the Central Park Five be executed is now president of the United States of America.

A restored version of Do The Right Thing is released in cinemas on August 2 and the Criterion Collection blu-ray is available from August 26

BEHIND THE SCENES

The film had the working title, Heatwave, and several techniques were used to create a sense of sweltering temperatures on screen.

Cinematographer Ernest Dickerson ensured plenty of ‘warm’ colours appeared – yellows, reds, earth tones, amber – and avoided blues and greens, which can have a cooling effect. That rule extended to costuming, set design, and props, which is why almost every scene has at least one red element in it.

Cans of Sterno – a jellied fuel – were also placed near the camera, so the vapour created a hazy, wavy effect.

The film was shot entirely on Stuyvesant Avenue, in Brooklyn. One reason it was chosen was because it runs north-south, meaning – since the sun travels east to west – one side would always be in the shade. This meant that filming could take place even on cloudy days, as it could be made to appear that the action was simply taking place on the shaded side of the street.

The Korean grocery store and Sal’s pizzeria were built from scratch on two empty lots. The pizzeria was fully functional and the actors actually cooked pizzas in the ovens.

During filming, the neighbourhood’s crack dealers threatened the crew for disrupting their business, leading Lee to hire members of the Fruit of Islam – part of the Nation of Islam – to provide security.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37