Following the death of Nicolas Roeg earlier this month, RICHARD LUCK pays tribute to a filmmaker who forwent the traditional formulas of cinema

‘Somebody I never met but in a way I know/Didn’t think that you could get so much from a picture show.’

Those are the opening lines of Big Audio Dynamite’s E=MC2, perhaps the only rock song ever written about a movie director. It’s rather fitting that the filmmaker in question, the late Nicolas Roeg, should have been celebrated in such a fashion, what with his having coaxed several great performance from musicians. Mick Jagger (Performance), David Bowie (The Man Who Fell To Earth), Art Garfunkel (Bad Timing) – all were at their best under Roeg’s direction.

As the lyric is a neat summary of Roeg’s work and its impact, the aforementioned movies encapsulate the key themes of his cinema. Sex, death, identity, time, memory, violence – Roeg is by no means the only director to have been preoccupied with these topics, but no one else dealt with them in quite as complicated and uncomfortable a manner. It’s as fellow director Alex Cox said: ‘[Roeg’s] most interesting aspect… is the editorial: his films are structurally very complex and convoluted. Watching one is rather like watching six or seven televisions in a row, each of them transmitting a different story.’

Roeg’s own story began in Marylebone on August 15, 1928. Later claiming that he entered the film business because he lived directly opposite a studio, Nic worked his way up from tea boy to clapper loader before making a decent name for himself as a camera operator.

He was promoted to cinematographer in the early 1960s, gaining experience on B-pictures like Roger Corman’s The Masque Of The Red Death before graduating to more respectable fare, such as Francois Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451, John Schlesinger’s Far From The Madding Crowd and Richard Lester’s Petulia. On the strength of his second unit work on Lawrence Of Arabia, David Lean hired Roeg to lens Doctor Zhivago, only for the pair to fall out. Kicked off the picture, the director of photography was more aware than ever that the director’s chair is where the real power lies.

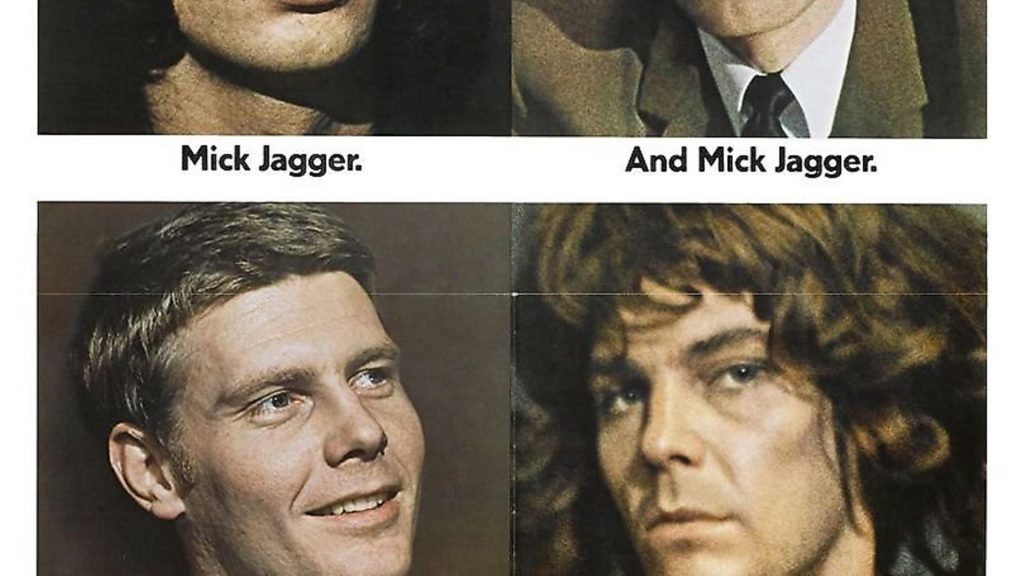

As befits a man with little respect for linear storytelling, Nic Roeg’s first film was almost his second. Shot in 1968, it would be two years before MGM dared show Performance to the general public. The tale of an East End gangster (James Fox, cast brilliantly against type) who seeks refuge in the Notting Hill abode of a retired rock star (Jagger), it was directed in collaboration with Donald Cammell, the heir to a Scottish shipping fortune and a man so extrovert, Mick Jagger seemed shy by comparison. The sort of chap who would have listed threesomes as one of his hobbies had Who’s Who ever bothered to ask, the ultimate good-time boy Cammell and the consummate professional Roeg conspired to make a film that championed androgynous sex and psychedelic drugs. Little wonder the movie execs loathed it; less wonder still that the kids lapped it up.

Though it might have damaged Cammell’s career (he’d only direct three further films before shooting himself in 1996), Performance and its attendant controversies couldn’t harm Roeg whose ‘second’ film was already good to go. Adapted from a novel by James Vance Marshall, Walkabout was a children’s film, albeit one with two suicides and a lot of full-frontal nudity.

In spite of this, the picture is every bit as poetic as the AE Housman stanzas which provide its closing lines:

‘Into my heart an air that kills, From yon far country blows. What are those blue remembered hills, What spires, what farms are those?’

Now off and running, Roeg entered the most prolific period of his career. Infamous for its ‘did they or didn’t they?’ sex scene, 1973’s Don’t Look Now is a shattering story of loss and regret that doubles as a top-notch slasher movie.

It is also the film that proved you could combine such disparate elements and still attract an audience. That The Man Who Fell To Earth was also a hit had an awful lot to do with its leading man. But those that came for Bowie left contemplating match cuts of nipples and mountain ranges, not to mention the sight of Candy Clark pissing herself upon discovering her boyfriend’s alien identity.

It would reveal a shocking lack of self-awareness were I not to acknowledge that this entire article could be dedicated to analysing Don’t Look Now, Man Who Fell To Earth, each of Roeg’s cinematic releases, in fact.

If mentioning brief snatches from his films has any worth it is because Roeg himself was obsessed with the moment and one’s changing memory of it. When 1980’s Bad Timing screened on BBC 2’s Moviedrome, curator Mark Cousins recounted the story of Roeg watching a film being dubbed into French, falling in love with ‘the way the action went forward and back, forward and back until the actor got the timing right. He said that this made him think of cinema as a kind of time machine, and it seems to have drawn his attention to the pleasures of fragmented bits of action, of moments intensified by repetition’. Cousins also remarked on the need to revisit Roeg’s movies to appreciate their emotional complexity. This is particularly true of Bad Timing, a film where love is portrayed not as a reason for living but as a destructive force capable of exterminating life.

Such was the intensity and ‘otherness’ of his films, one might imagine that, as Moviedrome presenter Alex Cox put it, Roeg was ‘one of those reclusive geniuses who only makes a great work once every seven years’. In reality, a warm, affable man, Nic was a prolific filmmaker, directing five features over the course of the 1980s. With Eureka (1983), he told of a gold prospector who unearths a fortune, and that is only the beginning of his troubles. (‘Once I had it all,’ sighs Gene Hackman’s millionaire. ‘Now I just have everything.’) With 1985’s Insignificance, Roeg successfully adapted Terry Johnson’s theatrical study of celebrity and science, directing Tony Curtis to his last great film performance into the bargain.

A year later, he brought forth a great turn from Oliver Reed as Gerald Kingsland, the ageing eccentric who seeks to make a success of island life in Castaway. Both that film and 1987’s utterly incomprehensible Track 29 were produced by Rick McCallum, now better known as a key George Lucas collaborator.

‘We were filming Track 29 in North Carolina and we started chatting about whether the movie would be successful,’ McCallum told me, in 2003. ‘I said that with a cast like we had – Gary Oldman, Christopher Lloyd, [Roeg’s then wife] Theresa Russell – we might have a hit on our hands. ‘Ah, dear boy,’ whispered Nic, ‘you can never know such a thing. Sometimes with a film, you have to lock it away for a few years like a wine, and hope that it matures. And sometimes, you have to lock away a film and make sure it never escapes.’ I think there’s real wisdom there.’

Roeg’s own ‘lock ’em up’ period came on the heels of his biggest hit, 1990’s The Witches – to this day the finest big-screen adaptation of Roald Dahl’s work – and a big disappointment, 1991’s Cold Heaven, the release of which was compromised by the production company going bankrupt. With work low on the ground and the bills mounting up, the cinematic visionary was reduced to accepting offers of television work. A Young Indiana Jones Chronicle here, a telemovie there – it was well beneath the man who’d transformed James Fox into a Ronnie Kray-alike and that nice Arthur Garfunkel into a necrophiliac.

Those films he did make during this era – principally 1995’s Two Deaths and 2007’s Puffball, his final picture – weren’t without their merits but they were distinctly minor Roeg.

The same could not be said of his autobiography, The World Is Ever Changing – a dazzling memoir light on ‘a funny thing happened on the way to the film set’ anecdote but invaluable to understanding the author’s fascination with magic realism, dream logic and synchronicity. Given this love of coincidence, Roeg might have found some humour in his dying the same month that a landmark book on his debut picture is published. And since Performance: The Making Of A Classic is a definitive work, it’s only fitting that the final word on Roeg should go to its author Jay Glennie:

‘One of the first things Nic said to me was to apologise for his ‘grasshopper mind’. Any thoughts of a conventional interview were quickly dispelled. I was diving into the world of Nic Roeg and I was instantly seduced. Just like his films, Nic’s thought patterns were nonlinear, each answer sent me free to explore new and different possibilities.

‘My deep regret is that Nic never lived to see our Performance 50th anniversary book. Harriett, Nic’s lovely wife, told me that she had shown him some of the articles and Nic had enjoyed seeing Performance find a whole new audience. I am forever in his debt for allowing me to experience his warmth.’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37