A century on from his execution, Roger Casement remains a complex and intriguing figure. BENJAMIN IVRY reports on the latest attempts by historians and writers to get to grips with him.

In February 1965, as the Dead March from Handel’s oratorio Saul played, an army escort and dignitaries ceremonially paraded the remains of Roger Casement through the streets of Dublin. The ultimate destination was Glasnevin Cemetery, where Michael Collins and other Irish nationalist leaders repose. A half-century after he was buried in the grounds of Pentonville prison, following his execution there for high treason, Casement’s remains had been belatedly delivered to the Republic of Ireland by Britain.

How Casement (1864-1916), a diplomat, Irish nationalist, and humanitarian, evolved from an honoured part of the UK establishment to firebrand sentenced to death is one of the most significant political metamorphoses in recent European history. And a century on from his death, the man himself remains an enigmatic, complex figure – still the source of debate and fascination for historians and writers.

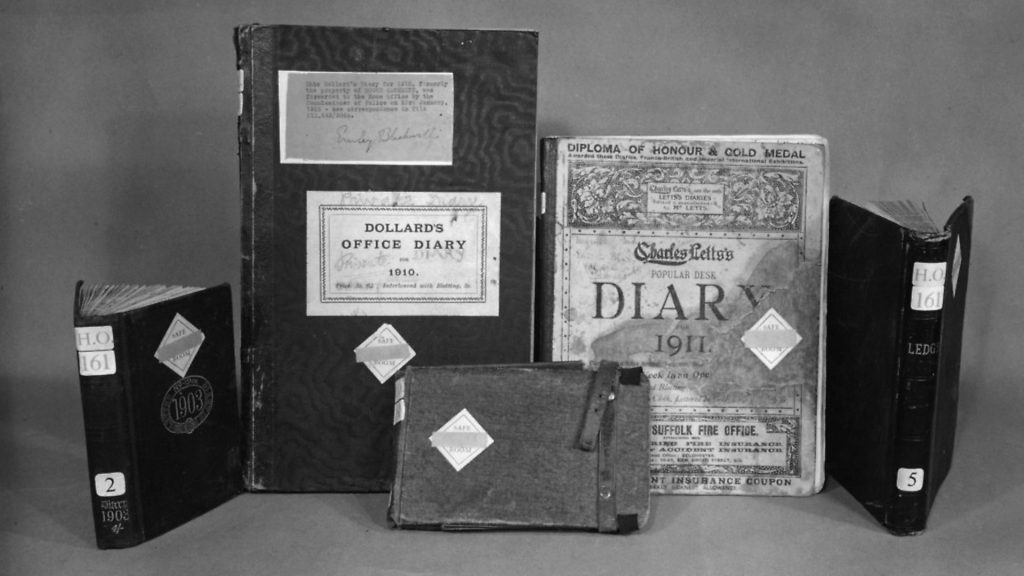

Working for the Foreign Office as a diplomat, Casement was a prolix scribe, dashing off thousands of words daily. These most famously included reports on the human rights abuses in what was then the Belgian Congo. In 1903, the British government had commissioned Casement, serving as consul at in the Congo Free State, to investigate the colony of Leopold II, King of the Belgians. In his report the following year, Casement declared, he had witnessed “enslavement, mutilation, and torture of natives on the rubber plantations”. A year later, an independent commission of inquiry reached the same conclusion as Casement had, and before long the Belgian parliament had assumed oversight of the Congo Free State, diminishing abuses.

Casement was honoured for his work by being appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George, the British order of chivalry, in 1905. He would be knighted for his next major project, to investigate slavery by the Peruvian Amazon Company, another result of colonial rubber industry.

In the Amazon Basin, which Casement visited in 1910, he wrote: “Whole families… were imprisoned – fathers, mothers, and children, and many cases were reported of parents dying thus, either from starvation or from wounds caused by flogging, while their offspring were attached alongside of them to watch in misery themselves the dying agonies of their parents.”

Recognised and appreciated by the British establishment as a human rights campaigner, Casement understood such abuses to be part of imperialism and colonial role. The roots for his future conclusions were established early. Even as a youth, Casement was an adherent of Charles Stewart Parnell’s advocacy of home rule for Ireland, as a 2008 biography by Séamas Ó Síocháin asserts.

After retiring from the British consular service in the 1913, Casement helped to form the Irish Volunteers, a military organisation founded by nationalists to “secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland”.

In 1914, when the First World War broke out, Casement made efforts to persuade German forces to sell guns to Irish revolutionaries. It was hoped that this would lead to a rebellion against English rule. Casement’s efforts would lead to his downfall. Travelling with weapons from the Kaiser to better launch what would become the Easter Rising of 1916, Casement was arrested on the southwest coast of Ireland, after landing in a German submarine. He was tried for treason, despite his protest that as an Irishman, he owed no loyalty to Britain.

At this point, his private life, which should have been irrelevant, was made semi-public. The British government used some private diaries kept by Casement, summary recordings of sexual encounters with men in different countries, to dissuade any popular defence against his sentence of execution. Just two decades after Oscar Wilde had emerged from imprisonment, such accusations were lethal, as the government well knew.

To this day, the use of these private writings in sealing Casement’s death sentence stir such emotions in Ireland that a minority of writers and readers still claim that they are forgeries, despite authoritative scientific and historical studies deeming them authentic. Séamus O Síocháin refutes the nay-sayers, euphemistically terming their arguments “tendentious”.

Prejudicially, the journals were termed Black Diaries on the occasion of a partial publication in 1959 by Maurice Girodias, a Paris-based purveyor of smut and the occasional literary masterpiece considered too racy for standard issuance. It is well past time for giving these texts to a more objective title. They are not black, but merely concise notations of longing and exultation by a man cast into unfamiliar lands with the income to pay for companionship.

The question emerges whether Ireland and the wider world is willing to accept a Casement who, in addition to his heroic national status, was also a human being with erotic foibles.

Given the inherent drama in the subject matter, Casement’s story has appealed to novelists. In 2010, the Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize for literature, produced a novel The Dream of the Celt (El sueño del celta). Translated into English two years later, it received mixed reviews. Colm Tóibín complained in the London Review of Books: “In most of [Vargas Llosa’s] narrative, Casement is not only simplified, which any novelist has a right to do with a figure from history, but he is simple, not of much interest – which is a different matter.”

Vargas Llosa was certainly moved by the human rights violations by the Peruvian Amazon Company as exposed by Casement, but could not for all that bring the latter to life as a character.

With a Nobel Prize-winning novelist thus baffled by the challenge of fictionalizing Casement’s experience, how did a veteran American historian fare? Luminous Traitor: The Just and Daring Life of Roger Casement, a new novel by the American historian Martin Duberman, explores the Irish nationalist’s human rights ideals and his controversial sexual expression.

Duberman himself has campaigned for social issues, and published a life of the African American singer and activist Paul Robeson. Luminous Traitor is offered as a biographical novel, but it is more fantasised history, with expository material interspersed by imagined discussions.

A recent review of Luminous Traitor in the Irish Examiner scorns its “inaccuracies”, yet if anything it is too close to history to satisfy as a novel. Narrated in a donnish tone that sometimes sounds all-too-omniscient, Luminous Traitor concedes that “there’s a mild obsessive-compulsive thread in Roger’s personality,” a Yankee understatement if ever there was one.

At the most dramatic moment of the narrative, Casement’s execution, Luminous Traitor bafflingly recuses itself. Casement’s hanging is noted only from a distance:

“A crowd has gathered outside the prison walls. At a few minutes past nine, the bell sounds, signalling that the execution is completed.”

Casement the man remains elusive, best glimpsed in a Hearst International Film Pictorial Newsreel filmed in Berlin in 1915 and posted online. Now in the collection of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, it is tantalizingly brief, just over half a minute, and silent. Thin to the point of emaciation, Casement is shown writing letters – not in his private diary, to be sure.

He appears nervous, plucking at his face, and makes rather theatrical gestures in folding papers, possibly for the benefit of the camera operator. A further shot of him smoking a cigarette is mainly noteworthy for his extremely mobile face, with fleeting expressions and glowing eyes.

He is anything but a stolid government inspector. Instead, he appears to be alert and attentive to each new moment, ideal for someone who sought out fleeting, spontaneous contacts with others in foreign lands.

That Casement’s private life became public was an accident of history. No accident was his development from a decorated British civil servant into an Irish nationalist willing to die for his cause.

Surely it is time to get past the distraction of Casement’s private diaries, to better appreciate perhaps his most remarkable achievement, his evolution from imperialist to revolutionary.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37