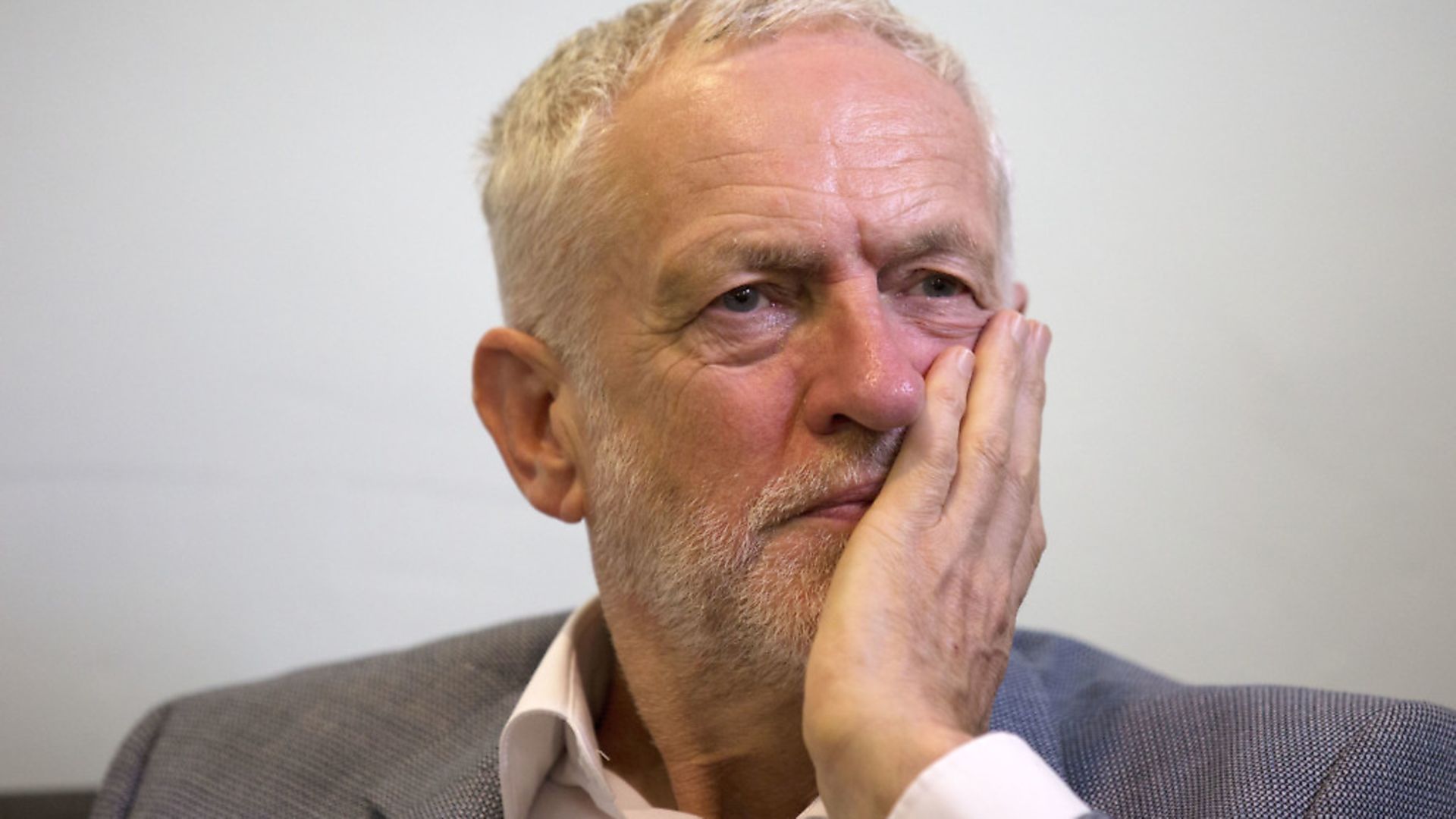

The electoral logic is inescapable, and even Corbyn will soon grasp it… Labour must support a People’s Vote, says historian of the Labour movement FRANCIS BECKETT

iframe width='100%' height='300' style='background-color:transparent; display:block; padding: 0; max-width:700px;' frameborder='0' allowtransparency='allowtransparency' scrolling='no' src='//embeds.audioboom.com/posts/6982312-best-for-britain-raabbiting-on-and-donald-trumped/embed/v4?eid=AQAAAC3ofluoimoA' title='Audioboom player'>

This Saturday, the leaders of Momentum will meet to make a decision which will have far-reaching consequences for the fortunes of the man it was established to bolster, Jeremy Corbyn, and for the country.

They will consider a petition, signed by more than 4,000 members, urging the organisation to canvas opinion in its ranks on whether to call for a vote at the Labour conference on support for a People’s Vote. Should the organisation shift its position on Brexit in this way, it could trigger a chain of events that would unravel the entire process and leave Britain still in the EU. In this, as in much else, Momentum will be operating as Corbyn’s vanguard.

For committing Labour to a second referendum is both in line with Corbyn’s principles, and the best pragmatic move he can make. After studying the Corbyn phenomenon for a new book, I’ve come to the conclusion that he is starting to realise this – but perhaps too slowly.

Back in 1975, when Britain voted to join what was then called the European Community, the left opposed it because they thought it was a capitalist club. When a radical Labour government took power in Britain, it would find its plans for nationalisation, for greater right for workers and trade unions, for a more equal and a more socialist society, stymied by the unelected bureaucrats of Brussels.

That was the view articulated by Tony Benn, and supported by an unknown foot-soldier of the left called Jeremy Corbyn, who that year started a new job as an organiser for the National Union of Public Employees.

Just four years after the referendum, the Labour government fell, and Margaret Thatcher started to roll back its modest advances. The socialist society was going to have to wait, Europe or no Europe.

It was not until 1997 that we saw another Labour government. The moment it was elected, prime minister Tony Blair set about with a will to prevent the European Commission from issuing a directive which would require employers to inform and consult trade union representatives when closures were contemplated.

John Monks, then general secretary of the TUC, told me: ‘Britain went to war to block the directive.’ Four countries were required to block it, and there were only three, including Britain. So the Blair government set itself to recruit a fourth – Germany. But in Germany, trade unions already had these rights, and German employers did not see why other employers should not have to operate under the same constraints as themselves.

So Peter Mandelson was sent to Germany as Blair’s emissary to tell chancellor Helmut Kohl how important the British government thought it was to block the directive. At last, and only as a favour to the British, Kohl and the German employers’ organisation agreed to change their stance.

Britain’s Labour government also led opposition to the proposed directive which would give agency workers the same rights as permanent workers. Some employers were using agency staff as a way of avoiding employment legislation, because if an employee was classified as an agency worker, he or she could be fired at a moment’s notice, with no explanation.

‘The British government blocked that ferociously’ Monks said. ‘We would have it without the British government.’ Later there was the working time directive, which said that normally no one should work more than 48 hours a week, and that if they did it should be part of a collective agreement. European social democrats, and even Christian Democrats, were amazed at how determined Britain was to block it.

The idea of British workers’ rights being held back by reactionary Brussels bureaucrats, which seemed reasonable in 1975, was clearly absurd by 1997. And it is no more sustainable now, in 2018.

Suppose Corbyn were to become Prime Minister tomorrow. His programme, stripped of the hyperbole of both his friends and his enemies, is a pretty moderate, mainstream one. Is Europe really going to block – say – rail renationalisation, when France is one of several EU countries whose railways are state owned? Is it going to block the rather modest rights for workers which many EU countries already have, and which Britain had when it entered Europe?

But – Labour’s few remaining Brexiteers will argue – will not Labour heartlands feel betrayed if the party goes for a second referendum? Many of its traditional supporters voted for Brexit and expect it to be delivered. Supporting a second referendum, runs the argument, will therefore be electoral suicide.

It’s true that about a third of Labour voters voted for Brexit, but the latest poll shows that 76% of Labour voters now think it was the wrong decision.

And it’s precisely the new, young, idealistic voters brought into the Labour party by the Corbyn phenomenon who are keenest on getting a second referendum. Corbyn does not depend on what we used to call ‘Labour heartlands’ – or, at least, he depends on them less than any of his predecessors. The class analysis on which the Attlee settlement was built no longer applies, or does not apply in the same way. For something very odd is going on with Britain’s political arithmetic.

That was suddenly very clear in the 2018 local elections. At first sight they seemed to show little major change – a slight shift to Labour from the general election, but nothing spectacular.

But if you look at them closely, they show something very odd and entirely new. Labour is losing votes in some white working class areas, and making major and spectacular gains in some of the most affluent areas that stayed Tory even under Tony Blair. I owe this analysis to the investigative journalist David Hencke, who put it on his blog. In affluent Tory Westminster, Labour gained four seats overall and narrowed the gap between Labour and Tory across the borough to 1.8%. It took one of three seats in the West End ward – covering Mayfair, Soho and Fitzrovia in central London.

As Hencke put it: ‘Oxford Circus, Park Lane, Bond Street, Grosvenor Square, the Dorchester hotel, Savile Row, Regents Street and the editorial offices of Private Eye are now represented by a Labour councillor. Since the ward was created in 1978 Labour has never been in sniffing distance.’

In Harrow, north London, where Labour increased its majority to seven over the Tories, Labour took Harrow on the Hill – one of the poshest bits of the borough, and the one that includes Harrow School and a private hospital.

Labour did amazingly well in the affluent seaside town of Worthing, which many well-to-do people retire to, and which had not had a Labour councillor since 1966. In 2017 Labour won a seat in a by-election in the centre of the town. In 2018 it won another four council seats and came close in a number of others.

Yet in the traditionally Labour town of Nuneaton, the party lost eight seats – some by big margins. Nuneaton is 88.9% white British with a large proportion of pensioners. Immigration hardly exists – the biggest group are Poles – but it had strong support for UKIP, which has transferred to the Tories. It is overwhelmingly Christian, with just 12 Jews and 2,895 Muslims out of 126,000 people. Nearly two thirds of the population are working class – classified as C2, D or E.

Labour is gaining votes in areas that Tony Blair could not even dream about but losing votes in traditional English working class areas. The class nature of Labour England is crumbling. The new Labour England will look very different from the old.

This is part of the Corbynite harvest. These are Labour’s new voters, the young, the idealistic, the generation that feels betrayed, the people who used to believe that there was little point in voting because all the parties were all the same. These are the people who made Corbyn Labour leader and then enabled him to deprive Theresa May of her parliamentary majority.

And they are, overwhelmingly, Remainers. The bitter disillusion with the political class, which decayed into a sort of sullen nationalism which is at times indistinguishable from racism, and which gave us Brexit, does not touch most of them.

These are the people who expect Corbyn to listen to them, and if he does not, sooner or later they will become disillusioned with him too. They will see him as just another politician. And that will be the end of Corbyn and Corbynism, and of much more besides. It will be the end of hope for at least another generation.

Supporting a second referendum is also the only way the Labour leader has a hope of toppling Theresa May’s government, which is his first duty, for it is clearly incompetent and damaging. The only chance of toppling it is if a few pro-Europe Conservatives are brave and public-spirited enough to put a match to their political careers by helping the opposition to bring the government down. And why would they bother, unless they were clear they would get a second referendum?

I suspect Corbyn is inching towards support for a second referendum, but nothing like fast enough, for he is listening to the wrong voices.

Having come to the leadership because of the young and the new, he was at first, quite understandably, overawed by the responsibility. He never expected to lead his party, and he is a little frightened of the job. Of course he is; he’d be a fool if he wasn’t.

So he has gone for advice and protection, not to the young, unformed folk brought in by Momentum, but to the old sectarians, with their grim political certainties, some of them from the Unite trade union. Corbyn isn’t stupid, and he isn’t uncaring.

He has a shadow Brexit secretary, Keir Starmer, who is not only one of the cleverest people in politics, but has also cultivated a relationship of trust with his leader. Starmer can be relied upon to tell Corbyn that if he fails to commit to a second referendum, apart from doing serious damage to his country and his party, he will be hurting the people he has spent his political life championing, stabbing in the back those to whom he owes his leadership, and destroying any chance he has of ever rising higher than leader of the opposition.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37