2017 marks the centenary of the Russian Revolution. The Soviet Union which emerged from it may be in the dustbin of history, but we are still living in the long shadow of the events of 1917

The Polish-born political activist, Isaac Deutscher once subtly asserted that ‘each great revolution begins with a phenomenal outburst of popular energy, impatience, anger and hope. Each ends in the weariness, exhaustion, and disillusionment of the revolutionary people.’

That certainly is the story of most revolutions that erupted over the last one hundred years, not least, in recent years, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the Arab Spring. Both ended in chaos, turmoil and violent civil war.

This year we are marking the centenary of one of the most defining revolutions of human history – that seen in Russia, in 1917. The subsequent birth of the Soviet state, the first real manifestation of Marxist ideas, provided a crucial point of reference for the global communist movement in its struggle against capitalism and imperialism throughout the twentieth century. Yet, even after its collapse in 1991, the revolution still casts a long shadow over the world we live in, no more so than in contemporary Russia.

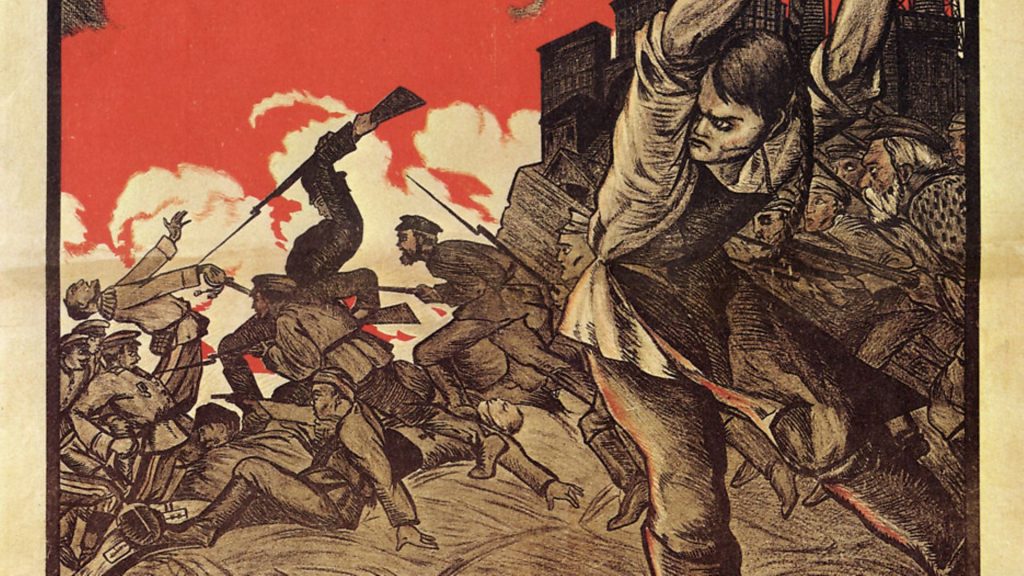

The Russian Revolution has been rightly called a peoples’ tragedy. It is a fascinating and moving tale of high hopes, ideals and dreams of human progress, many of which were sacrificed in the pursuit of winning power and holding it.

Furthermore, it demonstrates the remarkable ability of people to radically transform their socio-economic environment and even human behaviour itself. Ever since the start of the revolution – which in fact included two separate revolutions, one in February that overthrew the Romanov Dynasty, and one in October that ultimately brought the Bolsheviks to power – its history has been vigorously contested.

During the Cold War we witnessed the strange convergence of both ‘left wing’ and ‘right wing’ presentations, in both of which the ‘great man’ took centre stage. The former depicted the victorious march of abstract social forces under the leadership of the political genius, Vladimir I. Lenin; the latter portrayed the Bolshevik leaders, Lenin, Stalin and co. as all powerful manipulators of the masses and dictators-in-waiting.

Indeed, a quick look at the shelves of bookstores in the UK will reveals that this is still very much the popular prism through which we see Russia – Lenin’s Russia, Stalin’s Russia, all the way to Putin’s Russia. Yet, as so often, the reality was more complicated. The revolution had many different actors and numerous twists and turns.

Arguably, ever since the failed 1905 revolution that had nonetheless compelled Tsar Nicholas II to introduce a parliament, the State Duma, the tsarist regime was on borrowed time. The tsar had managed to reassert his authority. However, his holy image as the caring ‘little father’ of the Russian people had been irrevocably damaged when his guards opened fire at peaceful protesters in St Petersburg in January 1905. Moreover, in spite of its ultimate failure, the revolution had spurred ordinary people to engage in open protest for the very first time. The genie was out of the bottle – mass politics had arrived in the empire.

The tsar, though, refused to adjust to the new realities. Nicholas’ inability and stubborn unwillingness to adapt, and his determination to preserve the traditional autocracy led to growing social fragmentation and tensions. His regime was set on a collision course, not only with the growing urban working class but also with an emerging civil society. In many respects, the outbreak of the First World War provided the tsar with some breathing space, because citizens rallied behind the war effort. However, the conflict placed tremendous strains on all the belligerents and ultimately unleashed its disintegrating force. Within a few years it destroyed not only the Russian, but also the Austro-Hungarian, German and Ottoman Empire.

Russia’s dismal performance during the war and Nicholas II’s decision personally take command of the army had left the autocratic regime in a precarious situation in winter 1916-17. The police in Petrograd – a renamed St Petersburg – was alarmed that a revolutionary situation was in the making. All sections of society, its reports asserted, had awoken and were openly expressing their discontent with the regime.

The Duma, too, was by now in open revolt. Pavel Miliukov, leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party and member of the Progressive bloc – an alliance of parties forged to help organise a more effective war management – openly mocked the tsar. Attacking his leadership, he asked his fellow Duma members: ‘Is this stupidity or is it treason?’ As the voices for a real accountable government grew stronger, for many observers it was not so much a question as to whether a revolution would occur, but when and what form it would take?

In the end, it began in the bread queues of Petrograd on International Women’s Day, February 23, 1917 (by the calendar in use at the time). The food supply situation had deteriorated dramatically and women began marching towards the city centre. As they were joined by young and old metal workers, the demands quickly went beyond just bread. The slogans ‘Down with the tsar!’ and ‘Peace, Bread, and Land’, resounded. As days passed, the crowds grew. This was a genuine popular revolution, in which political parties played no prominent role – indeed, the senior Bolshevik leaders observed the outbreak of the February revolution from the coffee houses of Switzerland.

Within a few days, Petrograd was fully in the grip of a general strike. Significantly, this time the Cossacks proved unwilling to reassert order by shooting at demonstrators. It was the crucial difference with 1905. Nicholas had lost the support of sections of his army. And when mutinies started to break out in the capital’s garrison and soldiers openly fraternised with the demonstrators, the regime’s fate sealed.

After more than three hundred years, the Romanov dynasty, which had proved so successful in suppressing discontent, collapsed overnight without so much as a whimper. While Nicholas raged that ‘all around is betrayal, cowardice and deceit!’, he was powerless to prevent the disintegration of autocracy. On March 2, the military high command left him no other option than to abdicate. The same day a Provisional Government was formed to restore order and prevent the country from sinking into anarchy.

Almost overnight Russia became, as Lenin put it, the ‘freest country in the world’. The Russian people obtained fundamental democratic rights, freedom of speech, to assemble and demonstrate. Universal adult suffrage was introduced, giving all Russian women the right to vote, more than a decade before that equal right was granted in the UK. Yet, despite these popular policies, the Provisional Government struggled to impose its authority not only in Moscow and Petrograd, but particularly over the periphery of the country.

New revolutionary organisations, such as the Soviets, factory committees, and a myriad of public committees were mushrooming across the empire, revealing and deepening the social fragmentation and polarisation. Not surprisingly, the competing interests of different social groups led to a diffusion of political power and contributed to a general crisis of authority in the country. Furthermore, the triumph of the liberals in the February Revolution had turned them immediately into the new conservatives in the new political landscape.

Some moderate socialist parties joined the Provisional Government in May 1917, but in spite of their input it proved to be impossible to respond adequately to the calls for far-reaching reforms amid fighting an ever more unpopular war. The government’s lack of a real democratic mandate meant that many reforms were postponed until after the election of a Constituent Assembly scheduled for later in 1917.

If, for example, the Provisional Government had decided to start implementing a land reform in summer 1917, this would have undoubtedly led to a further disintegration of the Russian army. Peasant conscripts would have deserted in even higher numbers and rushed back home in order to not lose out. Furthermore, a major problem for the new rulers was that their actions and inactions began to be measured against the demands of a party with the most radical programme for revolutionary transformation – the Bolsheviks.

With Lenin’s return to Russia in April 1917, the Bolshevik Party adopted an uncompromising and belligerent radical programme of non-cooperation with the new rulers. It also demanded an immediate end to the war, positioning itself distinctly against the Provisional Government’s policy that saw Russia keep fighting a defensive war.

However, in April they were still a small minority party. And while they were more united than the other socialist parties, the myth of a centralised Bolshevik party of professional revolutionaries has long been debunked by historians. In its path to power, the Bolsheviks would benefit from many mistakes and miscalculations by the Provisional Government, such as the ill-conceived June military offensive against the Germans. Bolshevik propaganda and agitation played a crucial role in the growing radicalisation of the masses, but the party was not the primary cause for popular discontent in 1917. This stemmed from by the continuing economic deterioration, rising inflation, increasing unemployment, and real hunger in the country.

As the Provisional Government failed to get a grip on the economic situation in summer 1917, workers increasingly turned towards the Bolsheviks who appeared to represent the only viable alternative. Indeed, the party proved adept at exploiting many popular slogans of the street demonstration in their political programme, such as workers’ control of factories, ‘Peace, Bread, and Land’ and, most critically, ‘All Power to the Soviets’.

What happened during those summer months, then, was a growing correspondence between workers’ aspirations and the political programme of the Bolsheviks. As a result, the party’s ranks were flooded with new members and its activists, not surprisingly, began to be voted into leading positions of power in many local Soviets and factory committees.

Indeed, many of the mass organisations created by the revolution began to adopt Bolshevik positions even before the party was in control of them. The reasons for this was a general shift to the political left, which saw several more moderate socialist parties split. The Bolsheviks, thus clearly began to gain political capital from developments that were not of their own making. One such development came at the end of August, when the Provisional Government had to rely on Soviet military support to stop an attempted coup d’état by the then commander-in-chief of the Russian Army, General Kornilov. The subsequent complete loss of confidence in the Provisional Government led workers and soldiers to look for more radical solutions. The most important Soviets in the country began to adopt resolutions sponsored by the Bolsheviks demanding a transfer of power to the Soviets. Meanwhile, such demands had gained the wide support of various sections of the population.

As autumn loomed, just as a year earlier, it was not so much a question whether Russia’s government would fall, but when and how? Leading Bolsheviks began to vigorously debate the question. Interestingly, it was not Lenin who won the argument, but Leon Trotsky, who successfully argued that, in spite of their growing popularity, the masses would not come out in support of a Bolshevik coup d’état. Power, he asserted, must be taken in the name of the Soviets and appear as a defensive action, a response to an attack against the left.

Historical chance was once again on the side of the Bolsheviks. Just before the Second All-Russian Congress of the Soviets was set to open, the Provisional Government’s decision to close down the Bolshevik newspapers on the October 24 gave them the ‘counterrevolutionary’ action they needed in order to mobilise their forces.

There was little actual fighting in Petrograd during the ‘October Revolution’. Most inhabitants were entirely unaware of the momentous events that were unfolding. Crucially, the garrisons of the capital proved to be either supportive of the Bolsheviks or indifferent. As a result, the leader of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky, just like the tsar a few month earlier, struggled to organise any significant military support. Thus, his fate was sealed, and the struggle moved quickly to the political arena of the Congress of the Soviets.

Many people had expected a transfer of power to the Soviets to be declared at the congress. An all-socialist coalition government answerable to the Soviets would have enjoyed widespread support from vast sections of the population. However, Lenin was not keen to share power. When the main socialist opponents, the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, walked out of the congress in protest against the Bolsheviks’ overthrow of the Provisional Government, they handed them the power on a plate. Off they went, as Trotsky famously said, ‘into the dustbin of history’.

The October Revolution, thus, was something between a popular revolution and a swiftly executed coup d’état. It was the political solution to a long-drawn out social crisis which had led to rapidly growing support for Soviet power. Taking power had been relatively easy for the Bolsheviks. Indeed, there was no significant protest against their actions on the streets of the capital. Yet, they still faced several, arguably much bigger, challenges – to turn ‘Soviet power’ into Bolshevik power and spread it beyond the boundaries of the capital.

Over the next few days, the newly established Bolshevik government immediately began to announce an ambitious programme of reforms, issuing decrees on land reform, workers’ control, and Russia’s withdrawal from the war. These were hugely popular actions, but for the Bolsheviks they were seen only as the beginning of an ideologically driven global process of constructing socialism and creating a new Soviet person – an ambitious and utopian agenda shared only by a minority of the population.

This became clear in the elections to the Constituent Assembly, preparation for which had been well under way in autumn 1917. The results demonstrated the widespread popular support for a multi-party socialist system and a parliamentary republic with a government answerable to the Soviets. Well over two-thirds of the votes went to Socialist parties, with the Socialist Revolutionary party, the party most familiar to the peasantry, winning the elections with more than 40% of the share.

The Bolsheviks, in turn, had overwhelming support amongst the workers and soldiers. Having already taken power, Lenin had no intention of compromising either on the principle of ‘Soviet power’ or his plans to pull Russia out of the ‘imperialist’ war. Firmly believing his party was enacting the law of history, the first act of a world socialist revolution, he decided to forcefully disperse of the Constituent Assembly in early January 1918. In doing so, Lenin effectively chose Civil War. From that moment onwards his government could not any longer be challenged through political institutions. Any opponent of Bolshevik rule was forced to take up arms.

Between January 1918 and March 1921, the disintegrating empire was ravaged by a series of bloody civil wars, not just Reds versus White, but involving moderate Socialists, peasant rebellions and nationalist uprisings. The war had immense human costs. An estimated seven million died, most of them as a result of famine. The Bolsheviks ultimately emerged victorious, but the fact that they had started to build their new system amid war profoundly shaped the nature of the new Soviet state. They constructed it on centralised, militarised and coercive lines.

The country entered a vicious spiral of escalating violence as the new ruler resorted to increasingly authoritarian measures to consolidate their grip on power. Fearing counterrevolutionary everywhere, the creation of the Secret Police, the infamous Cheka, in December 1917, established a crucial instrument to assert power under the new regime. Violent repression of opponents became the norm rather than the exception.

Nonetheless, there was no direct path from Lenin to Stalin. Indeed, the 1920s became a period of unprecedented revolutionary experimentalism, flourishing cultural production, and some extraordinarily progressive legislation on issues such as marriage and abortion. Yet, this decade of qualified freedom under one-party dictatorship was short-lived. The political structures and social conditions that made the excessive use of state violence under Stalin possible, were present from the earliest days of the Soviet experiment: the extreme centralisation of power, close censorship of media, excessive police power, and a brutalised political culture.

And of course, there was the Bolshevik leadership’s sectarian arrogance and preparedness to sacrifice human lives in pursuit of building a new world. The result was one the most traumatic, tragic social upheavals that history has seen.

The Russian Revolution produced a system of paradoxes – a political regime that would provide an extensive welfare state to its citizens; unleash social mobility that allowed a child of poor peasants, like Nikita Khrushchev, to climb all the way up to the top; one that would create an administrative-command economy and military complex which would enable the Soviet Union to defeat Nazism and later beat the Americans in the space race. Yet, a political regime that also created the Gulag and would terrorise, imprison and kill millions of its own population in the name of constructing communism.

This is the difficult, complex, and harrowing legacy of 1917, which has left deep marks on the Russian soul. It is a legacy that makes it a real challenge for the current Russian government to decide how to mark the centenary, not least because many current problems have their roots in the Soviet era and the year 1917.

Revolutions are a dangerous business. The last thing the Putin government would want to happen is for the centenary to inspire ordinary Russians to take their grievances to the streets. Yet, in recent days, significant demonstrations have broken out in Moscow and St Petersburg against the rampant corruption at the heart of the political class in Putin’s Russia and the continuing economic downturn.

Over the last few years, Russians have started to feel the consequences of the growing economic crisis. And as a result, it becomes more difficult for the government to rally the population through a bizarre marriage of ethnic Russian nationalism with Soviet superpower nostalgia – most vividly demonstrated in the annexation of Crimea in 2014. The latter saw Putin approval rates reach new heights.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe’ of the 20th century according to Putin, Russia failed to fundamentally democratise its political structures. The gangster capitalism of the Yeltsin years produced huge social inequality in the country. It left millions of Russians impoverished, making them long for the Soviet welfare state.

At the same time, the new Russia allowed a selected few, many of whom were and are members of the political elite, to acquire incredible wealth, much of which has since been ‘washed’ in London real estate.

The overall result of this unfinished transition from the Soviet system to democracy was a system that is subject to a persistent conflict and imbalance between the administrative regime and its constitutional state apparatus. ‘Russia under Putin has in fact regressed and become increasingly authoritarian again. Putin calls it ‘managed democracy’ – managed by him, from the Kremlin, where real power still rests.’

While it is currently difficult to see the recent protests experiencing a different fate to those of the last wave in 2010-2013, they are visible evidence of cracks in the fabric of the system. In this context, the Russian Revolution serves as a poignant reminder – to us as well as the man in the Kremlin – that even a regime capable of absorbing and suppressing discontent for several centuries can be swept away by the power of the people.

Indeed, as a child of the 1989 revolution in East Germany, I vividly remember the empowerment and escalating ambition of street protest in the face of a seemingly all-powerful state. Protests can quickly develop their own dynamic and momentum. And that is the worrying reality for the Russian government, and the reason it denies people official permission for demonstrations, enforces a media blackout when unsanctioned street protests do take place, and employs the iron fist of OMON, a special police force, to break up gatherings whenever they manifest.

Against this backdrop, then, it will become even more fascinating to see how the Russian state will face the dilemma of having to mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution this year.

Boris Kolonitskii, one of the most eminent Russian scholars on 1917, recently remarked that the Russian state is likely to adopt a theme of ‘national reconciliation’ in its commemorations. We must wait and see how far the Putin government will succeed in squaring the circle in its pursuit to construct a coherent national history that bridges the deep 1917 divide.

Until then, interested readers should follow the excellent Russian project www.project1917.com, which allows us to relive the events of 1917 day by day through the eyes of those who lived through one of the defining moments of twentieth century history.

Matthias Neumann is a senior lecturer in Modern History at the University of East Anglia and an expert on the history of the communist youth movement

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37